The Chairman of the Parliamentary Budget Office (PBO), Giuseppe Pisauro, submitted a memorandum (in Italian) on the bill ratifying Decree Law 23/2020 (the Liquidity Decree), currently under examination by Parliament, to the Finance and Economic Activities Committees. After a brief description of the main measures contained in the decree and the related financial effects, the memorandum focuses on measures to support the liquidity of companies based on the issue of public guarantees through the Guarantee Fund for small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) to secure loans granted by banks and financial intermediaries. More specifically, preliminary quantitative evidence is provided on the maximum volume of guarantees that can be activated by firms, the self-employed and professionals who hold VAT registration numbers. With this maximum level of guarantees, the potential level of appropriations for the SME Guarantee Fund to secure the risks assumed is quantified, applying specific risk rates.

The direct and indirect economic effects of the pandemic have manifested themselves differently across economic sectors, affecting households and businesses throughout the country. In this context, the Government first intervened with Decree Law 18/2020 (the Cure Italy Decree), introducing welcome measures to support the finances of households and firms in the short term, sustaining employment, disposable income and financing conditions. This was followed by Decree Law 23/2020 containing measures to meet the liquidity needs of businesses. Based on the 2020 Economic and Finance Document, the measures contained in Decree Law 18/2020 and Decree Law 23/2020 should inject €750 billion of liquidity and greater access to credit into the real economy.

As part of the measures to expand companies’ access to credit, SACE will provide up to a maximum of €200 billion in guarantees to banks and other entities authorised to grant credit in Italy for loans in any form to businesses. The measures also establish a public guarantee securing SACE exposures on business loans and those of Cassa Depositi e Prestiti (CDP) assumed by 31 December 2020 on portfolios of loans granted by banks and other entities authorised to grant credit to firms that have seen their turnover decline as a result of the health emergency. Finally, public export support has been enhanced by changing the framework of previous rules, providing for a co-insurance system for non-market risks as defined pursuant to current EU legislation, under which the commitments deriving from SACE’s insurance business are assumed by the State and SACE itself in the proportions of 90 and 10 per cent respectively (€200 billion).

As part of the measures to support business continuity, the intervention of the SME Guarantee Fund has been strengthened and expanded, reinforcing the provisions of Article 49 of Decree Law 18/2020, which has been repealed. The decree basically envisages two ways to access liquidity guaranteed by the Central Guarantee Fund, which can be combined at the individual firm level: 1) a loan of up to €25,000 (in any case not exceeding 25 per cent of 2019 turnover), 100 per cent guaranteed by the Fund if a firm has incurred economic harm from the COVID-19 emergency (Article 13, paragraph 1, letter m)); 2) a loan with a 90 per cent direct guarantee and 100 per cent reinsurance in an amount equal to the greater of 25 per cent of 2019 turnover, double the wage bill for the same year and costs for working capital and investment in the subsequent 18 months for SMEs or for 12 months in the case of companies with fewer than 499 employees (Article 13, paragraph 1, letter c)). For the latter category, if 2019 turnover does not exceed €3.2 million and a firm has been adversely impacted by COVID-19, it may obtain a loan of up to 25 per cent of turnover (therefore up to a maximum of €800,000) 90 per cent secured by the Guarantee Fund, which can rise to 100 per cent with guarantees from loan guarantee consortia or other entities authorised to issue guarantees (Article 13, paragraph 1, letter n)). The quantitative analysis has focused on these measures.

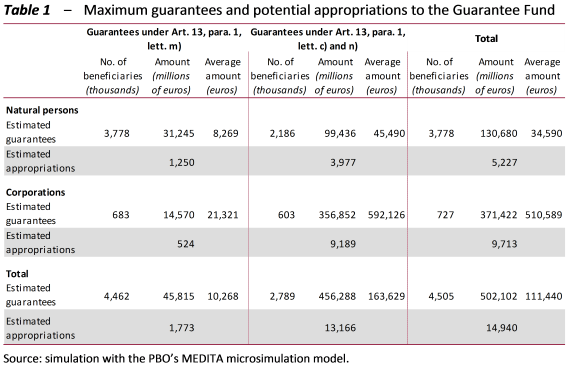

Quantitative analysis. – The analysis provides an initial quantification of the maximum volume of guarantees that could potentially be activated by natural persons and corporations and, with this maximum level of guarantees, generates an estimate, applying specific risk rates, of the potential funds that would need to be appropriated for the SME Guarantee Fund to secure the risks assumed.

This exercise can be helpful in assessing both the capacity of these measures to provide companies adequate financing to meet their possible liquidity needs and in quantifying the public resources that, given the risk of default, may be needed to meet the maximum level of required funding. Moreover, the decree does not set a ceiling on the guarantees that can be activated, unlike the new SACE Fund for large companies and, residually, for SMEs. In this case, the eligibility conditions are specified and the maximum amount of guarantees that can be activated is set at €200 billion.

Companies eligible for Fund support include firms with fewer than 500 employees, mainly SMEs (companies with fewer than 250 employees with a turnover of up to €50 million or total balance sheet assets of up to €43 million) and certain large companies (those with between 250 and 499 employees) that are normally not eligible for the Fund: overall, this pool of beneficiaries comprises about 4.7 million businesses.

A number of assumptions were adopted in performing the quantification:

1) consistent with the aim of estimating the maximum volume of guarantees that could be activated by businesses, it is assumed that those who were already eligible for the SME Fund (in accordance with the rules in force before Decree Law 18/2020 and Decree Law 23/2020) have never drawn on its support. Consequently, under the provisions of Article 13 of Decree Law 23/2020, both for these companies and for those that until the introduction of the decree were not eligible to access the Fund, a maximum guarantee of €5 million is assumed, with this amount being conditional on compliance with the other restrictions imposed by the decree;

2) no behavioural assumptions are made about companies and the decision to have recourse to the Fund: a company, if eligible, applies for a guaranteed loan in the maximum amount allowed by the decree (taking account of the constraints imposed on turnover, labour costs or the cost of capital);

3) as for the eligibility to a Fund guarantee, only loans of up to a maximum of €25,000 are automatically guaranteed and therefore open to the entire pool of firms involved. For other types of financing, credit institutions are expected to continue to assess creditworthiness, which thereby excludes the most risky companies (where possible, as in the case of corporations, these were excluded from the analysis);

4) with regard to the situation of a single company accessing the various guarantees envisaged in letters c) and n) of Article 13 on one side and letter m) of Article 13 on the other side, it is assumed that the two measures can be combined with each other: it is assumed that the guarantee of €25,000 is requested first and any additional application is conditioned by the ceiling imposed on the value of turnover, personnel costs and the cost of capital, net of the amount for which a guarantee has already been obtained.

The analysis found that for all natural persons and corporations, a maximum of up to €502 billion guarantees could be activated through the SME Guarantee Fund (Table 1). Of these, almost €46 billion (for over 4.4 million beneficiaries) would regard loans of up to €25,000. On the basis of this maximum amount of guarantees that could be requested and applying appropriate risk coefficients, the estimated overall potential commitment for the public finances amounts to almost €15 billion in the next few years.

The estimate of the volume of guarantees that could be requested and, therefore, of the consequent public financial commitment to secure the risk of default, are maximum amounts based on the unlikely assumption that all companies and self-employed workers apply for guaranteed loans in the maximum amount allowed and that banks grant these loans to all applicants, with the exception of those with a poor credit rating. In reality, the situation will differ. First, not all potential beneficiaries will be interested in obtaining a guaranteed loan in the maximum amount allowed, as, among other things, these loans will then have to be repaid within six years. Second, banks will grant loans, even if substantially or totally guaranteed by the State, only after an appropriate assessment process has demonstrated that the borrowers are sufficiently creditworthy. These considerations reduce the maximum amount of guarantees that could be requested and thus the consequent financial commitment to be borne by the State budget in the coming years.

On the other hand, however, it should be borne in mind that the provisions of the decree do not rule out the use of these guarantees in restructuring transactions involving existing loans or to guarantee loans that are currently totally or partially unsecured. In view of this possibility, banks will have an incentive to solicit these types of transactions to reduce their risk, just as there may be companies interested in improving their debt situation. These transactions would lead to an increase in guarantees that would not be fully reflected in new credit for businesses. Possible general evidence of debt that could be restructured or for which guarantees could be extended or introduced for the first time can be drawn from the exposure of corporations eligible for the SME Fund to banks and other financial intermediaries as indicated in their 2018 financial statements, which is equal to about €340 billion (of which €200 billion at medium term).

Account should also be taken of the fact that for any maximum amount of guarantees that could be activated, the quantification of the appropriation for the Fund may be underestimated. First, a risk rate was applied that reflects the performance and financial position of companies and self-employed workers prior to the crisis without taking account of the probably increase in the risk of default that is likely to also involve companies that before the COVID-19 emergency displayed no signs of financial strain. Second, the provision of almost total public guarantees could prompt banks to lend to borrowers that they would have otherwise excluded because they were too risky.

General considerations. – The measures adopted by the Government so far play a decisive role in countering the effects of the pandemic on the liquidity of firms, self-employed workers and professionals with VAT registration numbers and in preventing shortages of liquidity from triggering bankruptcies in the short term. Banks and other financial intermediaries have been put in a position to maintain an adequate flow of credit to the economy thanks to the provision of substantial public guarantees and the easing of some capital requirements decided by the ECB and the Bank of Italy. Without this, economic activity would slow down even more sharply, with effects continuing beyond the end of the pandemic.

However, the effectiveness of these measures crucially depends on the speed with which they are implemented and on the disbursement of loans not being slowed by implementation uncertainties and complex administrative requirements. Many companies, especially smaller businesses, may find themselves in a position of not being able to wait out relatively long loan disbursement procedures. Above all, the smallest loans, i.e. those equal to 25 per cent of 2019 turnover up to a maximum of €25,000, should be disbursed as soon as possible on the basis of self-certifications and compliance with anti-money laundering legislation. More careful but still rapid loan assessments should instead be reserved for larger secured loans. A delicate balance must be struck between the urgency of businesses to have their loans granted and the need for banks to evaluate their customers’ creditworthiness effectively.

With the exception of companies in default at 31 December 2019, the liquidity support measures are essentially universal. At least initially, this feature is necessary and understandable in order to enable all firms affected by the suspension of their activity, and therefore facing a liquidity crisis, to access credit. Subsequently, however, it is likely that priority will have to be given to selective measures in support of companies in the sectors most affected by the emergency. Universality makes it possible for less creditworthy businesses to apply for loans, some of which would not have survived even before the pandemic spread. In extreme cases, public guarantees could be used opportunistically for purposes other than those envisaged in the decree in support of businesses. This could well have an adverse impact on the public accounts in the medium term.

The measures are designed in such a way that the public guarantees do not necessarily have to apply to new credit, and this gives banks an incentive to ask shakier companies to renegotiate existing loans or extend of guarantees before granting any additional credit. However, these possibilities must be assessed against the fact that public resources are limited.

Finally, it is not clear whether and how loans guaranteed on the basis of the measures contained in Decree Law 23/2020 can be integrated with those obtainable using the new European COVID-19 Guarantee Fund of the EIB Group, which will provide guarantees for up to €200 billion in loans for the European economy, taking account of the fact that the public guarantees introduced with the decree could be more attractive to both companies and banks, with the risk that Italy may not take full advantage of the new instruments made available by the EIB Group.

These potential critical issues are accompanied by a number of considerations on the ability of companies to react, in the medium term, to the shock caused by the pandemic and to bear the weight of the debt that they could take on in the coming months.

The loss of turnover suffered in the last few months and those still to come will not necessarily be immediately recoverable. Firms will take some time to return to or exceed pre-pandemic profitability. Those who are able to survive the crisis will find themselves burdened by the debt they have taken on in the meantime, and it will be more difficult to access additional forms of credit. This will inevitably also be reflected in banks’ balance sheets, given the greater riskiness of their customers.

To address these aspects, a number of options for intervention are currently under discussion that, in the short term, could reduce the liquidity requirements of firms and even marginally decrease the need to resort to credit and, in the medium term, encourage the capitalisation of companies, rebalancing the equity and debt structure of their balance sheets.

In addition to measures to accelerate general government payments of suppliers already under discussion, the former category of measures includes the possibility of accelerating and simplifying tax refund procedures. The possibility of introducing selective measures, proportionate to the loss of turnover and mandatory expenditure, involving direct transfers to businesses from the State to reduce their need to borrow, is also under discussion. However, such measures would have a significant impact on the public finances.

In the medium term, the second category of tools envisages the introduction of incentives for the capitalisation of companies to rebalance their balance sheets and increase their capacity to absorb losses. However, companies could be limited by the availability of new equity capital. Precisely for this reason, discussions are under way concerning the possibility of supporting the capitalisation of companies, at least initially, with public capital.