The Working Paper (in Italian), produced as part of a collaborative initiative between the Italian PBO and IRPET, provides a quantitative analysis ‑ both descriptive and inferential ‑ of temporal efficiency in the construction of public works in Italy. More specifically, it provides an explanation of the duration of construction projects on the basis of their main characteristics at the level of lot, contracting authority, territorial area and contractor. To this end, PBO and IRPET, using a dataset that integrates the Open Data system of ANAC, the Open Cohesion database and the Public Administration database (BDAP), developed an econometric model that provides useful insights to help assess possible critical issues associated with the actual implementation of the investments financed with the resources of the NRRP and the Complementary Investment Plan (CIP) and, above all, the choices that have to be made in the next six months in drafting the legislative decrees implementing the enabling law for the reform of the Code of public contracts (Law 78/2022) recently approved by Parliament.

The enabling Law 78/2022seeks two goals: to permanently incorporate into the Code of public contracts many of the exceptions introduced in recent years concerning public investments , and to repropose a number of measures already provided for in the 2016 Code but never implemented. The former goal includes the expansion of the scope for using direct or negotiated contract award procedures (which were very limited in 2016 in order to encourage open tenders), a renewed interest in integrated procurement (previously almost never used in practice), a broader scope for using price as the sole award criterion (in 2016 this was viewed with suspicion, with the “most economically advantageous bid” adopted as the norm), and the promotion of participation in public works by micro- and small enterprises and local businesses. The latter goal includes the introduction of a rating system for companies participating in tenders, the rationalisation of contracting authorities while enhancing their technical and management quality, and the rational and methodical subdivision of projects into lots to be tendered.

The following provides a summary of the main findings of the PBO-IRPET study regarding these aspects.

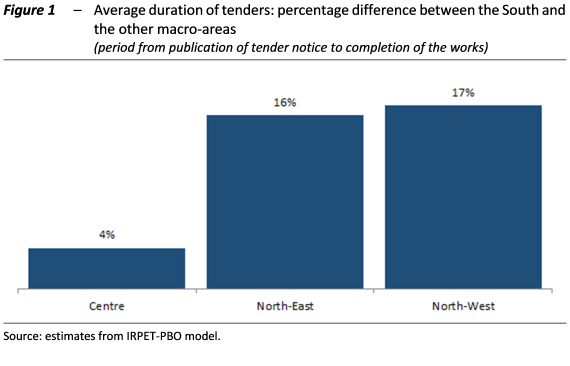

The territorial divide. – Public works procedures differ significantly between territories and between government entities. Taking the entire process from the publication of the notice of the tender to the completion of the works, the duration of projects in the South is on average 4 per cent longer than in the Centre, 16 per cent longer than in the North-East and 17 per cent longer than in the North-West (Figure 1).

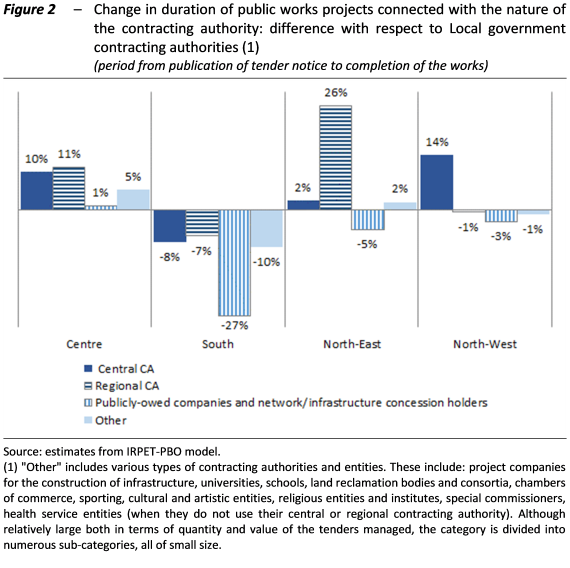

The contracting authorities of local governments, largely municipalities, perform very well in the Centre and the North compared with the central/state-level contracting authorities, regional contracting authorities and the contracting authorities of publicly-owned companies and concession holders for the operation of networks and infrastructure (Figure 2). Conversely, in the South it is always better if the contracting authority is not a local entity, so as to shorten the time needed to complete works by an average of 8 per cent if a central/state contracting authority is involved, by 7 per cent if the contracting authority is regional and by 27 per cent if publicly-owned companies and network and infrastructure concession holders are allowed to operate as contracting authorities in their specific areas of responsibility. In all likelihood, at the basis of this difference is the more general gap in performance (efficiency and effectiveness) between the public administration in the Centre-North and in the South or the more complex institutional context in which the latter operates.

Funding sources. – If public works are mainly financed with European resources (as in the case of the investments under the NRRP and those connected with EU structural programmes), the overall time needed to complete projects is shortened on average by 14 per cent compared with projects funded with own resources of the contracting authority. A similar gain also emerges when the primary source of funding is Central/State government or, to a lesser extent (a reduction of 7 per cent), a Regional government. Although the differentiation by macro-area should be investigated more deeply, what emerges is a significant policy effect: the greater the institutional distance between the funding authority and the contracting authority, the more effective is the former in acting as an impartial overseer of the allocation of resources, compliance with plans and management of projects. It should therefore be no surprise that tenders funded with European resources perform best on average, given the stringent EU rules governing participation in programmes, the clear and effective structuring of calls for tender and payments in instalments subject to verification of contract accomplishment. In principle, the presence of an attentive third-party payer could also ensure better performance in terms of correspondence of the works to their design, the quality of the works and final costs. It is therefore a hopeful sign that the huge public investment effort planned for the coming years will be closely integrated within the European framework.

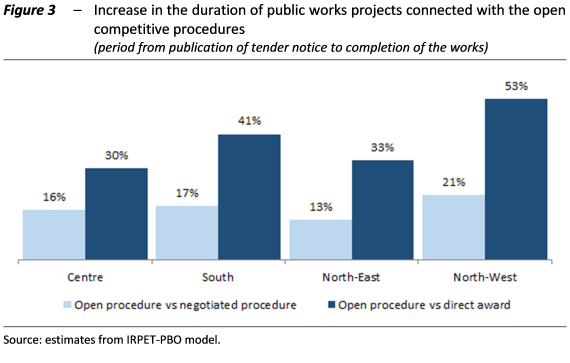

Tender format. – On average, open competitive procedures (tenders in the strict sense) tend to lengthen the overall time needed to complete works (Figure 3). Compared with negotiated procedures, the time to completion increases by 13 per cent in the North-East, 16 per cent in the Centre, 17 per cent in the South and 21 pe cent in the North-West. Compared with direct award, time to completion increases by 33 per cent in the North-East, 30 per cent in the Centre, 41 per cent in the South and 53 per cent in the North-West.

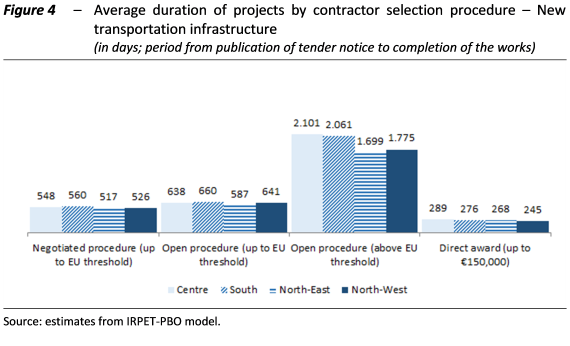

In order to provide an overview of the scale of the difference in duration across the different territorial areas in relation to project cost class and contractor selection procedure, Figure 4 shows the average expected duration based on the findings of the model in the case of the construction of new transportation infrastructure.

While the estimated average duration in the three macro-areas is virtually identical for direct awards, in the case of open procedures for works exceeding the EU threshold (€5.4 million) the difference in the average duration between central/southern areas and northern areas can be up to one year (compared with the three-year expected duration in the national average). In other words, for works above the EU threshold, the use of open procedures, which are already generally longer, can take about a year more in the Centre-South than in the rest of the Country.

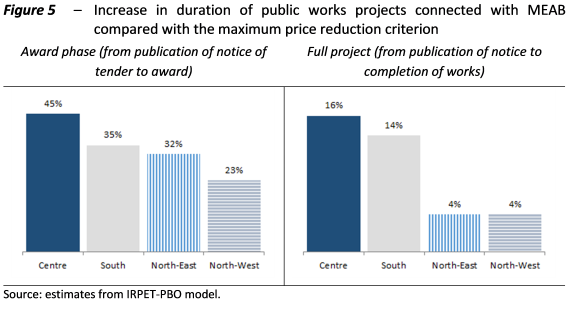

Award criterion. – It is not surprising that the use of the most economically advantageous bid (“MEAB”) – a procedure whose adoption is complex in itself, as it involves multidimensional evaluations – extends the time required to complete projects in all macro-areas compared with awards based on the maximum price reduction criterion (Figure 5). Taking the award phase only, on average the use of MEAB increases duration by 45 per cent in the Centre, 35 per cent in the South, 32 per cent in the North-East and 23 per cent in the North-West. Looking at the overall length of projects, durations remain longer but to a significantly lower degree: +16 per cent in the Centre, +14 per cent in the South, and +4 per cent in the North-East and North-West. Looking at the entire course of project implementation, in the North the increase in duration associated with MEAB appears to be limited, while it becomes appreciable in the South and Centre.

Overall, the estimates for project duration by tender format and award criterion provides evidence that simplified solutions, such as negotiated procedures, direct award and price maximum reduction, to which the enabling law reforming the Procurement Code would like to give more space compared to the 2016 reform, do not have a negative impact in terms of the overall duration of public works projects.

The advantages of open procedures and of the use of MEAB criterion can be obtained in other dimensions of efficiency and effectiveness, such as, for example, the final cost of works, the quality and duration of infrastructures, or the need for and frequency of maintenance. Within simplified selection and award procedures, optimising these dimensions would be guaranteed by the qualifications of contractors, i.e. the ex ante rating of companies participating in the tenders, and by the technical and managerial skills of the contracting authorities, both things which, not surprisingly, are key elements of the enabling law for the reform of the Procurement Code.

Integrated tenders. – The use of joint calls for tender for the design and execution of works enables execution times at the national level to be shortened by about 8 per cent compared with the use of execution-only tenders (in which the design contract was awarded previously in a separate tender). This can be reasonably attributed to greater correspondence between the demands of the project and the capabilities of the contractor. Being focused on the duration of projects, this study cannot investigate the reasons on the basis of which the Parliament has limited the use of integrated tenders in Italy in recent years, or the risk of granting excessive discretion to contractors in drawing up projects or fostering the concentration of the market in the hands of a few large operators. Within the new regulatory framework that the enabling law intends to implement, the positive effects of integrated tenders will be supported (and, conversely, the adverse effects limited) by the rational and adequate division of projects into lots (especially in the case of large projects), by the ex ante rating of companies and by the enhancement of technical-managerial capabilities of contracting authorities, which will have to be reduced in number but become more specialised.

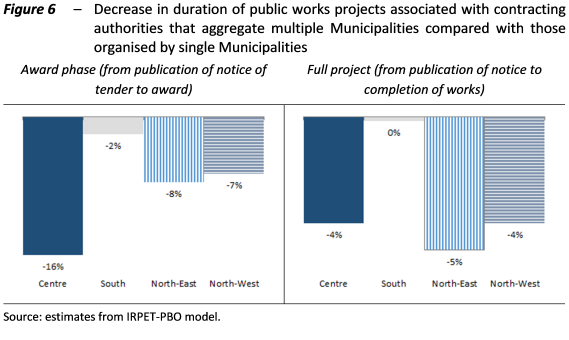

The size of the contracting authority. – In the Centre, works undertaken by large contracting authorities, such as the Single Contracting Centres, the Unions of Municipalities or Mountain Communities, take less time on average (-16 per cent in the award phase and -4 per cent for full projects) than those organised by single Municipalities. This advantage is more than halved in the North for the award phase (-8 per cent in the North-East and -7 per cent in the North-West) and substantially identical for the full project phase from the publication of the tender notice to completion of the works. The South is again the outlier, where the estimate shows a minimal benefit in the award phase (-2 per cent) and no benefit for the full project (Figure 6).

The evidence suggests that in the South the process of transformation from municipal contracting authorities to larger-scale authorities (one of the objectives of the enabling legislation) requires careful supervision from above and cannot simply take place through the spontaneous and free aggregation of entities that, on average, already struggle with organisational and planning difficulties.

The experience of the contracting authority and the successful tenderer. – The study uses the total value of works completed in the previous four years as an indicator of experience, both for the contracting authority and the contractor. The estimates appear to confirm that an increase in experience has a significant impact in terms of reducing both execution times and the overall time necessary to complete a project (from preliminary award to delivery). For both the award phase and the full project, moving from the first to the second tertile of the distribution of the experience indicator for contracting authorities reduces project duration by 6 per cent, while moving from the second to the last tertile produces an additional 3-per-cent decrease. Similarly, moving from the second to the third tertile of the distribution of the experience indicator for contractors is associated on average with a 2-per-cent reduction in project duration.

The origin of the successful tenderer. – In the central Regions of the Country, contractors originating outside the Region perform better (-8 per cent) than contractors based in the Region. This advantage persists in the North, although it is statistically less significant, but disappears in the South. This pattern deserves more analysis. The guidelines of the enabling law seek to promote local businesses by facilitating the participation in tenders of local micro-, small and medium-sized enterprises, in line with the provisions of the EU Small Business Act. Part of the 2016 reform moved in the opposite direction, however, favouring the full opening of local markets by giving preference to competitive procedures in order to support the choice of the best operators regardless of origin and dimension and to reduce/eliminate possible sub-optimal locally-rooted equilibria.

The estimates would seem to support the approach followed heretofore (and accepted by 2016 Procurement Code) and, accordingly, highlight possible issues with the overly mechanical implementation of the Small Business Act. From this point of view, business ratings will also play an important role in reconciling two otherwise potentially conflicting objectives: on the one hand, involving the local business system as much as possible, facilitating the transmission of the effects of public spending to the territory and, on the other hand, ensuring the selection of the best contractors regardless of their origin and dimension.

General remarks. – The joint PBO/IRPET analysis confirms that a number of aspects of the special legislation adopted to ensure the completion of projects financed under the NRRP and the CIP – which the recent enabling law seeks to permanently incorporate within the new Procurement Code – contribute to achieving the goal of reducing the time required to complete public works projects. Achieving this objective is a matter of particular urgency in the South, which must make up its historical infrastructural deficit with the rest of the Country and whose project completion performance is worse than in the Centre-North.

The analysis also confirms the positive effect of a generalised increase in the technical-managerial capabilities and experience of contracting authorities and contractors in reducing project completion times. The measures that are being adopted appear to be designed to encourage this factor, focusing renewed attention on the system for qualifying contracting authorities and on company ratings, which are expressly included in the agenda set out in the enabling law for the reform of the Procurement Code.

At the same time, two problematic issues must be considered. Everywhere except in the South, Local authorities registered good performance in terms of the duration of projects compared with other contracting authorities. Improving performance in the South would require the involvement of a national contracting authority, or in any case a contracting authority external to the local territorial area. The involvement of local contracting authorities, on which the NRRP is relying for the rapid activation of a large portion of infrastructure expenditure consisting of small projects spread across many territories, must be prepared and monitored appropriately, especially in the South.

Finally, although today attention is focused primarily on the duration of public works projects – because the priority is supporting economic recovery and a rapid infrastructure renewal as fundamental NRRP targets– we must not neglect the other dimensions of the quality and overall cost of the works if we are to optimise infrastructure spending in general. Even if not explicitly addressed in this analysis, these dimensions remain essential, and it will be necessary to devote a correspondingly significant amount of attention to them in both the technical and institutional debate.