The President of the Parliamentary Budget Office (PBO), Giuseppe Pisauro, sent a memorandum (in Italian) concerning the bill ratifying Decree 18/2020 (the “Cure Italy Decree”) for consideration by the Senate Budget Committee. The memorandum examines the main measures contained in the legislation and the beneficiaries affected by the measures, a preliminary estimate of their macroeconomic impact and the effects on the main public finance aggregates.

The macroeconomic impact. – The Decree activates resources equal to around 1.1 percentage points of GDP, of which more than 96 per cent (about €19.5 billion) on the expenditure side. The goal is to support the finances of households and businesses, to counter the ongoing decline in income, but also to prevent bankruptcies and layoffs that would impact potential growth.

According to a simulation performed with the macroeconometric model in use at the PBO (MeMo-It), the provisions of the Decree Law would support to the Italian economy in 2020 by almost half a percentage point of GDP. On the expenditure side, the expansionary effect would manifest itself both in consumption (public and private) and to a greater extent in investment. These impacts would be partially eroded by the increase in imports, induced by domestic demand, while there would be no appreciable effect on exports. Since the scale of this measure is limited to just over 1 percentage point of GDP, the effects on inflation would be modest.

The impact multipliers could be even higher than those indicated here, due to the current adverse cyclical conditions. As already observed following the global financial crisis of 2008, during deep recessions the liquidity constraints of households and businesses grow and the unused capacity of firms that are not forced out of business increases. In such conditions, the impact multipliers of expenditure tend to be larger than those normally estimated linearly on the basis of average historical data. In the case of this recession, which is also characterised by temporary restrictions on business activity, the capacity of closed-down companies is not relevant, however fiscal stimuli may limit business failures, which would weaken the future recovery.

Financial effects. – In 2020, the measures envisaged in the Decree will cause a deterioration of €19,959 million in net borrowing of the general government and one of €24,786 million in the net balance of the State’s budget. Over the following two years the effects are substantially nil.

Overall, uses (€20.7 billion) are only slightly greater than the deterioration in the balance, since the resources raised with the Decree are minimal (€0.8 billion). The latter are largely composed of revenue increases (€553 million) induced by the greater spending financed by the Decree itself: in fact the increase in tax and social security revenues caused by the rise in personnel spending amount to €426 million. These are accompanied by almost €127 million in revenues (mainly tax revenues) attributable to the rule that grants preferential treatment for the transformation into tax credits of deferred tax assets (DTAs) relating to impaired loans assigned within a year.

On the uses side, the Decree authorises an increase of almost €19.8 billion in spending – two thirds of which are of a current nature – and a decrease of about €930 million in revenue. Part of the measures (a net increase of more than €3 billion in spending) are targeted at the healthcare emergency, while the other provisions are intended to contain the recessionary pressures triggered by the spread of the epidemic.

Healthcare interventions. – The measures in the bill envisage an increase of around €3.1 billion in spending. The National Healthcare Fund is being expanded by about €1.4 billion, €1 billion of which for medical personnel, while a further €1.65 billion have been allocated to the National Emergency Fund (a chapter of capital expenditure whose initial appropriation was set at €685 million in the 2020 Budget Act).

Expenditure of €760 million has been authorised to pay for non-permanent personnel during the emergency period, or in any case for 2020. An additional €250 million are earmarked for increasing overtime. The increase in the funding of the National Health Service (NHS) is also intended to strengthen assistance networks, through contracts with private firms for the purchase of services (€240 million) and the requisition of private healthcare facilities (€160 million). The National Emergency Fund will provide €185 million for the purchase of ventilators and €150 million for requisition of medical equipment and other movable and immovable property. In addition, the resources will be used by the Civil Protection Department and by the special commissioner appointed to handle the emergency response to acquire any necessary resources and other activities aimed at dealing with the emergency.

At the end of the emergency the question will arise of a general structural reorganisation of the NHS and the restructuring of staffing requirements, using lessons learned to consolidate the capacity to handle ordinary demand conditions while ensuring room for manoeuvre in managing unexpected epidemiological crises.

Measures for the labour market. – The labour market measures represent the largest part of the overall package (a total of €8 billion) and are divided into a series of provisions designed to extend the social safety net and other income support mechanisms to most of the workers affected, regardless of the sector to which they belong, the dimension of the firm and the form of their employment contract.

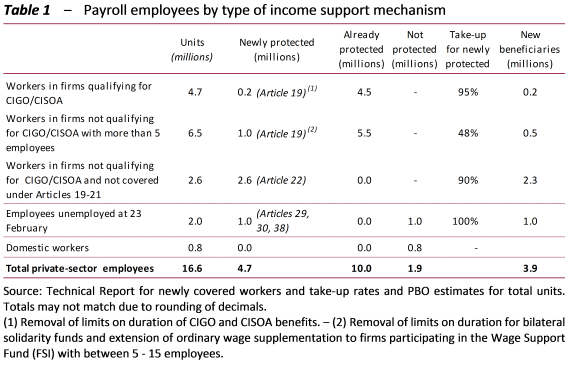

For employees, the Decree Law supplements existing income support tools, simplifying many of their requirements concerning sectors, company size and limits on use and introducing, for a specified period of time (nine weeks), new forms of protection to face the crisis. Table 1 provides an overview of private employees protected and not protected from the risks connected to the COVID-19 epidemic by old and new income support mechanisms. Private-sector employees are broken down by type of income support to which they have access. The first column shows the total number of employees in millions and the subsequent columns break down the categories by those already covered under pre-Decree legislation and the additional workers covered under the new rules, adjusted for the different take-up rates indicated in the Technical Report. The total of 16.6 million private-sector employees can be divided into approximately 4.7 million workers covered under the ordinary wage supplementation system (CIGO) and that for agricultural workers (CISOA) (insured although not necessarily recipients) and 9.1 million workers not covered by these instruments (the uninsured), further divided into 2.6 million employees of firms with up to 5 employees and 6.5 million employees in firms with more than 5 employees. Separate consideration is given to about 2 million casual workers who, based on specific estimates developed using historical INPS administrative micro-data, were not employed at the reference date indicated in the Decree (23 February). Finally, these workers are joined by about 800,000 domestic workers who do not qualify for CIGO/CIGS.

Overall, as a result of the new benefits – income support mechanisms previously not accessible and allowances for March – introduced with the Decree, about 14.7 million people (about 90 per cent of total private-sector employees) would be covered by some form of protection from the risks connected with the COVID-19 epidemic. The following categories would not be covered: 1) domestic workers, for which the Decree allows for a suspension of deadlines for the payment of pension and social security contributions and premiums for compulsory insurance and, in all likelihood, will benefit of the possibility of receiving the allowance to be paid out of the Emergency Income Fund; 2) about 1.1 million casual workers not employed at the beginning of the epidemic and not belonging to the sectors specifically protected with the fixed allowance of €600. However, bear in mind that part of the latter may already qualify for unemployment benefits (around 15 per cent) and that this category includes many who normally work for a very limited part of the year (about 70 per cent work for a maximum of three months). The former, in the event of a job loss and if they meet the requirements, could qualify for the NASPI unemployment benefit scheme or, even in the event of a suspension of work, could be eligible for the allowance payable by the Emergency Income Fund. The latter, i.e. unemployed casual workers, could, within the existing income support system, meet the requirements for the NASPI or DIS-COLL unemployment mechanisms. Finally, people in both categories could meet the requirements, which are restrictive and also consider property holdings and household characteristics in determining eligibility, for participation in the Citizenship Income scheme.[1] In this unprecedented emergency situation, it might be appropriate to consider the possibility of temporarily making these eligibility requirements less stringent so as to make an existing ready-to-use programme immediately accessible to those who have suffered or will be affected by the economic effects associated with the epidemic and do not qualify for other benefit schemes. Consideration might also be given to the possibility of extending the periods for which benefits under the NASPI and DIS-COLL schemes can be received in the event of involuntary job loss.

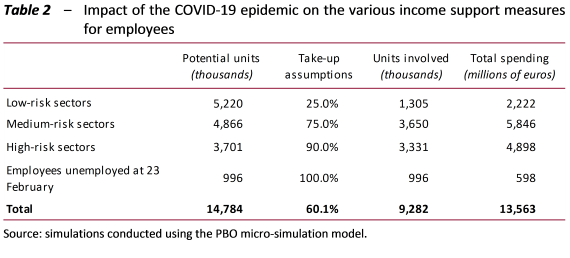

An analysis was conducted using the PBO microsimulation model to quantify the overall cost of the income support payable under pre- and post-Decree legislation in connection with the impact on the economy of the COVID-19 epidemic. This assessment is obviously highly uncertain owing to the unknowns concerning the duration and intensity of the epidemic and is based on the information available to date.

It is reasonable to assume that economic activity has been and will be affected asymmetrically in the various sectors and, therefore, the analysis refers to a scenario in which recourse to income support measures is heterogeneous. Taking a monthly benefit payment as a reference (a sort of numéraire), the take-up rate is assumed to differ as follows: 90 per cent for the sectors most affected by the restrictions (tourism, long-distance transport, education, recreational services), 25 per cent for those least affected by the restrictions (food, chemicals, pharmaceuticals, energy, gas-water-electricity supply, agriculture, financial services, retail food trade, healthcare, etc.) and 75 per cent for the remaining manufacturing sectors. In this scenario, the average take-up of the income support tools is equal to about 60 per cent, lower than the average given in the Technical Report (equal to just over 80 per cent, with differentiation between tools but not by sectors).

Table 2 summarises the results of this simulation scenario with sectors segmented by degree of risk (high, medium and low). The cost comes to around €2.2 billion for the less affected or low-risk sectors (1.3 million employees who receive a month’s benefits), €5.8 billion for medium-risk sectors (3.7 million employees) and €4.9 billion for the highest-risk sectors (3.3 million employees). In addition to these benefits, the figures must include the income support benefits for seasonal workers unemployed as at 23 February (whose take-up rate has not been evaluated, as the benefit is awarded regardless of sectoral crisis conditions), which is worth approximately €600 million for the approximately 1 million workers involved. The overall cost for the income support measures pre- and post-Decree Law 18/2020 would amount to about €13.5 billion, which is obviously susceptible to change depending on the evolution of the epidemic.

Based on the assumptions made, some €4.6 billion would be attributable to the introduction of the Decree (which is lower than the figure estimated in the Technical Report, reflecting the use of the smaller average take-up rate) and about €8.9 billion to the trend effect of the application of pre-Decree Law 18/2020 measures.

Given the number of beneficiaries and scale of the reductions in hours worked, if it becomes necessary to extend the restrictions and consequently the period for which income support will be paid, the expenditure connected with the measures indicated in the Decree Law would rise proportionally to the figures indicated in the Technical Report. New resources would therefore have to be raised to increase the spending ceilings and ensure support programmes could continue. Furthermore, the continuation of emergency conditions would also mean that normal expenditure for CIGO and CIGS wage supplementation (which would be of a trend nature, i.e. already possible under pre-Decree Law 18/2020 mechanisms) would rise to levels significantly above historical peaks. The estimate of the trend expenditure produced with the PBO microsimulation model compares with actual expenditure in 2018 of less than €1 billion.

The role of the Emergency Income Fund for workers harmed financially by the epidemic must be delineated more completely. Based on both its positioning within the context of the Decree and the small size of the appropriation (€300 million), it would appear to have a residual role compared with other income support measures. However, its essential characteristics still need to be determined with a future Decree, and it cannot be ruled out that future measures may provide for additional financing of this Fund. From the limited information provided, it would appear to be a mechanism that, should the emergency continue, would provide a subsistence benefit to those who do not have sufficient income. If the emergency were to be extended or expanded, the provision of even more generalised financial aid will be assessed, intended not only for those who see their work partially or totally suspended. The Emergency Income Fund could play the role of a faster-acting variant of the Citizenship Income, designed to support the widest possible pool of beneficiaries with eligibility being determined solely or mainly on the basis of income and on the most liquid assets held by households (which best represent immediate spending power).

As for the self-employed, the Decree Law allocates about €2.4 billion to finance an allowance of €600 paid by the National Social Security Institute (INPS) for March to self-employed holders of VAT registration numbers and persons with an ongoing working relationship with a customer, both registered with the separate pension fund (gestione separata), and to self-employed workers registered in the special funds of the compulsory general insurance system. The allowance does not form part of taxable income, cannot be combined with other benefits and is not paid to recipients of the Citizenship Income. It is also paid out regardless of the impact of the COVID-19 emergency. There is in fact no relationship between the amount of the allowance and lost income.

Estimates performed by the PBO indicate a pool of potential beneficiaries and therefore a total cost that is substantially similar to those indicated in the Technical Report: overall, just over 4 million people would be affected by the measure. The programme does not cover either those registered in the separate pension fund other than self-employed holders of VAT registration numbers and persons with an ongoing working relationship with a customer (the largest group is represented by approximately 200,000 company executive directors) or professionals registered in their profession’s pension funds: in 2018, these numbered about 1.5 million, but it is difficult to estimate those who are also registered in other compulsory social security programmes and therefore presumably recipients of other forms of income support provided for under Decree Law 18/2020.

Finally, funds of around €1.4 billion have been appropriated to cover parental leave, allowances, paid leave and vouchers for baby-sitting services. The PBO microsimulation model was used to assess the costs for private-sector employees, first simulating the use of other income support measures that cannot be combined with leave for parents of children up to 12 years of age. The benefit was attributed to 50 per cent of employees and supervisors to take account of the use of flexible working arrangements and was calculated by prudently attributing the greater between the bonus and the amount of leave for 15 days (the maximum number of days of leave). The costs estimated are substantially consistent with those reported in the Technical Report accompanying the Decree: according to the PBO estimates, employees benefiting from the leave would number around 1.15 million for a total cost of about €1.1 billion. As for self-employed workers, the Technical Report estimates a very small cost (around €50 million), considering the fact that the €600 allowance, which cannot be combined with leave, would be received by a very significant proportion of potential beneficiaries. However, it should also be considered that the assessment based on the PBO microsimulation model was produced assuming full overlap of the periods for which income support and leave are available. If this did not happen, the cost would be underestimated, i.e. if, for example, the period covered by the two measures did not coincide (a parent begins benefitting from the leave mechanism and only subsequently receives income support) or if the closure of schools were to be extended beyond the end of the period for which the parent has the right to the income support.

Measures to support businesses. – The measures envisaged in the Decree are mainly aimed at ensuring and maintaining adequate levels of liquidity. A total of €4.7 billion have been appropriated for this purpose in 2020, to which must be added the effect of a decrease in revenues due to the suspension of tax audit activities (€0.8 billion) and a number of tax incentives for expenses specifically related to the health emergency: tax credits both for the rental costs of shops and workshops for March and the sanitisation of workplaces (a total of €0.4 billion) and a tax credit for donations (€0.1 billion in 2021). On the basis of the press release on the website of the Ministry for the Economy and Finance describing the measures that were later merged into Decree Law 18/2020,[2] the liquidity and guarantee measures would provide €350 billion in liquidity and greater access to credit for the real economy.

The measures adopted to support liquidity can be summarised as follows. First, the Decree envisages measures to provide indirect support through the banking system, which mainly comprise provisions that retain and extend the operation of guarantees provided by firms to the banks, appropriating total additional resources of €3.8 billion. Second, the measures also provide for direct support in the form of tax relief for all companies in the case of the assignment of impaired receivables that can be transformed into a refundable tax credit commensurate with the presence of losses carried forward and unused ACE deductions. Finally, other measures seek to prevent tax obligations from aggravating the liquidity problems of firms. In particular, these include: the suspension, without limits on turnover, for the most heavily affected sectors of payments of withholding tax, pension and social security contributions and compulsory insurance premiums for March and April, together with the VAT payment for March; the suspension of deadlines for tax payments and social security contributions for March for firms with a turnover of up to €2 million; the deferral for firms to whom the suspensions do not apply of the deadlines for tax payments and social security contributions from 16 to 20 March; the suspension until 31 May 2020 of audit and collection activities and tax-related legal proceedings.

The measures seek to respond to the various liquidity needs. The suspension of tax payments allows firms to use the residual liquidity to meet other unavoidable costs. The incentive for the assignment of impaired receivables could provide businesses with additional liquidity through refunding/offsetting of tax credits against deductions from the tax bases (loss carryforward and the ACE) that would be difficult to use this year due to the change in economic conditions. Finally, the extension of the system of guarantees provided to banks should be sufficient to maintain adequate levels of financing through the ordinary channels of the banking system.

These measures are largely directed at firms in general, which however have been impacted, at least so far, to different extents by the restrictions imposed by the government to combat the epidemic.

It is still too early to assess whether these measures are sufficient to support businesses in coping with the COVID-19 emergency. Certainly, the scale and complexity of the crisis make it very difficult in this initial phase to support firms selectively, discriminating between the most and least affected businesses. The general nature of the measures, on the one hand, avoids the risk of excluding firms that have been harmed, but on the other hand it can lead to the dispersion of resources on firms that have so far not been directly and fully impacted by the crisis, reducing the effectiveness of the resources allocated so far. In these terms, a comparison between the firms that are suffering the most significant harm due to the health emergency and firms as a whole can provide some indication of the possible costs, in terms of lack of selectivity, of the generalised measures adopted so far.

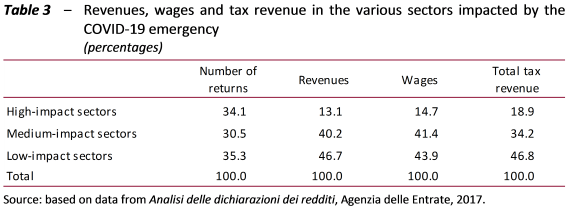

Dividing companies by sectors that have been more or less impacted by the restrictions progressively introduced in the latest decrees, we find that from the point of view of economic importance, the set of firms active in the sectors most affected by the emergency (high and medium impact) represents 53 per cent of total revenues (equal to approximately €3,400 billion) (table 3). Any contraction in those revenues (for most companies, this would involve a reduction to zero), even if only for a limited period of time, would have a significant impact on the overall liquidity of the economic system, which the provisions under consideration are attempting to address. On the other hand, these companies pay about 56 per cent of wages and salaries and contribute 53 per cent of overall tax revenue (personal income tax, corporate income tax, regional business tax and VAT). In terms of number of firms, 64 per cent of enterprises operate in high- and medium-impact sectors, with lower percentages among corporations (58.9 per cent), while 36 per cent of firms could be less affected by the slowdown in business but still benefit from the planned support measures.

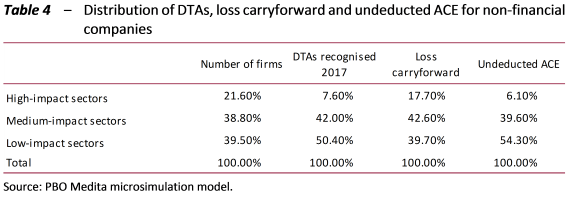

While the possibility of transforming part of assigned impaired receivables into refundable tax credits could be especially attractive for financial companies, it will also benefit companies in the non-financial sector by enhancing their ability to assign impaired positions.

With this measure, firms can reduce the cost of assigning impaired receivables – which could plausibly increase significantly at this stage of the COVID-19 emergency – in the case of liquidity requirements that could require the liquidation of even larger volumes of receivables than would be necessary in ordinary conditions. In addition, with tax credits, companies will be able to bring forward lower future taxes relating to the carry forward of past losses and the cumulative notional ACE return (amounts that with the crisis may become even more difficult to recoup in the short term), immediately gaining access to additional liquidity.

With regard to the potential effectiveness of the measure for the companies most exposed to the adverse effects of the COVID-19 emergency, Table 4 shows the distribution of DTA stocks and the deductions allowed for transformation into tax credits among the various sectors (non-financial sectors with high, medium and low impact). In this case, we find that firms belonging to the sectors that with current restrictions will experience a smaller impact from the crisis (40 per cent of the total) account for half of the DTAs recognised and over 54.3 per cent of the ACE not deducted, equal to approximately €3.2 billion.

[1] For a detailed discussion of the Citizenship Income, please see the hearing of the member of the Board of the Parliamentary Budget Office Alberto Zanardi as part of the examination of Bill 1637 containing urgent measures regarding the citizenship income and pensions – Joint session of the Public and Private Sector Employment Committee and Social Affairs Committee of the Chamber of Deputies, 6 March 2019 (abstract available in English; full text in Italian).

[2] “Protect health, support the economy, preserve employment levels and incomes. The Italian economic response to the Covid-19 outbreak” of 19 March 2020, available at: http://www.mef.gov.it/en/inevidenza/Protect-health-support-the-economy-preserve-employment-levels-and-incomes-00001/.