Alberto Zanardi, member of the Board of the Parliamentary Budget Office (PBO), testified at a hearing before the Parliamentary Committee for Fiscal Federalism. In his remarks, Zanardi, after reviewing the state of implementation of fiscal federalism and the prospects emerging in the light of the exit from the emergency triggered by the pandemic, focused on the possible consequences of the announced reform of the current structure of local taxes, the degree of involvement of local government entities in the implementation of the National Recovery and Resilience Plan (NRRP) and the role that the latter can play in narrowing the territorial and infrastructural gaps that characterise Italy.

The exit from the pandemic crisis marks a decisive step for the institutional and financial structure of Italy’s system of intergovernmental relations. On the one hand, the extraordinary financing approach deployed in response to the crisis, which involved specific interventions to compensate subnational governments for the decrease in revenue and increase in spending they experienced as a result of the pandemic or regulatory measures taken by the government, is coming to an end. On the other, implementation of the NRRP has begun, with numerous measures designed to strengthen the infrastructure resources of local authorities to enable them to deliver services to the public, helping to bridge territorial disparities. At the same time, however, the latter poses a significant challenge for the planning and implementation skills of local governments.

Going beyond the emergency support measures and returning to the ordinary system of intergovernmental financial relations should lend renewed impetus to the implementation of fiscal federalism, which even during the past two years of crisis has registered a number of significant developments for municipalities: the grant of additional resources, the review of the equalisation system and the start of the review of the methodology for determining standard requirements for the purpose of allocating the Municipal Solidarity Fund. Recall that the completion of fiscal federalism (in particular its regional component) is included among the “enabling reforms” envisaged by the NRRP, the regulatory aspects of which are to be completed by the first half of 2026. From this perspective, the definition of the essential service levels (ESLs) for municipal and regional functions other than the health service is key. This should support the determination of the standard requirements relevant for equalisation and pertinent to the implementation of the NRRP. Consistent with a clearer linkage between standard needs and specific service levels expressed as ESLs or provided on average in municipalities, the vertical component of the Municipal Equalisation Fund, financed by transfers from the State budget, should be strengthened in order to make central government’s role in guaranteeing social and citizenship rights more visible, overcoming the current reluctance of municipalities with greater financial resources to support, through horizontal equalisation, less well-endowed governments. This could also be the result of the review of municipal taxation within the framework of the announced tax reform.

Local public finance arrangements should be affected by a number of actual or potential new developments envisaged in the enabling bill recently approved by the Council of Ministers. In particular, these concern: IMU (municipal property tax), with the reform of the real estate registry; municipal and regional additional personal income tax, whose transformation into a surtax has been announced; and IRAP (regional business tax), which is expected to be abolished. Given the involvement of the main local taxes, the implementation of the enabling authority cannot ignore the issue of fiscal federalism and the problems that currently affect the exercise of fiscal autonomy by local governments. It will be crucial if and to what extent the proposed measures to revise decentralised taxation can preserve (or re-establish) adequate scope for subnational entities to exercise their revenue-generating autonomy, a constitutive element of the reform of fiscal federalism.

The enabling bill first addresses the issue of the revision of cadastral income on two fronts: the first, immediately operational, involves a detailed correction of the classification of properties, with no change in the structure of the assessment process; the second, which is more forward looking, envisages undertaking a complex procedure for estimating indicators connected with market values in preparation for the revision of cadastral incomes, without immediately applying this for taxation purposes. This is intended to improve the ability of the cadastral system to value properties appropriately and lays the foundations for reducing the current inequity in the distribution of the levy, caused by uneven deviations between cadastral values and actual property values.

The enabling bill also provides for the transformation of regional and municipal income tax levies into surtaxes, i.e. additional levies no longer calculated in relation to the original tax base but rather as a direct percentage of the income tax liability. However, a closer reading of the enabling legislation traces a slightly different picture for regions and municipalities. For the former, the legislation provides for the application of a basic rate that, for all regions taken together, would generate the same revenue generated by the existing regional income tax base rate, permitting adjustments in rate within specified limits. For municipalities, however, the legislation establishes a surtax whose range of adjustment must be determined in a manner that will generate, for all municipalities taken together, revenue equal to that currently produced by the application of the average municipal income tax rate. Based on the incomplete information available at this point, regions would likely experience no change in standard fiscal capacity, i.e. that determined by the revenue deriving from the application of the basic rate. The potential fiscal effort of these entities could change depending on how the adjustment limits for the surtax are set. This appears to differ from the system proposed for municipalities. An examination of the language in the enabling bill indicates that, for the entire category as a whole, the surtax would generate a maximum revenue equal to that produced today by the average rate of the municipal income tax levy. If this is the case, it follows that municipalities that currently adopt higher municipal income tax rates than the average for the entire category will see revenue from application of the maximum rate of the surtax decline from that generated by the current municipal income tax. A number of simulations using 2020 income data show that revenue generated by applying the maximum rate of the future surtax (equal to the ratio between revenue from current municipal income tax and IRPEF (personal income tax) revenue) would be less than the revenue currently generated by municipal income tax for about 50 per cent of municipalities (corresponding to 66 per cent of the population).

From the point of view of the allocation of resources among local entities, given the importance of the equalisation mechanism in the distribution of those resources, the redefinition of the standard rate to be used in calculating the fiscal capacity of the new tax will be crucial. Today, although no basic rate of municipal income tax has been defined, a standard rate of 0.4 per cent for the purposes of calculating equalisation is still used. Accordingly, the application of higher rates is considered fiscal effort and is not equalised. Given the complexity of equalisation mechanisms, it will be necessary to perform simulations with different scenarios for calculating fiscal capacity to fully understand the effects of the transition to the surtax approach.

Finally, the enabling bill provides for the gradual elimination of IRAP without explicitly identifying alternative sources of revenue to make up the shortfall, while acknowledging the need to ensure adequate resources to finance the health system. In 2019, IRAP generated revenue of about €24 billion, of which just under 42 per cent comes from government entities and about €600 million from the use of the tax instruments employed by the regions. The actual revenue at the standard rate on the tax base of the private sector to be compensated would therefore come to about €13.7 billion. A debate offering a number of solutions to this issue has emerged, including the possibility of replacing IRAP with an additional levy to the corporate income tax (IRES) whose revenue would go to the regions. If this were adopted, careful consideration must be given to the redistributive effects of the differences between the two taxes in terms of taxpayers involved (a broader pool of taxpayers in the case of IRAP, while that for IRES would be restricted to corporations), the tax base (profits and interest expense for the former tax, profits alone for corporate income tax) and the territorial distribution of that tax base. These redistributive effects would be offset by the equalisation system only for the portion of revenue considered to be standard.

As already noted, the NRRP may have a significant impact on the ability of local authorities to offer services to their citizens – helping to strengthen the infrastructure resources they need to perform their functions – and narrow disparities between local authorities and territories along a path of gradual convergence. A conspicuous share of the investment that will be spurred by the NRRP involves local governments as implementing bodies, obviously in those parts of the Plan that concern areas within the responsibilities of non-central government entities (especially health and social services).

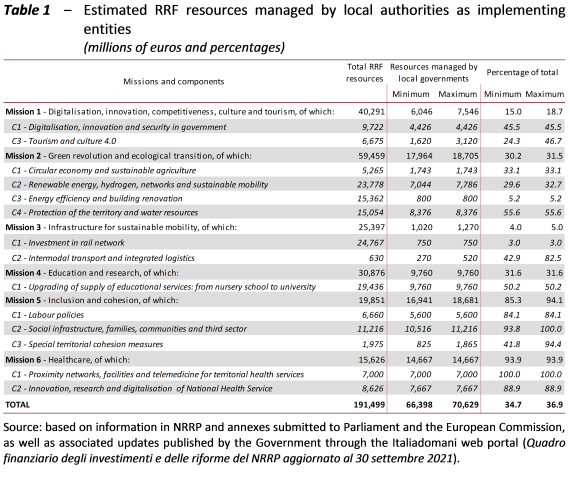

A relevant variable for measuring the effort of local governments in implementing the Plan is the volume of financial resources that they must handle as implementing entities, together with the timing of the execution of the projects, which can be estimated roughly by examining the time profile of the expenditure. Based on the annexes to the version of the NRRP approved by the EU Institutions and with regard solely to the resources made available through the Recovery and Resilience Facility (RRF) (i.e. the preponderant part of the resources for Next Generation EU), it can be estimated that local governments will manage between €66 billion and €71 billion as implementing entities (approximately 34.7-36.9 per cent of the total RRF resources allocated for Italy) for all the missions in the Plan (Table 1). Over the same period, local authorities will also be asked to implement the measures financed by the Complementary Fund to the NRRP (€30.6 billion) and other NGEU instruments (beginning with €13.5 billion of grants to be disbursed by REACT-EU by 2022).

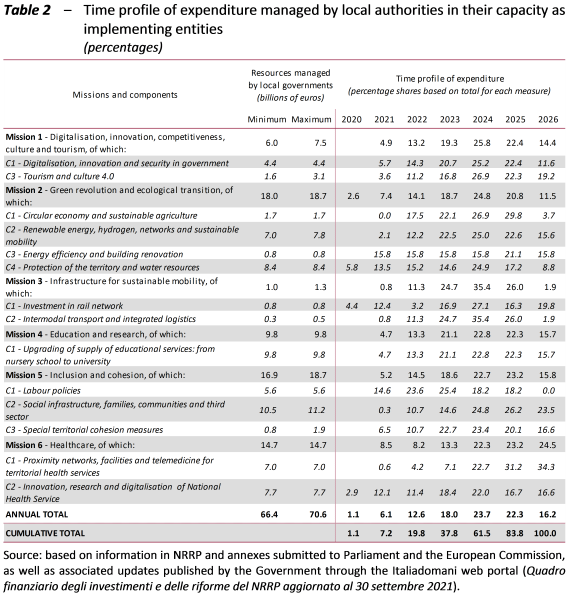

As for timing, the annexes to the NRRP indicate that the programmes are mainly expected to be finalised in the second half of the time horizon covered by the Plan. While expenditure incurred as from 1 February 2020 could be financed through the Recovery and Resilience Facility and close to half of the loans should fund interventions already envisaged under current legislation (regardless of the activation of the Plan), by 2022 less than 20 per cent of expenditure would be disbursed, while 46 per cent of disbursements would be concentrated in the 2024-2025 period (Table 2). Considering the maximum value of the estimated interval indicated above (€70.6 billion), the expected timing implies that local authorities would handle expenditure related to the implementation of the NRRP amounting to about €16 billion each year in 2024-2025. Assuming that 75 per cent of this spending is additional, it would amount to €12 billion per year. The latter value is equal to more than 40 per cent of the average annual value of capital expenditure carried out by local governments in 2018-2020, a period characterised – moreover – by an increase in such expenditure after the steady decline that began in 2009: in 2020, the capital expenditure of local authorities grew by more than 10 per cent for the second consecutive year, reaching €31.2 billion (+26.1 per cent compared with €24.7 billion in 2017). Assuming a further increase on the order of over €10 billion annually over three years certainly raises questions about the ability of the entities involved in the implementation of the projects to cope with the administrative burden associated with these expenditure flows, bearing in mind the substantial downsizing of the local government workforce in the decade preceding the COVID emergency.

Among other things, the NRRP has two specific intersecting purposes: reducing the territorial disparities that characterise Italy (an overarching objective for the entire Plan) and narrowing differences in endowments of infrastructure.

With regard to the first point, at least 40 per cent of the resources envisaged under the NRRP will be allocated to the South. The resources that can be associated with projects in a specific territory total an estimated €206 billion, about 92.8 per cent of all funding (€222.1 billion) available through the Recovery and Resilience Facility (€191.5 billion) and the Complementary Fund (€30.6 billion). At least 40 per cent of these amounts, equal to about €82 billion, would therefore be allocated to Southern Italy. These resources would be supplemented by €8.4 billion from the ReactEU package and €1.2 billion from the Just Transition Fund.

The effective reduction of territorial gaps will depend on the ability of the administrative and technical units of the subnational levels of government to prepare suitable projects for the different lines of investment (bear in mind that local governing staffing has decreased significantly in the last decade) and, above all, by the ability of central government entities to guide – using public calls for proposals – the allocation of funds among entities in a manner consistent with the objectives of the Plan.

Accordingly, the PBO has considered the recent experience of implementing the Nursery School Plan to evaluate the extent to which this can provide guidance about the formulation of future calls for proposals for the implementation of the NRRP, including any corrections to be made to the criteria used for resource allocation.

The 40 per cent rule should be applied in a context in which the implementation of public policies is clearly oriented towards the identification of priorities and specific objectives, capable of selecting the projects that best meet these priorities and objectives. This should involve a survey of needs and main territorial shortcomings through the use of micro-sectoral information sources. In reality, however, it is a challenge to consistently integrate the 40 per cent rule with the criteria for allocating resources to the various lines of action, especially if at the same time one wants to satisfactorily achieve the NRRP goals and objectives, follow an appropriate expenditure profile and structure projects to achieve overarching multi-sectoral objectives, of which the reduction of territorial disparities is one of the most important.

Two critical issues emerge: on the one hand, it is possible that the calls for proposals will involve the participation of implementing entities that does not permit the allocation of resources in accordance with the 40 per cent rule; on the other hand, it is also possible that a ranking of call participants that permits compliance with the 40 per cent rule will mean accepting projects of unsatisfactory quality at the time of their evaluation, which could lead to implementation difficulties. It is therefore necessary to provide technical assistance, in a manner yet to be defined, to the implementing local authorities in order to not only encourage their participation but also to ensure an adequate level of project quality. This support may also involve strengthening the technical skills of existing personnel, so as to enable access to funding for entities that have historically demonstrated shortcomings in planning and in the use of resources.

With regard to the second point, namely the reduction of disparities in the infrastructure endowments of the different territories, achieving this objective requires strong political and methodological coordination of the many tools and funds available for this purpose. In particular, the two existing funds based on seven-year cycles (the Development and Cohesion Fund (DCF) and the European Regional Development Fund (ERDF)) have been joined by three new single-cycle instruments (the Infrastructure Equalisation Fund (IEF), the NRRP and the Complementary Fund (CF)). These five instruments will channel unprecedented funding to the new programming cycle. In total, the resources for additional and special projects to reduce infrastructure disparities amount to about €156 billion, an increase of over 71 per cent compared with those allocated by the DCF and the ERDF in the cycle just ended (about €91 billion). More specifically, these comprise: €50 billion under the new DCF (until 2027); €51.2 billion under the new ERDF, of which around €24 billion from national participation (until 2027); €4.6 billion under the new IEF (until 2033); at least €40 billion under the NRRP (those allocated to the Ministry of Sustainable Infrastructure and Mobility (MSIM), without considering other ministries); and €10 billion allocated to the MSIM drawing on CF resources (until 2026). These resources are supplemented by capital expenditure, which will contribute to achieving this same goal with the resources that the NRRP and the CF allocate to other ministries (in particular the Ministry of Health, the Ministry of Education and the Ministry for the Ecological Transition).

However, critical issues remain. The survey of both State and local government infrastructure is an essential prerequisite for assessing and reducing the territorial divide in existing infrastructure endowments and for using the variety of resources available in the coming years in the most efficient way. The very stringent mechanism and schedule established in the Infrastructure Decree , however, could lead to highly uneven assessments in the absence of adequate operational guidelines set out in advance for the various levels of government.

In order to best exploit the ample financial resources available through the five channels noted above, their coordination during all phases is of strategic importance, ranging from the general lines of action to the choice of projects to be financed, progress monitoring and entry into operation. Although the need for coordination is a key point that affects all projects, it is especially important for capital expenditure because errors and imprecision in laying the foundation of the works are difficult to reverse. The theme of coordination has already arisen during past programming cycles in relations between the DCF and the ERDF and, within the European framework, in those between the ERDF, the European Social Fund and the Territorial Cooperation Programmes. However, the issue now deserves even more attention because such coordination must be achieved among an even larger number of funds managing much larger resources, each with specific governance arrangements and restrictions on use.

The evaluation of how to optimise coordination should also consider the three funds created with the Budget Acts for 2017, 2019 and 2020, which, while not having explicit territorial equalisation objectives, also seek to revive infrastructure investments, cover the same time horizons and, above all, have total resources of almost €111 billion.

Another important aspect is the management of the resources earmarked for South. As noted above, at least 40 per cent of the resources available under the NRRP are reserved to this macro-area. The DCF, which finances part of the projects included in the NRRP, provides for an 80 per cent reserve. It is not yet clear how the coexistence of these two criteria will be managed and, above all, how it will operate for existing investments financed with the NRRP and the DCF.

Finally, to ensure that the two sides of equalisation (current resources and infrastructure endowments) do not continue to operate independently of each other, consideration should be given to including representatives of the Technical Commission for Standard Requirements on the Partnership Agreement Oversight Committee. The experience of the federalist debate of the last twenty years teaches us that, on the one hand, the equalisation of current resources for the provision of essential levels of services remains incomplete if an area does not have adequate service delivery capacity (take the case of nursery schools) and, on the other, that infrastructure deficits affect the efficiency/effectiveness of the production of public goods and services, increasing the operating costs that the current resources delivered through the equalisation mechanism seek to cover.