The President of the Parliamentary Budget Office (PBO), Giuseppe Pisauro, spoke today in the hearing (in Italian) before the bureaux of the Chamber and Senate Budget Committees, meeting in joint session to examine the 2020 National Reform Programme (NRP) for 2020 and the Report to Parliament prepared pursuant to Law 243/2012. In the document presented, the PBO Chairman reviewed recent trends in the global and national macroeconomic environment and the impact of the new government measure now being prepared on the main public finance variables. Pisauro also offered a number of general comments on the announced sectoral measures and analysed, in the light of the Conclusions of the July European Council, the areas of intervention of the future Recovery Plan, also in relation to the lines of action set out in the 2020 NRP.

Macroeconomic conditions. – About seven months after the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic, the global economy seems to be heading towards recovery. However, in some countries the coronavirus is still very widespread, and in those where the peak was reached some time ago the risks of a second wave remain high.

Cyclical conditions in the Italian economy, which were already weak in 2019, worsened with the spread of the epidemic at a pace and intensity unprecedented in times of peace. After falling steeply in April, the more timely quantitative indicators began to recover in May, albeit very gradually. With the easing of the restrictive measures, economic activity rebounded in several sectors, although the levels of activity clearly remain lower than those recorded a year ago. A more detailed discussion of the current economic situation and the update of the medium-term projections for the Italian economy will be reported in the PBO’s Report on Recent Economic Developments, which will be published next week to take account of new data on employment, inflation, retail sales and wages, in addition to second quarter GDP growth, which will be released by Istat on 31 July.

The Report to Parliament and developments in the public finances. – On 23 July, with an additional Report – drafted pursuant to Law 243/2012 – the Government asked Parliament for authorisation to update the plan for returning the structural balance to the path of adjustment towards the medium-term objective (MTO) with an additional budget deviation of €25 billion in 2020, €6.1 billion in 2021, €1.0 billion in 2022, €6.2 billion in 2023, €5.0 billion in 2024, €3.3 billion in 2025 and €1.7 billion from 2026. Given the nature of the planned measures, the effects in terms of the general government borrowing requirement and the net balance to be financed (NBF) for the State budget differ: in the former case, the impact amounts to €32 billion in 2020 and is equal to that for net borrowing in subsequent years; in the case of the NBF, on both an accruals and cash basis, the impact amounts to €32 billion in 2020, €7 billion in 2021, €2.5 billion in 2022, €5.3 billion in 2023, €4.8 billion in 2024, €3.3 billion in 2025 and €1.7 billion from 2026.

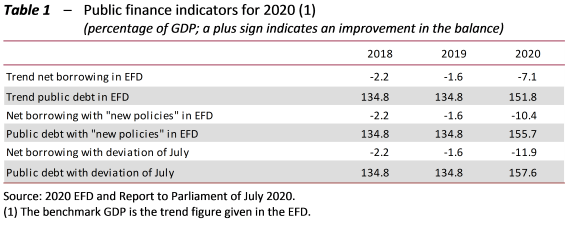

Considering the new request for €25 billion (1.5 per cent of GDP) in 2020, general government net borrowing would reach 11.9 per cent of GDP and the public debt would rise to 157.6 per cent of GDP, taking account of the deviation of €32 billion, i.e. 1.9 per cent of GDP (Table 1) in terms of the borrowing requirement.

These figures consider the estimate of trend GDP contained in last April’s Economic and Financial Document (EFD).

Recall that for 2020 the estimates for the trend public finance variables contained in the EFD (including the financial effects of Decree Law 18 and Decree Law 23 of 2020, equal to 1.2 per cent of GDP) show general government net borrowing of 7.1 per cent of GDP and public debt of 151.8 per cent, while under the “new policies” scenario (i.e. also considering the effects of Decree Law 34/2020, equal to 3.3 per cent of trend GDP), the deficit is equal to 10.4 per cent of GDP and the debt/GDP ratio comes to 155.7 per cent.

The deterioration compared with last year’s deficit is substantially attributable to a similar extent to the direct quantitative effects of the decrees already approved (4.5 points of GDP) and that in preparation (1.5 points of GDP) and the combination of the underlying trends in the public accounts, with an impact on the deterioration in economic conditions ‑ especially in terms of lower revenue ‑ connected to the measures to contain the spread of COVID-19 (the lockdown).

The Government, although not providing details in this regard, confirms the objective specified in the previous report in April of bringing the debt/GDP ratio to the euro-area average over the next decade with a reduction strategy that, in addition to achieving an adequate primary budget surplus, will be based on economic growth deriving primarily from the revival of public and private investment.

The available information shows a sharp deterioration in the public finance balances compared with last year, which will worsen further as a result of the expected new measures. Considering the estimates for the macroeconomic scenario indicated by the PBO in its latest Report (which took account of the effects of Decree Laws 18, 23 and 34), the deficit would be slightly more than half a percentage point of GDP greater than that forecast by the Government. The debt/GDP ratio, impacted by its various determinants, notably the more unfavourable contribution of the contraction in output, could be about three percentage points higher. With the deviation for which authorisation is sought, debt could exceed 160 per cent of GDP.

Given the significant uncertainty that characterizes the forecasts for both macroeconomic variables and the public finances, more updated information will be available following the release of new data in the first week of August. For the public finances, the uncertainties of the macroeconomic scenario are compounded by those concerning the data from the regular monthly monitoring of the main expenditure and revenue aggregates.

New measures: wage supplementation. – The request to Parliament to authorise an increase in net borrowing is motivated, among other things, by the need to continue to support employment through the extension of benefits from the Wage Supplementation Scheme for COVID-19-related reasons.

Determining the advisability of the request for additional resources to finance wage supplementation first requires an assessment of the scope of application of the measures taken so far. However, quantifying this aspect is currently a difficult challenge, not only due to the limited availability of information but also because that information covers all employers who have made use of the wage supplementation programme for COVID-19 reasons, including those who could have used the mechanism even without the expanded rules introduced with the anti-crisis decrees.

The data drawn from the periodic reports and from the first INPS monitoring data for the number of hours of wage supplementation actually used in March, April and May – which covers all employers who requested support for COVID-19 reasons, including those who could have accessed the programme for the normal reasons (those not made ineligible by the cumulative limit on the use of the mechanism, the so-called “counter”) – reveal a number of interesting developments: 1) the number of monthly wage supplementation hours authorised increased drastically in April and May before falling by half in June; 2) in the March-May period, wage supplementation used amounted to just over 1.1 billion hours, with a peak in April of more than 590 million hours, followed by a sharp slowdown in the subsequent months; 3) if we restrict the scope of observation to April-May (a period common to the data on hours authorised per reference month and the hours actually used), the percentage of hours drawn comes to about 63 per cent (the number of wage supplementation hours used came to just over 943 million, compared with authorised hours of about 1.5 billion), which may be found to be overstated a posteriori, since the denominator may lack hours pertaining to April and May but authorised in March; and 4) the number of workers who at 9 July had received at least one COVID-19 wage supplementation payment (including those who could have received support even without the measures introduced with the anti-crisis decrees) amounted to around 5.5 million, a significantly smaller number than that identifiable on the basis of the assumptions in Technical Reports accompanying the decrees (over 8 million) and which, moreover, fell significantly between April and May (from 5.2 to 3.5 million).

This information, although partial, suggests that the use of COVID-19 wage supplementation could be somewhat lower than expected in terms of beneficiaries, duration and percentage drawn, thus generating cost savings compared with officially estimates.

However, greater expenditure for the labour market could be necessary if additional weeks of COVID-19 wage supplementation were to be authorised in anticipation of new challenges in the second half of the year (for example, a resurgence of the virus or a slower recovery in economic activity), or if it were deemed necessary to extend wage supplementation to ensure that the extension of the ban on firing until the end of the year is sustainable for businesses.

In general, the advisability of extending wage supplementation free of any cost to the company applying for support should be assessed (normally, a firm is required to make a “co-payment” on drawings, based on the overall remuneration that would have been due to the worker for the suspended working hours and the duration of the suspension), reserving this relief selectively for the businesses most affected by the crisis and actually experiencing financial distress. A cross-analysis of INPS monitoring data and the electronic invoicing data of the Revenue Agency in the first half of 2020 compared with the first half of 2019 shows that while about one-third of the hours of ordinary wage supplementation, exceptional wage supplementation and support from the bilateral funds was used by companies with turnover losses of over 40 per cent, more than a quarter of the hours were drawn by companies that did not experience any reduction. Finally, the Report to Parliament does not make it clear whether the request for an increase in net borrowing will also be used to finance the extension of one-off allowances for para-subordinate workers, the self-employed and professionals, which, under current legislation and taking account of the grant for VAT number holders, are only being disbursed through May at the latest. As with a possible extension of wage supplementation, an extension of the one-off allowances would increase expenditure intended to protect workers.

New measures for businesses. – The Report mainly refers to two areas of intervention, albeit without providing quantitative information or specifying which measures will be used. These areas are measures to safeguard the liquidity of companies and those to support the most affected industries.

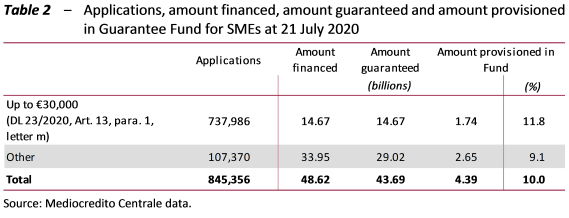

Only general comments can be offered on the need for new financial resources above and beyond the effort already made to support firms using the available data, which are summarised in Table 2.

Between 17 March and 21 July, more than 845,000 applications (approximately 20 per cent of the total potential pool of beneficiaries) were received by the Guarantee Fund, corresponding to some €48.6 billion in loans, with corresponding guarantees of €43.7 billion (89.9 per cent of the loan value on average) (Table 2). An average provision of about 10 per cent was made in respect of the loan guarantees, for total provisions of €4.4 billion. The percentage provision is clearly higher for loans up to €30,000, at almost 12 per cent, compared with 9 per cent for other loans. As of 21 July 2020, the remaining resources available on the Guarantee Fund amounted to €2.2 billion. Assuming no changes in conditions (the relative weight of loans up to €30,000 compared with others, the guarantee percentage and the characteristics of the applicant firms), the Fund could guarantee an additional €25 billion in loans.

According to the daily “counter” available on the Guarantee Fund website maintained by the Ministry for Economic Development (MISE), on 24 July the number of applications reached about 900,000, with additional requests for financing of €11 billion compared with that authorised at 21 July (+22.5 per cent), for the most part accounted for by loans larger than €30,000. If the entire additional amount were authorised, using the average percentages registered so far, it can be estimated that guarantees could have increased by €9.4 billion, with additional provisions of €0.88 billion (about 40 per cent of the resources still available at 21 July).

However, taking account of the fact that the mechanism for granting guarantees has only begun to work expeditiously in the last two months and that the most recent applications for financing appear to be for larger amounts on average than earlier applications, the value of loans covered by public guarantees could still grow. It can therefore be presumed that the Guarantee Fund will require refinancing in the coming months to meet additional applications from companies, which can be submitted until 31 December 2020.

Another consideration is that even with no change in the number of guarantees granted, the provisioning requirement of the Guarantee Fund could increase as a result of a deterioration in the credit standing of firms that received guarantees.

As regards tax obligations, for 2020 businesses are already benefiting from the generalised abolition of the balance payment for 2019 and the first payment on account for 2020 for IRAP (the regional business tax) and, limited to the firms most directly affected by the health emergency, an exemption from payment, for 2020, of the first instalment of municipal property tax, and the TOSAP and COSAP public land occupation fees. In addition, temporary suspensions of payment of other taxes have also been implemented, although most of these will have to be paid by the end of the year.

In the Technical Report accompanying Decree Law 34/2020, the estimated amount of the suspended payments, based in part on an ex post assessment of payments in March and April 2020, is equal to €20.6 billion (compared with the approximately €27 billion originally estimated). Similarly, considering that the initial estimates for suspended payments for May and June, equal to around €10 billion, could also be revised downwards, the actual value of the suspensions could also be lower. A possible postponement of payments to next year would require new resources to offset the loss of revenue in 2020.

New measures: local authorities. – The Report to Parliament refers to the need to support local authorities to cope with the reduction in their revenue in recent months as a consequence of the health crisis, with the aim of ensuring the delivery of public services at the local level as well.

The estimated reduction in revenue still to be offset (net of cost savings and taking account of revenue support measures already implemented) is still being assessed.

Some preliminary information on local authorities is contained in the methodological notes attached to the decrees for allocating the Funds established with Article 106 of Decree Law 34/2020, containing an appropriation for local authorities of €3.5 billion for 2020, of which €3 billion for municipalities and €0.5 billion for provinces.

For regions, the agreement on the amounts to be allocated with a forthcoming measure provides for an appropriation of €1.5 billion for regions and autonomous provinces.

On the basis of the financial framework defined by these documents, the additional resources planned to support local authority budgets should amount to about €4.4 billion, broken down as follows: €1.1 billion for municipalities, €350-500 million for provinces, €1.2 billion for ordinary statute regions and €1.6 billion for special statute regions. These amounts do not consider the local public transport sector, which could receive additional resources.

Next Generation EU and the Italian NRP. – The agreement reached by the European Council of 17-21 July 2020 confirmed the establishment of the Next Generation EU instrument (NGEU), one of the two pillars – together with the resources of the 2021-2027 Multiannual Financial Framework (MFF) – supporting the Recovery Plan for Europe, presented at the end of May by the European Commission as a response to the economic and social effects of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Compared with the proposed NGEU formulated in May by the Commission, the overall scale of the instrument is unchanged (a total of €750 billion, at 2018 prices), but the allocation of resources among the various measures has changed. The resources, raised on the market by issuing debt with maturities of between 3 and 30 years, will be channelled to the Member States in the form of grants in the total amount of €390 billion and loans of €360 billion. The funds must be committed by 2023, while the associated payments must be made by 2028.

The NGEU is a package of various initiatives: by far the largest is the Recovery and Resilience Facility (RRF), with a resources of €672.5 billion, of which €312.5 billion in the form of grants and €360 billion in loans. Loans cannot exceed 6.8 per cent of the beneficiary country’s forecast gross national income (GNI) for 2020; for Italy this would be equivalent to loans of more than €120 billion.

For grants, 70 per cent of the €312.5 billion available under the RRF will be allocated in 2021-2022 and the remainder in 2023, using two slightly different allocation criteria that should benefit countries in which the economic impact of the pandemic was greatest. Italy could obtain grants under the NGEU in the maximum amount of about €87 billion (at 2018 prices) between 2021 and 2027, considering the appropriations indicated in the Conclusions of the European Council for the various programmes.

In order to determine the net benefit/cost of the activation of NGEU, the repayment obligations of each Member State in the following years must be assessed. A relatively precise assessment of this expenditure is difficult to quantify. Using a “mechanical” estimate of the contributions that each country may have to pay in the coming years, for Italy the net benefit – defined as the difference between the total transfers admissible under the NGEU and the contribution to the repayment of the EU debt used to finance the instrument – would amount to over €46 billion (at 2018 prices), or about 2.6 per cent of 2019 GDP (at 2018 prices). In nominal terms, this net benefit would be the largest among the EU countries.

Note that for all countries the advantage of the NGEU lies in the timing of incoming and outgoing transfers. In fact, incoming funds will arrive in the period between 2021 and 2027, in line with the need to provide an immediate response to the economic and social consequences of the pandemic. Conversely, most resource outflows will presumably occur as from 2028.

The disbursement of NGEU funds is subject to the Member States drafting National Recovery and Resilience Plans that set out a coherent programme of public reforms and investments for the following years, specifying intermediate and final targets for the reforms and investments. Investment projects must be completed within seven years and reforms within four years of the adoption of the decision to grant support to the Member State.

The Government announced in the 2020 NRP that it intends to publish its recovery plan next September, together with the Update to the Economic and Financial Document (the Update), and to forward it to the European Commission by the mid-October deadline with the Draft Budgetary Plan (DBP). In the NRP, the Government announced the outline of the Plan, which will be based on increasing investment, expanding spending on research, education, innovation and digitalisation and on reforms designed to increase potential growth, competitiveness, equity and social and environmental sustainability. As regards the reforms, measures have been announced in the field of civil and criminal justice, education, and labour and tax policies.

Overall, it can first be observed that the NRP lists a vast programme of sectoral measures, not unlike those contained in the previous NRP and does not appear to take the opportunity to identify strategic priorities. These could be used to prepare the Recovery and Resilience Plan in the autumn so as to focus the resources of the European instrument on key areas of intervention.

Second, the NRP does not provide information on how the use of extraordinary resources will be incorporated within in the ordinary budgetary framework, i.e. the multiyear decision on the allocation of resources. In fact, the Recovery Plan is also aimed at strengthening measures that will presumably continue to require resources even when operational and activities that will also require ongoing funding.

The Recovery Plan to be presented to the EU institutions must contain, under penalty of a negative assessment from the European Commission, detailed programmes of interventions, indicating the individual measures, the cost, the methods for effective implementation, including the proposed intermediate and final targets and the related indicators, and the estimated impact on the economy. The preparation of the actual Plan to be submitted to the European institutions will therefore require the thorough development of policies for the individual measures and detailed technical work.

In conclusion, the preparation of a credible, detailed, coherent plan for public reforms and investment, with a certain timeframe for its implementation, represent a special challenge for Italy, also considering the urgency with which it must be prepared. This will require a significant and rapid upgrading of government’s working methods, in particular the capacity to plan (and implement) public policies.