The Board member of the Parliamentary Budget Office (PBO), Alberto Zanardi, spoke today at a hearing (in Italian) before the Social Affairs Committee of the Chamber of Deputies, which is examining Bill C. 2561 containing “Enabling authority for the Government to support and promote the family” (the Family Act).

The substantial document filed with the Committee reviews the objectives, tools and resources for the implementation of the enabling authority set out in the Family Act (section 1); examines the measures announced in the National Recovery and Resilience Plan (NRRP) ‑ presented to Parliament last January and now under review – as they pertain to the objectives of the Family Act, which cannot be overlooked in any assessment of the latter’s potential (section 2); analyses the current spending behaviour of families with children on education and on non-formal and informal learning and existing financial support measures (section 3); provides contextual information on female participation in the labour market, the difficulties of reconciling work and private life and the gender gap (section 4); offers an international comparison of social protection expenditure for families with children and a brief description of the main measures implemented in France and Germany (section 5); and concludes with a number of general comments on the Family Act (section 6).

Social protection expenditure for families/children in Italy is lower than that in all other EU27 countries with the exception of Malta and the Netherlands (1.1 per cent of GDP in 2018, compared with 2.2 per cent for the EU27 average, 2.4 per cent for France and 3.3 per cent for Germany). Furthermore, a large proportion of Italian expenditure goes into cash benefits (83 per cent, compared with an EU27 average of 62.1 per cent and close to 60 per cent in France and Germany). Expenditures on family and child allowances and the resources allocated to benefits in kind such as nurseries and preschools or similar are both relatively low. Despite significant progress over the years, the gender gap is still large by international standards and pervasive in many areas, as underscored by the results of the EU gender equality index. Italy’s scores in the various domains are always worse than the EU average, with the exception of the health domain. The domain with the most disappointing results is work (63.3 points, compared with an EU28 average of 72.2), followed by power (48.8 points, compared with an EU28 average of 53.5), time (59.3 points, compared with an EU28 average of 65.7) and knowledge (61.9 points, compared with an EU28 average of 63.6).

The Family Act has essentially two objectives: 1) reversing the decline in the birth rate through support for families with children and the recognition of the social value of educational and learning activities, including non-formal and informal learning, for children and young people; and 2) increasing female employment, including measures to facilitate work-life balance. They are interconnected, since the burden of caring for children, but also the elderly and the non-self-sufficient, still falls mainly on women.

To achieve these objectives, multiple tools are identified: a universal monetary transfer to support families with dependent children without limitations on use, such as the universal allowance; tax breaks and monetary transfers for deserving expenditure; incentive measures, such as strengthening incentives for female employment or the introduction of flexible forms of work to promote the reconciliation of family and work life; the direct provision of public services, as in the case of expanding the availability of socio-educational services for children; regulatory measures, for example relating to the procedures for using parental leave.

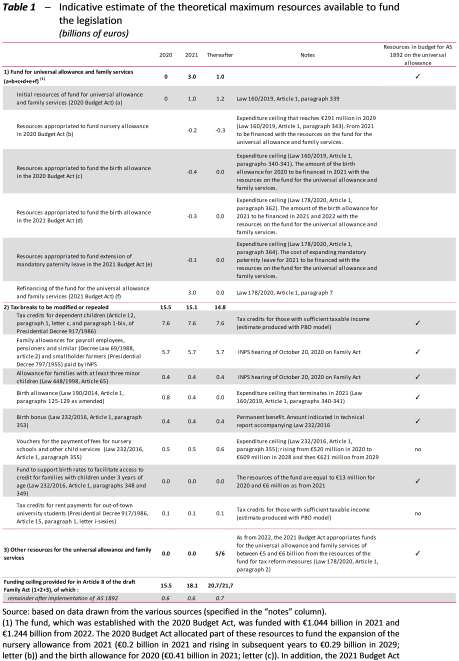

On the one hand, the Family Act has been superseded in a number of salient aspects by recent measures introduced with the 2021 Budget Act (the experimental extension of mandatory paternity leave to 10 days; contribution relief for hiring unemployed women; the allocation of resources to the Municipal Solidarity Fund to finance the expansion of municipal social services and increase the availability of places in nursery schools; the establishment of a fund to support female entrepreneurship) and, above all, the imminent final passage of the enabling bill on the unified and universal allowance (AS. 1892), which will also have a decisive impact on its budget. The two bills share the entire budget, except for the portion concerning the modification/repeal of just two existing measures: vouchers for the payment of fees for nursery schools and other child services and the IRPEF tax credits for rent payments for out-of-town university students. The resources from the repeal of these two measures amount to about €0.7 billion (Table 1), which would therefore represent – if implementation of the universal allowance used all the resources currently provided for in AS. 1892 – the resources available to finance the measures provided for in the Family Act once the universal allowance is finally approved.

On the other hand, the potential of the Family Act is enhanced by a number of lines of action explicitly indicated in last January’s NRRP. The current version of the latter accompanies the Family Act measures that have budgetary effects on current account with capital expenditure in order to bridge gaps in the supply of public services at the territorial level, seeking to eradicate educational poverty, enhance the prospects of young people, increase youth employment and promote the reconciliation of work and private life, as well as announcing more far-reaching reforms. The Family Act and the NRRP must therefore be considered in an integrated manner, given that they share objectives and part of the measures and the possible impact on the financial resources that could be made available through the NRRP for the implementation of the Family Act as well.

The (clear) objectives and the (many) tools present in the bill are framed by rather general principles and directive criteria governing the enabling authority, which leave many of the fundamental design choices for the measures announced to the legislative decrees implementing the enabling authority. These choices concern four aspects in particular.

- First, the selectivity of the various measures, i.e. determining whether public economic support, albeit universal, should be granted to all in equal measure or differentially, taking account, depending on the objectives, of the financial circumstances of the family or individual. The choice will depend on the resources available to implement the enabling authority, but also, and above all, on redistributive considerations, given that many categories of non-mandatory deserving expenditure tend to be made more frequently by the wealthiest families. Furthermore, attention should be paid to the incentives for the specific educational and cultural consumption that the Family Act wishes to encourage. More specifically, in order to act as effective incentives, the new measures should focus mainly on families located in the lower part of the income distribution, for whom some of the deserving expenditures to be encouraged are relatively limited as a proportion of total family expenditure (for example attendance at cultural events or educational trips).

Based on information drawn from the Istat survey of household expenditure in 2017, supplemented with the administrative data from ISEE (equivalent economic status indicator) returns and tax returns, an analysis was conducted of family spending on the educational activities of children and young people in both public and private schools (tuition and fees, meals and transport services, school books, school courses and trips) and on activities connected with non-formal and informal learning (non-school books, sports activities, summer camps and playrooms, music and dance courses and lessons) (sections 3.1 and 3.2 of the hearing).

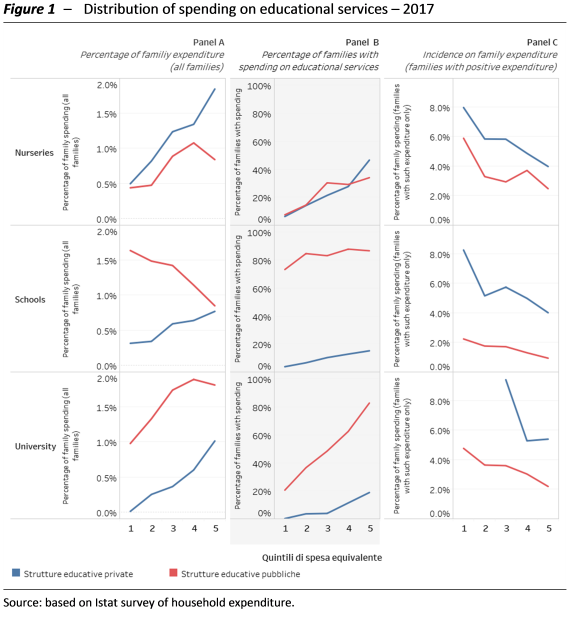

Educational spending, as well as that on non-formal and informal learning, is significantly polarised towards wealthier families in all segments except that of public schools (Fig. 1). In particular, such expenditure as a proportion of the total expenditure of user households decreases as their economic circumstances improve (panel C), but this effect is more than offset by the fact that the poorest households use the services in question less (panel B) with the result that the proportion of such expenditure for all households increases as we go from the poorest to the richest (panel A).

An example is the case of private nurseries: the proportion of spending on fees and meals is equal to about 0.5 per cent of total family spending for the first quintile and about 1.9 per cent for the fifth quintile (panel A). This mainly depends on the lower use of these services by families with lower purchasing power (6 per cent of households incur expenses for educational services in the first quintile, compared with 45 per cent in the fifth quintile – panel B), while for the (few) “poor” families who use such services, the proportion of spending on nurseries can be very high (about 8 per cent of total expenditure, compared with just under 2.6 per cent for the fifth quintile – panel C).

The exception is, not surprisingly, represented by expenditure for public schools, for which the proportion of the expenditure of all families decreases as financial capacity increases since, as a result of compulsory schooling, the share of user families is very high and substantially constant for all expenditure quintiles. Over half of the families in the first quintile spend on educational services in public schools, with a burden equal to 2 per cent of total expenditure (about double the figure for families in the fifth quintile).

- Second, it is necessary to evaluate what role to give direct public intervention and, conversely, what role to give private-sector action in choosing the combination of tools to be deployed. It is necessary to decide whether the incentives (for example, for deserving expenditure to foster educational growth) should involve the supply of public services, thus including these services in public supply standards (supply-side policies), or be driven by family demand and the provision of support tools to alleviate the burden of spending to purchase services for children (demand-side policies), or some mix of supply- and demand-side policies. However, the effectiveness of instruments to provide financial support for families’ demand for services is strictly dependent on the availability of these services and therefore coordination between supply-side and demand-side policies is necessary. If the former are not expanded, the allocation of additional resources to support family demand risks favouring only people residing in areas that already offer such services, to the detriment of those residing in municipalities that do not provide them.

An analysis of the availability of nursery schools around the country shows that in 2018 authorised places could serve about 25.5 per cent of potential users (of which about half were publicly operated) and that effective uptake (i.e. actual users per 100 resident children aged 0-2 years) at public or officially authorized private facilities was equal to 14.1 per cent. Both of these indicators varied widely around the country. Focusing on municipal nurseries, in many regions of the South the supply of public facilities, although lower than the national average, was not fully taken up by families: under-use of public services is found in Abruzzo (66.1 per cent) and in Basilicata (66.8 per cent), while greater take-up, potentially leading to shortages of public places, can be found in Tuscany (93 per cent), Lazio (90.8 per cent) and Lombardy (90.3 per cent).

The under-use of early childhood educational services is in most cases due to the specific decision of families, dictated by the child’s age or health (42.2 per cent) or the presence of a family member who can take care of the child and/or a desire to not delegate the educational function (38.5 per cent). Reasons for rationing supply (cost, remoteness of facilities, lack of demand) emerge on average in 15.8 per cent of cases, with greater frequency in the North and in the suburban municipalities of metropolitan areas. The burden of rationing could, however, be underestimated by these responses, given the rate of early enrolment in kindergartens – which are less expensive for families – especially in the South, thus suggesting that fees for nurseries could be unsustainable. Finally, demand for childcare services could grow as a result of the expansion of female participation in the labour market and the rise in the female employment rate, that could potentially stem from policies intended to promote greater flexibility in the labour market and encourage female employment and entrepreneurship contained in both the Family Act and the NRRP. It could also reflect the strengthening of measures to reduce the costs of access to nursery schools announced in the legislation under review here.

- Third, in the case of demand-side policies, i.e. financial support for families to use such services, it is necessary to select the most appropriate instrument, namely tax incentives (deductions from taxable income or tax credits subtracted directly from taxes) or monetary transfers for specific expenditures. The former are unsuitable for supporting the poorest families as many have insufficient taxable incomes and tax liabilities in the first place. In addition, the size of such incentives is based on individual income, while eligibility for measures to support expenditure on children should be based on an indicator of a family’s ability to pay (for example, the ISEE). Finally, the taxation of individual income would be further complicated by giving it a purpose – supporting the education of children and the reconciliation of life and work – for which it is unsuited. Therefore, if the most appropriate instrument would be a tied monetary transfer, it would be possible to consider gradually concentrating support for the care of children and their growth and education in a single spending instrument, the universal allowance, earmarking part of it for the latter purpose, possibly by imposing eligibility criteria. The result would be a simplification of the current system, characterized by a multitude of specific measures of sometimes limited scope. Alternatively, one could consider a spending instrument to be combined with the universal allowance, with similar characteristics to the latter, or the expansion and extension to other areas of non-formal and informal learning of the so-called “culture allowance”, which gives families a budget for expenditure in a range of specified areas while leaving the final choice about the composition of this educational spending to the individual families themselves.

- Fourth, family support policies should be carefully coordinated between different institutional levels. For example, in the case of nursery schools, any national-level expansion of measures to reduce the fees charged to families, as envisaged in the provisions of the Family Act, could in reality induce municipalities to increase those fees in order to transfer the increased public resources from families to municipal budgets. This could be avoided by transforming support for families into transfers of resources to municipalities in return for a corresponding decrease in fees or an improvement in the supply of services, or by requiring that the size of the national family allowance to support the cost of nursery schools be determined using benchmark pricing valid throughout the country.

If the Family Act is properly formulated and implemented, it could represent an opportunity: 1) to strengthen and make permanent – and therefore certain – a number of important experimental programmes designed to support parenthood and gender equality; 2) to provide universal support that can also be used by the poorest families in order to ensure equal opportunities in growth and in formal, non-formal and informal educational paths for children regardless of the economic circumstances of their family and foster real cultural change; and 3) to reorganise and systematise a fragmented system of programmes established by multiple pieces of legislation. However, this assumes additional financial resources can be found, since the imminent approval of the enabling bill on the universal allowance will eventually drain off most of the funding provided for in the Family Act. In view of these financial constraints, but also to ensure adequate coordination between the various lines of intervention, it is necessary to develop an integrated vision of the Family Act with the future NRRP. The two measures must go hand in hand, complementing each other. Recall that the version of the NRRP presented in Parliament last January provided for an expansion of the nursery and integrated services plan to promote work-life balance, also with the aim of rebalancing supply around the country, increasing school hours and therefore expanding the supply of educational services, and increasing infrastructure and the availability of territorial assistance services and networks for people with disabilities or the non-self-sufficient. With regard to gender equality, one of the three horizontal priorities of the six missions into which the plan is structured, initiatives are envisaged to encourage the participation of female students in the STEM disciplines and foster more highly qualified female employment as well as provisions to grant contribution relief for the hiring of women and support for female entrepreneurship.