The 2017 Budgetary Planning Report is devoted to analysing the 2017 Economic and Financial Document (EFD) and examines the substance of the parliamentary hearing of 19 April, developing and updating where appropriate, expanding on the analysis of the macroeconomic and public finance forecasts, the assessment of compliance with national and European fiscal rules and the sectoral analysis presented on that occasion.

The report is organised into four chapters. The first is devoted to an analysis of the EFD’s macroeconomic forecasts for the period 2017-2020. The second analyses the trend and policy scenarios of the public finances, with particular attention being paid to the recent corrective budget measures for 2017, highlighting their possible impact on the revenue and expenditure account of general government. The third chapter discusses the public finance policy objectives in the light of current national and supranational fiscal rules. The fourth chapter offers a preliminary assessment of the inclusion, on an experimental basis, of a number of well-being indicators (fair and sustainable well-being) and a description of the state of progress on the National Reform Programme (NRP) for 2016 and the proposals in the NRP for 2017, accompanied by a number of thematic analyses.

The macroeconomic environment

The 2017-2020 policy macroeconomic scenario in the EFD is based on a structural correction of the public accounts for 2017 – now implemented with Decree Law 50/2017 – and the proposed budget for 2018-2020, which is discussed in very general terms in the EFD. According to those proposals, the measures would provide a stimulus compared with trend developments whose main impetus would derive from a reduction in indirect taxes and the fiscal burden on labour. These measures would be offset by corrective action to increase the efficiency of expenditure, measures to prevent tax evasion, increases in a number of revenue streams and action to reorganise tax expenditures. The net impact of the budget measures (including the correction for the current year) would be small reduction compared with trend in the deficit for 2017 (two-tenths of a point) and 2018 (one-tenth of a point) and a larger reduction in 2019 and 2020 (about four-tenths of a point in the first year and half a point in the second).

In the light of the available information and a very general reconstruction of the budget measures, the PBO endorsed the 2017-2020 policy scenario while underscoring the risks associated with the international environment (the emergence of US protectionist positions, the intensification of geopolitical tensions, the end of the decline in the euro, which has favoured Italian exports), with domestic conditions (an increase in Italian interest rates as a result of the widening of spreads on government securities) and with the high degree of uncertainty currently affecting the definition of the fiscal policy set out in the EFD.

The real GDP growth set out in EFD lies within the range of forecasts produced by the PBO panel (Cer, Prometeia and Ref.ricerche, in addition to the PBO itself), albeit at the upper bound of the interval, especially in 2018 and 2019, the year in which the contribution of domestic demand to GDP growth is largest.

Taken together, the results of the endorsement exercise point to an EFD estimate of the effects of the budget measures that falls within the impact assessments conducted in the panel forecasts (despite differences in the values of the fiscal multipliers used in the forecasting models adopted by the panel members). In view of the assumed composition of the budget measures, their overall impact, for both the PBO panel and the EFD, are virtually neutral over the forecasting period.

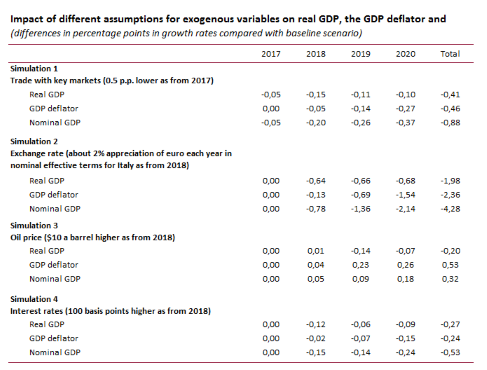

The PBO conducts an assessment of the risk factors threatening the Government’s macroeconomic scenario, performing a number of simulations that incorporate less favourable developments, compared with the EFD, in exogenous international variables and a decline in investor confidence in Italian debt. More specifically, the simulation assumed: 1) slower growth (0.5 percentage points a year in 2017-2020) in world trade; 2) oil prices that were $10 a barrel higher in each year of 2018-2020; 3) a euro that was about 2 per cent stronger a year in 2018-2020; and 4) an increase of 100 basis points in Italian interest rates in each year of the 2018-2020 period (it is assumed that the increase involves the entire curve of domestic interest rates). These changes would have an adverse impact on real growth and domestic inflation (except in the case of an increase in oil prices), with proportionately worse consequences for growth in nominal GDP.

As shown in the following table, these changes would have an adverse impact on real growth and (except in the case of an increase in oil prices) on internal inflation, with proportionately larger negative consequences for nominal GDP growth.

The public finances

The public finance scenario in the EFD clearly maintains continuity with that presented in the Draft Budgetary Plan last October, which was then implemented with the subsequent Budget Act.

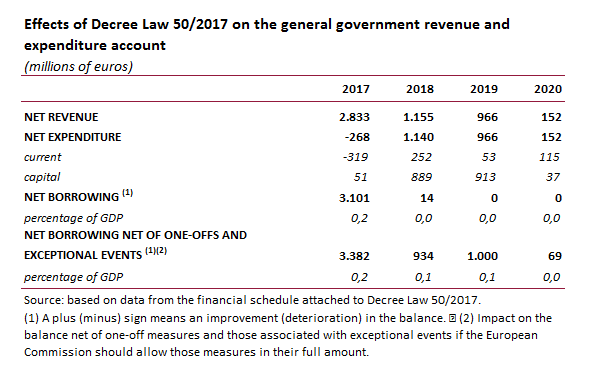

Compared with the forecast for net borrowing formulated in October, the policy forecast in the EFD diverges for 2017 only, since, following a request of the European Commission, the Government approved Decree Law 50/2017 correcting the deficit target from 2.3 to 2.1 per cent of GDP. In 2018-2019, the deficit as a proportion of GDP is unchanged on the earlier level (1.2 and 0.2 per cent respectively), with budget balance in effective terms forecast for 2020. The Government established that the improvement in the balance, equal to about 0.2 percentage points of GDP, forecast for 2018 and subsequent years thanks to the measures approved with Decree Law 50 shall be used to reduce part of the increase in indirect taxes triggered by the so-called “safeguard clauses”.

Nevertheless, maintaining the same policy targets established last October and fully deactivating the safeguard clauses for indirect taxes would make it necessary to implement measures in the coming months with an impact of about 1 percentage point in GDP in 2018 and about 1.5 percentage points in the following two years, even without considering the need to finance additional measures announced by the Government to sustain growth and employment.

The EFD presents an undefined scenario for the corrective measures to be adopted to achieve these objectives. It refers generically to both expenditure and revenue measures, including, for the latter, additional action against tax evasion. On the expenditure side, a contribution should come from the new spending review, which is incorporated in the budget cycle as from this year and is based on a top-down approach to the definition of targets. The EFD set a goal of at least €1 billion a year in savings to be achieved by central government departments. At the moment, however, the application of the new procedure appears to lack a number of important steps if the targets are to be achieved in full, such as, for example, an indication in the EFD of the structure of policy revenue and expenditure broken down by subsector, especially those of the State.

With regard to the public debt, 2016 closed with a further – albeit slight – increase in the debt/GDP ratio (to 132.6 per cent). The policy scenario, even including possible support for the banking system, envisages a slight reduction in the ratio as soon as 2017 (-0.1 percentage points) and a subsequent sharper drop to 125.7 per cent in 2020.

There are a number of uncertainties weighing on this scenario, first and foremost the start of the normalisation of monetary policy in 2018: the ECB’s reduction of its programme for purchasing sovereign debt could be accompanied by a notable increase in the cost of servicing the debt, perhaps greater than that already projected in the EFD policy scenario. Further doubts concern privatisation receipts (which have been reduced to 0.3 percentage points of GDP a year), for which insufficient information to assess credibility has far been provided so far, and nominal GDP growth that lies at the upper limit of the PBO panel’s forecasts.

The public finance objectives in the light of the fiscal rules

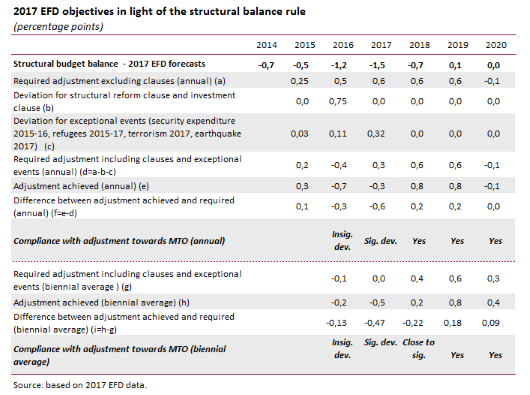

With regard to compliance with fiscal rules, the 2017 EFD confirms the objectives set out in earlier policy documents, notably the achievement of structural budget balance by 2019. The government document also leaves open the possibility of a less restrictive budget stance in 2018-2019 if EU institutions opt for a more flexible interpretation of the Stability and Growth Pact.

Some past choices, however, also affect assessment of compliance with fiscal rules in the present. The public investment plan linked to the request for flexibility in 2016 under the investment clause was only partially implemented, due in part to normal delays associated with the beginning of the new programming cycle for the Structural Funds. Although this did not affect the level of investment funded entirely by national funds, the slower-than-expected implementation of the programme in 2016 may have contributed to the fall in overall level of public investment compared with 2015 (-4.5 per cent), a violation of one of the conditions for granting the flexibility under the clause.

A definitive conclusion by the European Commission will be issued after the publication of the Spring Forecasts, considering first the precondition for eligibility for the clause – which, as noted, requires that the overall expenditure aggregate not be lower in 2016 than in 2015 – and, second, the actual amount of expenditure to be considered for the purpose of the clause.

The decision to implement a fiscal policy for 2016-2017 that brings the budget close to the limit of a significant deviation from the fiscal rules in annual terms means that there is a risk of a significant deviation on a biennial basis in 2017. The inadvisability of an excessively restrictive fiscal stance appears to have been implicitly acknowledged by the European Commission itself, which – in calling for a structural adjustment of 0.2 percentage points of GDP – has in fact only requested that the deviation be rectified in annual terms.

On the other hand, the results of the monitoring of the expenditure benchmark, which are only partly affected by the challenges of measuring potential GDP and the output gap, appear to be more encouraging than those for the structural balance. This once again underscores the problems associated with a system of rules based mainly on variables that are exposed to significant measurement difficulties. In this regard, the recent agreement, approved by the EU Council (ECOFIN) at the end of last year, to formulate mid-year recommendations for countries such as Italy that have not yet achieved the medium-term objective (MTO) both in terms of changes in the structural balance and growth in the expenditure benchmark (net of discretionary revenue measures) is a welcome development.

In 2018-2020, the policy scenario for the structural balance appears fully compliant with European and national rules. Nevertheless, the debt/GDP ratio, although expected to decline, will not do so sufficiently to ensure compliance with the numerical rule within the policy horizon.

Well-being indicators and the National Reform Programme

The inclusion for the first time of a number of well-being indicators (fair and sustainable well-being) in the EFD is another welcome development. Supplementing information on developments in the main macroeconomic variables with information on variables relevant for the quality of life and the environment provides a more complete picture of the information on which economic policy action is based. It permits an ex-post assessment of the results achieved and provides greater transparency on public decisions. However, a number of critical issues have emerged regarding the presentation of policy forecasts of indicators for the 2017-2020 period. Unlike the trend forecasts, these projections should reflect the effects of the measures contained in the budget package and the reforms outlined in the National Reform Programme (NRP). In April, with no information on the composition of the budget measures, it would be preferable for the EFD to report only a trend assessment of the indicators accompanied by the objectives that the Government intends to pursue (possibly consistent with the commitments taken at the European level with the Europe 2020 Strategy and internationally with Agenda 2030 for Sustainable Development), postponing the presentation of the policy developments in the indicators until after the approval of the Budget Act, for example in the Report to the competent parliamentary committees scheduled for 15 February each year.

With regard to the content of the NRP, the programme limits itself to confirming the reform plans outlined in earlier policy documents. This probably also reflects the fact that it was prepared at the end of the legislature. The chapter provides a brief description of the state of implementation of the provisions of the 2016 NRP for a number of specific areas (labour market, social policies, the tax system and tax evasion, public administration and education), of the European Commission’s observations from last February and of the reform proposals contained in the 2017 NRP.

Among the labour market policies announced, particular importance is given to the commitment to reduce the tax wedge on lower incomes, and specifically on second wage earners in households, suggesting a form of taxation that fosters female employment. The chapter contains two in-depth analyses. The first shows that the differences between international tax systems do not seem sufficient on their own to explain the poor performance of female employment in Italy. Furthermore, the Italian tax system is not the most unfavourable in terms of the presence of factors that penalise female participation in the labour market, thanks in part to the fact that the basic tax unit is the individual and not the household. On the contrary, there is a robust positive correlation between the female employment rate and the supply of public services. The second in-depth study conducts a review of temporary and permanent incentive measures introduced in recent years to stimulate job creation and increase productivity. It emphasises in particular that new relief measures should only be implemented after an examination of the effectiveness of previous or existing measures in order to target the choice among different possible instruments more effectively and after a survey and reorganisation of those still in place to avoid fragmentation of the tax relief system and overlap and competition between measures (e.g. among those adopted at the regional or sub-regional level).

With regard to social policy, the “Inclusion Income” will be introduced in a system still characterised by multiple means-tested measures with different eligibility criteria focused on specific categories of beneficiaries that do not reduce the risk of poverty among the most vulnerable segments of the population. The extension of the new instrument to all households in a situation of absolute poverty will depend on the appropriation of additional resources and the possibility of the broader integration of the various existing measures into one instrument. Estimates performed in 2013 by the Minimum Income Working Group established by the Ministry of Labour and Social Policies put the cost of a measure that will completely bridge the existing gap between disposable income and the poverty level for all households in a situation of absolute poverty at between €5 and 7 billion.

Finally, with regard to taxation and, in particular, the Government’s announcement that it would continue to reduce the fiscal burden to support growth and competitiveness, an in-depth analysis looks at developments in the tax burden in recent years. It finds that the decline mainly involved taxation of capital, through changes in the structure of corporate taxation and more contingent measures to facilitate and encourage investment. In particular, considering the sum of direct taxes and IRAP (the regional business tax), we find that between 2013 and 2015 (the last year for which information on individual taxes by general government body is available) revenue declined by half a percentage point of GDP, a drop that increased to nearly 1 point in 2016. However, this decrease appears to have been highly skewed towards corporate taxes. IRES (corporate income tax) and IRAP revenue in the last eight years has fallen by about 1.7 percentage points of GDP (from 5.4 per cent in 2007 to 3.6 per cent in 2015).