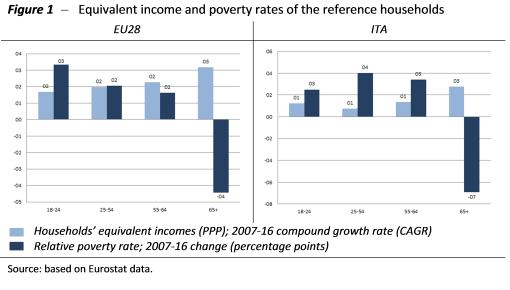

Inspired by the International Monetary Fund (IMF) paper Inequalities and Poverty Across Generations in the European Union, this Flash aims at exploring more in depth the case of Italy. According to the IMF, in EU28 countries the highest negative impact of the crisis was borne by the youngsters (aged 18-24) while the elders (65+) have seen their economic condition improved. Is Italy adequately described by this picture?

The IMF analysis fails in taking into account a structural aspect of the Italian socio-economic system, pre-existing the crisis and highlighted by the crisis: that is the important role of Italian traditional households, in which children usually prolong their co-living with parents far beyond the completion of their studies. In the years of the crisis, this permanence within the household of origin has played a protective role, providing informal assistance against unemployment and poverty risk. The aforementioned effect may have embraced not only youngsters aged 18-24 but also young adults belonging to the second age bracket used by the IMF (25-54 years).

Looking at Figure 1, while for the aggregate of the EU28 countries it is confirmed that the youngsters aged 18-24 are the most hit by the crisis (they show the lowest growth rates in disposable incomes together with the sharpest increase in relative poverty rates), for Italy the evidence reports something different. Here the strongest impact was borne by those aged 25-54 and to a lesser extent by those aged 55-64 years (the growth in disposable incomes is slightly higher than for young people but combined with a more pronounced deterioration in the relative poverty rate).

If in the past this traditional feature of Italian households has been surely useful to alleviate the impact of the crisis, nevertheless it must be clearly underlined that the same characteristic constitutes also an historical weakness for Italy. Looking forward, it would be advisable not to continue to rely indefinitely on informal assistance provided by parents, but to strengthen formal active labour policies accessible to everyone on the basis of the same set of rules and aimed at promoting career progresses or, in case of unemployment, at reinserting young individuals at work as soon as possible.

Support by parents is not equally distributed across young generations (it is not available to everybody in the same way) and might not have sufficient targeting and effectiveness as formal well-designed policies. Moreover, it should not be underestimated that parents’ support implies in most cases a reduction in their equivalent disposable income, and consequently fewer resources that the elderly can use for their needs, including health care and long term care. Also this latter effect can arise in very differentiated manners according to the economic conditions of the household of origin, revealing another possible unsatisfactory aspect of an overreliance on informal support to youngsters and young adults within households.

Net of informal support offered by the households of origin, economic and living conditions of young Italians during the crisis would appear more aligned with what happened in the EU28 average. Therefore, policy guidelines outlined in the conclusion of the IMF paper remain valid, with particular reference both to the preparation of effective unemployment support and active employment policies for times of economic crisis, as well as to the implementation of other measures to stimulate a more rapid exit from the parents’ household. In fact, regardless of economic cycles, skills and talents of youngsters and young adults are potentials that deserve to be freed and exploited for the advantage of all young individuals themselves and of the society as a whole.