The Chairman of the Parliamentary Budget Office (PBO), Giuseppe Pisauro, spoke today at an informal hearing (in Italian) before the Budget Committee of the Chamber of Deputies as part of the parliamentary examination of the bill ratifying Decree Law 34/2020 (the “Revival Decree”). Pisauro reviewed the provisions of the legislation, focusing attention on their financial impact and their effects on the sectors and categories to which they are addressed. For a number of the measures contained in the decree, he also set out the results of quantitative analyses conducted using the PBO microsimulation model to identify the pool of beneficiaries involved, the benefits deriving from the measures and their distribution based on certain salient characteristics of the beneficiaries.

The decree has a significant impact on the public finance balances. The measures it contains produce a deterioration in general government net borrowing of 3.3 per cent of GDP (€55.3 billion) in 2020 and 1.5 per cent (€26.1 billion) in 2021, in line with the estimates provided in the Report to Parliament and in the Economic and Financial Document (EFD) presented in April. Its financial impact would raise the general government deficit to 10.4 per cent of GDP in 2020 and 5.7 per cent in 2021.

Most of the measures in the decree have a similar impact on the three key public finance balances with the exception (in 2020) of a number of specific large-value measures whose impact on the balances differs. In particular, the €12 billion appropriated for the provision for the payment of certain, liquid and enforceable liabilities of local authorities have a larger impact on the borrowing requirement than on net borrowing. A number of large-value measures only impact the net balance to be financed of the State budget, including €44 billion for the so-called “Targeted Fund” (“Fondo destinato”) of Cassa Depositi e Prestiti (CDP) and €30 billion to supplement the fund for the granting of guarantees in favour of SACE and CDP established as part of the economic support measures contained in the Liquidity Decree.

The measures increase spending by €49.8 billion this year, €5.6 billion in 2021 and €6.4 billion in 2022, while reducing revenue by €5.6 billion in 2020, €20.5 billion in 2021 and €28.3 billion in 2022. The increase in outlays for this year mainly concerns current expenditure, largely reflecting the resources allocated to support workers and firms. The impact on capital expenditure in 2020 essentially derives from measures to support small and medium-sized enterprises and the amounts allocated to the Civil Protection Department for national emergencies and to the extraordinary commissioner for the COVID-19 emergency. The reduction in revenue for 2020 to a large extent reflects the elimination of the balance payment for 2019 and the first payment on account for 2020 of IRAP (regional business tax). In the following two years, the impact on revenue essentially reflects the reduction in indirect tax revenue due to the elimination of the safeguard clauses providing for increases in indirect taxes.

We can formulate initial comments on one specific large-value measure in the decree and offer some general remarks.

First, the impact on the public finances of certain provisions aimed at supporting and reviving the economy requires a more thorough examination. The measures would be implemented through the recapitalisation of corporations through CDP, which for this purpose has been authorised to establish a pool of earmarked assets(the Targeted Fund), separate from the assets of the CDP. It will be funded by assets and legal provisions of the Ministry for the Economy and Finance (MEF), against which CDP would issue participating financial instruments to the MEF itself. On the basis of the capital contributed, which comprises specifically issued government securities (up to €44 billion), CDP would undertake financing operations to provide enterprises with the resources for capitalisation initiatives. The Targeted Fund can also issue government-guaranteed bonds. Pending their use in recapitalisation operations, the liquid assets of the fund will be held on a special Treasury account.

The summary tables accompanying the decree show the measure having an impact only on the net balance to be financed of the State budget. Net borrowing would not change since the operation involves the acquisition of financial items, which are excluded from this balance by definition. According to the Technical Report, as the contribution of assets and legal provisions does not involve cash transfers it would not have any effect on the borrowing requirement. The reports accompanying the measure make no mention of any effects on general government debt.

Although the operation is relatively complex and the time profile of the impact on the accounts is subject to factors that are currently unknown, it should be underscored that capitalisation operations carried out through the Targeted Fund per se represent an increase in general government debt. However, any more accurate assessment of the time profile of the impact on debt depends on a number of factors that have not yet been determined. These factors could even represent, through the payment of the liquidity into the Treasury account, an instrument for financing the borrowing requirement until the liquidity is drawn to fund the original purposes of the programme.

The decree provides for certain large-value interventions, which when added to those already envisaged under Decree Law 18/2020 (the “Cure Italy Decree”) will increase general government net borrowing by 4.5 per cent of GDP in 2020. It strengthens and extends the duration of some of the provisions of Decree Law 18/2020 and provides for new measures affecting a broad range of sectors.

A vast selection of instruments will be rolled out, and an equally extensive range of specific administrative procedures and practices will be implemented. The legislation will require numerous implementing decrees and, in some cases, a prior declaration of the compatibility of the provisions with EU legislation from the European Commission. In general, the effectiveness of the measures will also depend on the speed of their implementation.

The many emergency provisions are accompanied by a number of measures of varying structural scope. These include measures to strengthen the National Health Service, expand hiring in schools, universities and research institutes – although some of this was already planned ‑ and increase investment in research. The decree also provides incentives to boost spending in the private sector, such as expenditure on building renovations or the purchase of low-emission vehicles.

A more important measure from the point of view of the persistence of its effects over time appears to be the elimination of the safeguard clauses providing for increases in VAT and excise duties. Bear in mind that the impact of the elimination of the safeguard clauses on the deficit does not create fiscal space for new policies but does increase the transparency of public finance balances’ dynamics caused by policies adopted in the past.

Given the current health and economic emergency, the decree necessarily provides for measures that distribute financial resources to numerous sectors, with an especially large impact on current expenditure, and short-term tax exemptions. However, in the coming months both the emergency measures and the more structural interventions will have to be reassessed in the context of a more comprehensive strategy for budgetary policy. It will be necessary to make strategic choices about the sectors to which greater or fewer resources will be channelled, about the future of the tax system and about the revival of capital expenditure in an environment in which it will again be necessary to achieve a primary surplus in order to enable a lasting reduction of debt as a ratio of GDP.

More specifically, the tax measures – represented by a fragmented set of postponements of payments within the current year, reductions for 2020 only, postponements to 2021 and definitive abolitions of tax increases ‑ will have to be placed within a comprehensive reorganisation of the system in the years to come. This is especially necessary, partly in consideration of the specificity of certain taxes such as IRAP (which was reduced sharply for this year), the revenue of which contributes significantly to financing the National Health Service.

The results of the quantitative and qualitative analyses reported in the hearing are summarised below.

Income support measures for workers and families. – Decree Law 34/2020 reinforces the strategy initially undertaken to counter the impact of the pandemic on the labour force with Decree Law 18/2020. It focuses first and foremost on the extension of exceptional wage supplementation measures and one-off allowances for self-employed workers and a number of more marginal categories of payroll employment. Workers who are unable to benefit from one of these two instruments (for example, the working poor, represented by occasional workers with an income of less than €5,000 a year, agricultural workers with fewer of 50 days of work, etc. ) and meet the associated eligibility requirements could find protection under the Citizenship Income or the Emergency Income programmes.

The PBO microsimulation model was used to conduct a preliminary analysis of the combined effect of the income support measures taken as a whole (including those envisaged under legislation enacted before Decree Law 18/2020 and Decree Law 34/2020), highlighting the distribution of benefits across Italian households broken down by selected socio-economic characteristics. The exercise considered all forms of transfer payable for April (wage supplementation and various allowances for employees, allowances for self-employed workers and the Emergency Income).

In the absence of detailed information, currently unavailable, account was taken of plausible asymmetries in recourse to the various programmes by conducting a scenario analysis in which various take-up rates were assumed on the basis of a classification of sectors by degree of risk in relation to the type of restrictions on the activity still existing. We assume: a high risk (a high take-up rate for the measures) for sectors in which activity is still suspended under the restrictions (those connected with tourism, restaurants and recreational and cultural services and smaller segments of retail trade, transport and other service activities); an average risk for the manufacturing sector, which although not subject to restrictions has been indirectly impacted by the crisis, with the exclusion of the food and chemical-pharmaceutical industries; and a low risk for the remaining sectors. Overall, around 11 per cent and 46 per cent of the sectors were judged to be at high or medium risk, respectively (in terms of their value of production). A rate of recourse to wage supplementation of 90 per cent was assumed for companies in high-risk sectors, 50 per cent in medium-risk sectors and 20 per cent in low-risk sectors. The average take-up rate for the various forms of wage supplementation mechanism is just over 40 per cent.

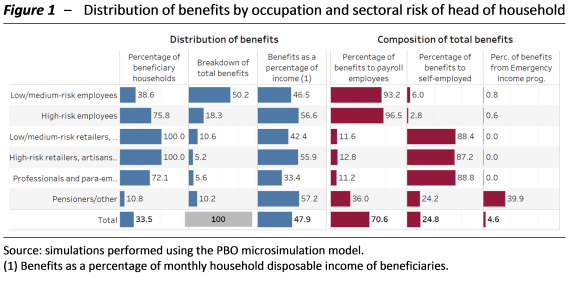

Overall, benefits were paid to about a third of Italian households, with the proportion differing depending on the nature and selectivity of the benefits received and on the employment status of the members of the households (employees, the self-employed or other), and amounted on average to 47.9 per cent of pre-crisis monthly household disposable income (Figure 1).

Households with heads belonging to the categories covered by universal allowances, such as the €600 allowance for beneficiaries enrolled in the special funds of the general mandatory pension programme (retail traders, artisans and farmers), are all eligible for the transfer. The situation changes for households with self-employed household heads (professionals and para-employees). These workers also receive a lump-sum allowance, but it is subject to certain conditions regarding their level of income and the decline in their revenues. As a result, about 72 per cent of the households concerned are eligible for the benefits.

Households with heads who are payroll employees have a lower benefit coverage rate overall. Employees are mainly covered by wage supplementation programmes, which are intrinsically selective in that benefits are only paid in the event of suspension or reduction of working activity. This means that the proportion of beneficiary households is highest among those with a head of household who is a payroll employee in the sectors most severely affected by the emergency (75.8 per cent in the case of high-risk sectors, compared with 38.6 per cent in low/medium-risk sectors). However, since low/medium-risk sectors account for a large share of the economy (54 per cent of output), direct transfers to households with an employee head of household in these sectors make up about half of total disbursements (compared with 18.3 per cent for those in high-risk sectors).

The very low proportion of beneficiaries among households with a non-working head of household (about 11 per cent) is the result of the explicit exclusion of pensioners, who are assumed to have suffered no decline in income. For this category, the benefits may derive either from the presence of workers (not heads of household) in the household or from the Emergency Income programme. For this category of households, the Emergency Income mechanism accounts for about 40 per cent of total benefits received.

Overall, around 70.6 per cent of the benefits are paid to employees, 24.8 per cent are paid to the self-employed, while about 4.6 per cent of the total resources are appropriated for the Emergency Income programme.

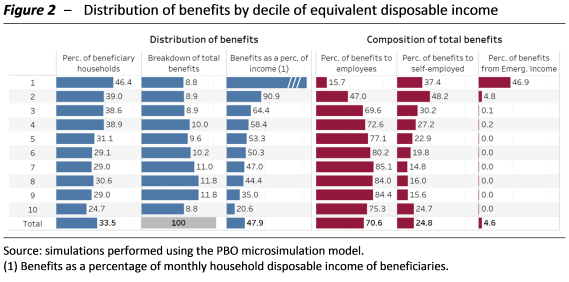

The distribution of beneficiaries by income decile shows that a larger proportion of beneficiary households are in the lower deciles, with the percentages ranging from 46.4 per cent of households in the first decile to 24.7 per cent in the tenth decile (Figure 2). On the other hand, the distribution of total resources across deciles is substantially uniform. Since benefits paid under wage supplementation mechanisms are only partially correlated with income due to the presence of ceilings and the other one-off allowances are paid in lump-sum amounts, benefits represent a larger share of the income of the poorest. The transfers amount to 90.9 per cent of the average pre-crisis monthly household income of beneficiaries in the second decile, compared with 20.6 per cent for beneficiaries in the tenth decile. For the first decile, the Emergency Income accounts for just under 50 per cent of total transfers received.

Finally, around 54 per cent of benefits go to households residing in the North, while 26 per cent go to households in the South. Benefits paid to employees make up about three quarters of the benefits that flow to the North, compared with a national average of 71 per cent. In the South, the share of total benefits deriving from the Emergency Income mechanism is double the average (8.4 per cent, compared with 4.6 per cent).

In the coming months, it will be necessary to closely monitor benefit payments, both to check developments in spending for the various programmes and to obtain information on employment trends in the various sectors. It is essential for the National Social Security Institute (INPS) to disseminate data on applications for and payments of benefits in a timely and scheduled manner and, above all, to publish the data on the effective use of hours authorised under wage supplementation mechanisms.

With the changes implemented by the Decree Law 34/2020, the amount, duration and eligibility requirements of one-off allowances have been diversified. In the absence of clear information on differences in the impact of the crisis, this differentiation raises a number of questions, especially given the possibility, which cannot be excluded a priori, that the allowances could be extended beyond May, as is already happening with wage supplementation programmes.

With regard to the receipt of benefits under multiple programmes, it is still not wholly clear even after the clarifications contained in the decree – except where expressly provided for – whether one-off allowances and wage supplementation benefits (in particular the CIG COVID-19 mechanism), unemployment benefits, the Citizenship Income and the Emergency Income can be combined. It would be advisable to consider inserting a “framework” provision that establishes the mutual incompatibility between all benefits provided under COVID-19 emergency programmes or that clarifies its scope in the manner adopted in Article 98 of the decree with regard to the allowance paid to beneficiaries active in the sports sector.

Finally, the increase in the amount available to self-employed workers and professionals without a separate pension fund in May compared with the amount granted in April is explained by the fact that in the meantime the measure has become more selective, with the inclusion of a requirement that beneficiaries have suffered a serious loss of turnover/income.

Measures for firms. – The measures contained in the decree include, among others, provisions to support the liquidity and financing of companies and those suspending or eliminating tax payments.

The first category of measures are intended to cover the period following the peak of the emergency, which the measures introduced so far were designed to address. These are generally measures with more stringent eligibility requirements, differentiated by size and legal form of the company involved. A general objective of these measures is to bolster the capitalisation of companies, in order to avoid the risk that the credit support instruments implemented in the emergency phase will leave firms too heavily burdened with debt, forcing them to allocate cash flows in coming years to debt repayments rather than financing investments. This is all the more important at a time when changes in demand and business models are likely to require firms to undertake expensive conversion initiatives.

The measures adopted for medium-sized and larger companies are aimed at strengthening their financial structure by ensuring a better balance between their sources of funding, thus creating more favourable conditions for the investments that will play an essential role in the recovery and the upgrading of production. The incentives for equity capital injections therefore seem to complete the preferential treatment of corporate financing, which had hitherto been primarily focused on debt capital. Note also that the extension of the possibility of resorting to bond issues for a subset of companies benefiting from the tax credit, through the privileged channel of the SME Capital Fund introduced with the decree, is strictly subordinated to the contribution of additional equity capital to the company, thus ensuring greater balance between external and internal sources of financing.

For the beneficiary companies, this preferential treatment is temporarily accompanied by the ACE, considerably increasing the incentive to strengthen capitalisation. Nevertheless, it should be emphasised that only a small number of companies are eligible for the benefit, since companies in the eligible revenue class represent less than 5 per cent of corporations (almost 50,000, excluding sectors not covered by the measure) and about 25 per cent of total revenues.

For larger companies set up as joint-stock companies, the same objective is pursued by the Targeted Fund. However, most companies, i.e. those with a turnover of less than €5 million, are not eligible for the incentives to strengthen their capitalisation. The latter may not only experience a greater deterioration in their balance sheets, but the difficulties in obtaining additional financing could slow their investment and hinder their growth.

Finally, it should be noted that the incentives for strengthening capital are subject to a total spending limit, which may be insufficient to benefit all the companies eligible for support, and their financial effects will only manifest themselves from 2021: in particular, the size of the incentive for companies depends on their overall loss, which can only be determined after the closure of their 2020 accounts.

The most notable of the second category of measures include those providing for actual exemptions from the payment of taxes, as in the case of the abolition of the balance payment for 2019 and the first payment on account for 2020 of IRAP for most firms. Since this represents a significant generalised tax reduction that also applies to many sectors that have been less affected by the emergency, the measure is less consistent with the aim of channelling public resources to the businesses most affected by the crisis that appears to characterise this new round of interventions. Even in the initial years following its introduction, IRAP was a bone of contention, and the business world has repeatedly called for its elimination. If this measure were to be a first step in this direction, it would be necessary to rethink the overall framework of business taxation and the financing of the healthcare system.

Ecobonus and transferable tax credits. – The measure, which entirely funds the incentives for eligible projects from the public budget, appears aimed not only at supporting the construction sector, but also at extending the pool of beneficiaries, eliminating the obstacle to using this incentive for property owners who did not have sufficient liquidity or sufficient taxable income to benefit from the credit.

At the same time, however, it is important to bear in mind that the measure could be exploited for tax avoidance or speculative purposes. The amount of the credit significantly reduces the conflict of interest between suppliers and buyers in respect of the cost of the subsidised projects, as both parties benefit from increasing expenditure up to the maximum facilitated amount. For example, in the case of companies that provide both energy upgrading and ordinary renovation works to the same customer, the parties could find it attractive to overestimate the cost of the former, in order to finance the latter under the concessionary regime. The effective use of public resources for the purposes intended by the measure will therefore depend on the effectiveness of any anti-avoidance mechanisms envisaged.

With regard to financial effects, there is a risk of underestimating the costs for the purpose of net borrowing. If the tax credits transferred and used as set-offs were classified as “payable” (insofar as they can be used regardless of the presence of taxable income in the tax return of the buyer), the associated amount would entirely impact net borrowing in 2021-2022, rather than being distributed over time on the basis of the instalment schedule envisaged for using the credits. This consideration refers both to renovations for which the amount of the benefit has been increased and the time for its use has been reduced, and for the remaining renovation projects in 2020-2021 for which the measure simply allows beneficiaries to opt for the transformation of the credits into transferable form.

Local government finance: resources for the emergency and advances for the payment of trade payables. – The main measures to support local authorities include the appropriation of extraordinary resources and the grant of cash advances to pay trade payables. In addition, the scope of local government intervention in supporting businesses in their territory has been expanded, in compliance with the Temporary framework for State aid envisaged by the European Commission.

The amounts appropriated appear significant although the data available on the cash flows of local authorities in the first quarter of 2020 do not currently enable any reliable assessment of the adequacy of the resources envisaged under the measure to meet the overall needs that will emerge over the next few months as a result of the health emergency. Their timely allocation will enable public administration to cope with the budget imbalances that begin to appear, while monitoring effective developments will make it possible to assess real requirements.

The grant of cash advances to pay trade payables replicates past measures, demonstrating that the problem of late payments, although gradually improving, has not yet been definitively resolved. However, in the short term this measure represents a useful tool for various purposes: to supply liquidity to businesses that work with public administration; to forestall the opening of the infringement procedure announced by the European Court of Justice for excessive payment delays; and to limit the application of the penalty mechanism, which starting from 2021 requires local authorities that do not comply with payment times to recognise additional provisions. However, this temporary remedy must not lead to the postponement of processes to improve the efficiency of managing the public accounts that are needed to avoid the use of irregular accounting procedures and commercial practices. In the absence of the adoption of these efficiency enhancing processes, as well as criteria for allocating resources that ensure funding for the fundamental functions of all local government, the temporary remedy represented by cash advances could produce the opposite effect in the medium term, since the need to repay advances will drain liquidity from governments that have had to use those advances, thereby contributing to the risk of creating new payment arrears.

From an accounting standpoint, it seems imprudent to assume that the share of advances that will be used by local governments to pay their trade debts on capital account will have no impact on net borrowing, given that the capital expenditure of territorial governments is recognised on an accruals basis at the time of the cash outlay.

Healthcare sector measures. – Decree Law 34/2020 increases the resources earmarked for strengthening the healthcare system by a total of €4.85 billion in 2020, €0.609 billion in 2021 and €1.609 billion in 2022. They include: 1) an increase of €1.5 billion for 2020 in the National Emergency Fund; 2) another €1,467 billion, again for 2020, for the implementation of the reorganisation plans to strengthen intensive care facilities, which will be transferred to the extraordinary commissioner; 3) an increase in direct funding of the National Health Service (NHS) equal to €1.8 billion in 2020, €0.6 billion in 2021 and €1.6 billion in 2022; and 4) limited additional funding to further strengthen the military healthcare system.

In addition to refinancing programmes, Decree Law 34/2020 envisages a series of specific measures and indicates the interventions authorised. The part of the cost of these measures that is not funded through the special accounts of the extraordinary commissioner is charged to the financing for standard national health funding requirements. The total cost, where the regions implement the authorised programmes, is therefore greater than the refinancing granted in the coming years, and in 2021 in particular: it amounts to about €1.7 billion, of which €1.2 billion for territorial assistance, almost €400 million for hospitals and about €100 million for training. The new measures will likely be financed with funding already approved (which envisages an increase of €1.5 billion in 2021 over 2020). Additional resources could be appropriated in the future. The level of funding of the NHS for 2022 has not yet been established.

The alarm linked to the spread of COVID-19 has shone a light on the need to strengthen the NHS in general – not only to respond to current emergency – which will have to be addressed. It is likely that this will require an even greater increase in resources than already decided. At this stage, however, it seems more necessary than ever to assess the cost effectiveness of the use of resources and the priorities that have emerged both during the pandemic and in the preceding period.

For example, improving of the territorial assistance network appears to be an essential objective, given the numerous shortcomings that have already been reported for some time now and the evident insufficiency of the capacity to manage emergencies at the local level. This has probably contributed to increasing the burden on hospitals and worsened the overcrowding experienced in the most acute phase of the pandemic. The increase in the number of beds in intensive and semi-intensive care wards also appears necessary if we are to handle unexpected emergencies and manage the peaks of influenza epidemics. However, it would be desirable incorporate broad flexibility into the organisation of services, both in the use of the staff – who in ordinary circumstances could also be used to support other services, such as emergency services – and in the management of facilities, in view of the fact that the most modern hospitals, beds can be rapidly transformed into intensive care units. Furthermore, it has never been more important for resources to be managed in an informed manner consistent with appropriateness objectives, in order to respond to the substantial demand that could also originate primarily with private-sector service providers/producers.