Vouchers, which were abolished with Decree Law 25 of 17 March 2017 approved without amendment by the Chamber of Deputies, are a standardised mechanism for paying casual workers with facilitated tax and contribution treatment. This Focus (in Italian) analyses developments in the use of this instrument over time, the gradual expansion of its scope, and any impact it may have had in terms of transforming marginal activities or work normally performed informally into more regular employment. The Focus also examines similar mechanisms in other countries that could represent a benchmark for possible future measures in the areas of regularising casual employment.

The application of the voucher system – which was introduced in Italy in 2003 – was distinguished by a number of notable characteristics.

The first was the exponential growth in the use of the instrument in recent years.

The first was the exponential growth in the use of the instrument in recent years.

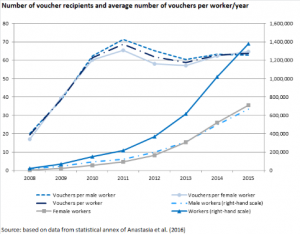

In 2008 about 536 thousand vouchers were sold, while in 2016 that number had soared to nearly 134 million. The annual rate of growth was more than 50 per cent until 2015 before slowing to the still rapid rate of 24 per cent in 2016. Recipients of vouchers rose from just under 25 thousand in 2008 to 1.38 million in 2016, with the growth almost equally divided between men and women. Despite the rapid expansion, at the end of the period examined, workers paid with vouchers represented no more than 5.6 per cent of total employees and self-employed workers, obviously with much fewer hours worked as well. These figures demonstrate that despite the rapid growth since 2008, the use of vouchers remains limited as a proportion of the overall labour market.

The second important development was the radical divergence in the use of vouchers from the purposes for which they were introduced (to foster the regularisation of irregular work in the informal economy, mainly performed by young people, pensioners or people with employment challenges working with households or social associations). Following numerous legislative changes beginning as early as 2005, this mechanism could be used without restrictions on the sector, the characteristics of the employers or the type of worker. The only constraints still in place in the most recent period were the ceiling on the annual remuneration allowed using vouchers and a number of limitations in agriculture and the tendering of works and services.

The second important development was the radical divergence in the use of vouchers from the purposes for which they were introduced (to foster the regularisation of irregular work in the informal economy, mainly performed by young people, pensioners or people with employment challenges working with households or social associations). Following numerous legislative changes beginning as early as 2005, this mechanism could be used without restrictions on the sector, the characteristics of the employers or the type of worker. The only constraints still in place in the most recent period were the ceiling on the annual remuneration allowed using vouchers and a number of limitations in agriculture and the tendering of works and services.

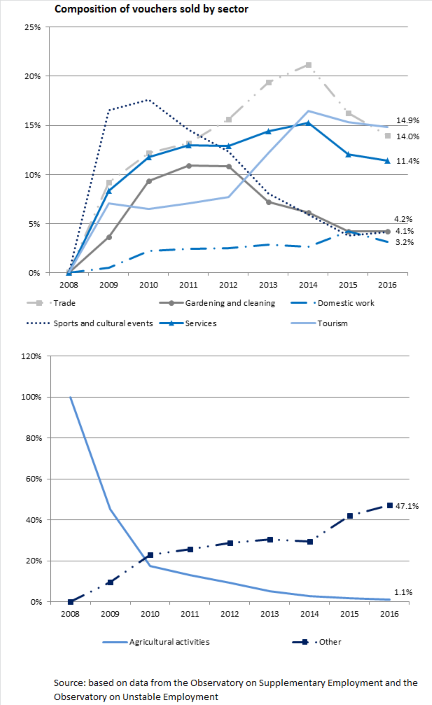

The impact of this shift was reflected in the mix of activities in which vouchers were used: agriculture saw its share of the total fall sharply (from nearly 100% in the initial years to 1.1 per cent in 2016), while the proportion rose in tourism (14.9 per cent in 2016), trade (14 per cent) and services (11.4 per cent). The sectors for which the voucher system was originally conceived ‑ in addition to agriculture ‑ such as domestic work, private tutoring, gardening and small-scale cleaning services, were marginalized.

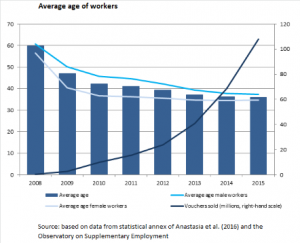

Legislative changes also modified the characteristics of voucher recipients: between 2008 and 2015, the average age declined by about 24 years, with greater involvement of the central age groups in the adult phase of employment.

Legislative changes also modified the characteristics of voucher recipients: between 2008 and 2015, the average age declined by about 24 years, with greater involvement of the central age groups in the adult phase of employment.

Thirdly, as regards the effects on the labour market, positive developments were flanked by negative developments, which gradually began to dominate with the progressive liberalisation of the scope of application of vouchers.

The positive developments included the possible reintegration of inactive people in the labour market and, to a lesser extent, the full regularisation of marginal occupations normally performed in the informal economy (for example, casual work by students and seasonal and irregular work in the agricultural and tourism industries). With regard to the former development, among those who received at least one voucher in 2015, more than 45 per cent were pensioners, “hidden” workers (i.e. those who in recent years have not paid contributions or received unemployment benefits or income support) and the “never active”.

The primary negative developments regard: the possibility that only part of the shadow economy is brought into the open, making it subsequently impossible to identify the part that has remained underground; the risk of increasing job insecurity for young people, who end up being employed with the voucher system rather than under more appropriate forms of contract; the replacement of existing employment relationships with voucher-based remuneration (in 2015 the proportion of people paid with vouchers by an employer with whom they had held a position as an employee or quasi-employee in the previous three or six months was 7.9 per cent and 10 per cent, respectively, with a particular concentration of such situations in tourism, services and trade). Finally, the absence of restrictions on the use of vouchers did not prevent a substantial share of workers from remaining in the voucher system for long periods. In 2015, the share of recipients who had already received vouchers in the past was 41 per cent, a significant increase on previous years (30 per cent in 2013 and 34 per cent in 2014). Of these, 22 per cent had used the mechanism for the first time the previous year and 19 per cent even earlier, and both percentages have increased recently.

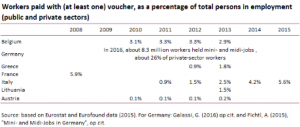

Finally, a comparison of the Italian case with the use of voucher systems in other European countries (Austria, Belgium, France, Greece, Lithuania) and mini-jobs and midi-jobs in Germany reveals a number of significant similarities and differences.

Finally, a comparison of the Italian case with the use of voucher systems in other European countries (Austria, Belgium, France, Greece, Lithuania) and mini-jobs and midi-jobs in Germany reveals a number of significant similarities and differences.

Observing the only information available for a comparison, i.e. the number of workers paid with vouchers or similar instruments and the number of people in employment (not taking account of the different number of hours worked), the use of vouchers in Italy is broadly in line with (or not excessively greater) than that in other countries with similar mechanisms. The proportion of mini-jobs and midi-jobs in Germany is substantially larger (more than 25 per cent of total private-sector workers in 2016). Nevertheless, the international comparison shines a light of a number of unique features of the Italian voucher system:

- the types of eligible employers and activities are much broader in Italy and sharply limited in other countries, where vouchers are reserved for low-risk activities that do not require any specific professional training and are commissioned, with few exceptions, solely by households or private individuals who are not engaged in a business activity;

- in Italy, the restrictions regard workers (the ceiling on amount payable with vouchers by an employer to an individual worker and the ceiling on such remuneration that can be received by a worker from all employers), whereas the restrictions in other countries, both in terms of volume and amount, are focused on employers in order to prevent excessive recourse to vouchers by employers;

- the tax and contribution relief available in Italy on income from casual employment paid with vouchers is relatively greater that that available elsewhere and, above, is less selective with regard to the beneficiaries.

Text of document (in Italian)