The Russian attack on Ukraine has had a disruptive effect on the global economy, severely impacting the short- and medium-term outlook. The April Report on Recent Economic Developments analyses the effects of the conflict on the international and Italian economies and the possible consequences of more prolonged fighting.

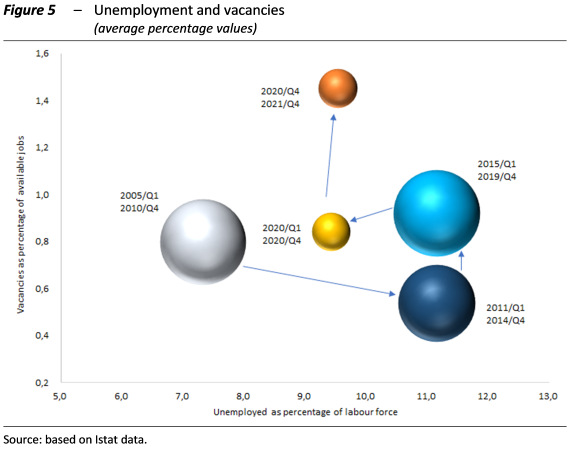

The Russian invasion sends confidence tumbling and undermines recovery. – After the sharp rebound in economic activity in 2021, the new year began with the weakening of the international economy, attributable to the rapid spread of the Omicron variant of COVID-19. The optimism that returned in February after the downturn in the case curve was swept away by the Russian invasion of Ukraine, which again altered the situation, immediately affecting commodity prices and business and consumer confidence. The global composite index of confidence of purchasing managers (JP Morgan Global Composite PMI; Figure 1) retreated to 52.7 in March (from 53.5 in February), reflecting the deteriorating outlook for exports and new production delays that have accumulated due to shortages of labour, raw materials and semi-finished products.

In its new forecasts, published on 19 April, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) revised its projections downwards for growth and upwards for inflation. The IMF expects world output to grow by 3.6 per cent this year and the next, 0.8 and 0.3 percentage points, respectively, lower than its previous forecasts. However, for the United States, the revision is just a few tenths of a point, while for the euro area, whose economies are more closely linked to the countries involved in the conflict, the downward revision for this year is more than 1 percentage point, with growth forecast at 2.8 per cent (2.3 per cent in 2023).

The conflict has already had an appreciable impact. If it continues … – With the help of Oxford Economics’ global model – Global Economic Model (GEM) – an attempt was made to both give an order of magnitude to the macroeconomic impact of the war that we can already consider established and discounted by forecasters and to the additional impacts that would be generated by the continuation of hostilities. The impacts that have already been discounted, mainly regarding increases in commodity prices, are expected to have a modest effect on the world economy as a whole but greater repercussion for Europe and Italy in particular.

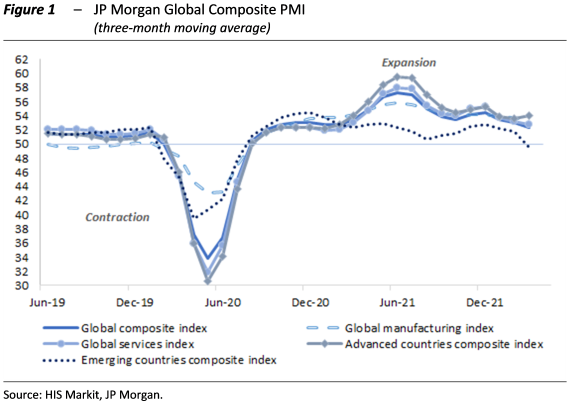

The effects of the continuation of fighting until the end of spring, with normalisation extending into the rest of the year, have also been evaluated (Figure 2). The analysis found that a longer war would cause an additional loss of GDP, with non-negligible effects at the world level and a greater impact on the euro area (-1.0 per cent). Italy would lose roughly more than an additional percentage point of GDP in 2022 and almost half a percentage point in 2023. Inflation would increase moderately at the global level, by more than half a percentage point in the euro area and by more than 1 point in Italy both this year and the next.

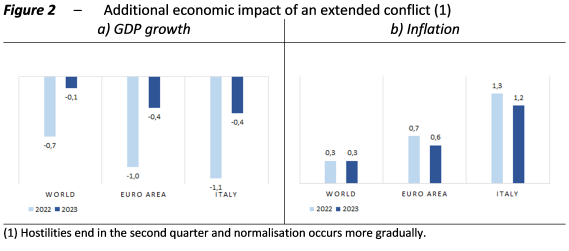

Italy, first the recovery … – Last year, Italian GDP recouped much of the unprecedented peacetime contraction registered during the pandemic in 2020. According to the annual accounts released at the beginning of March, which do not reflect the revision of GDP in volume terms issued on 4 April, output in 2021 expanded by 6.6 per cent, mainly driven by domestic demand, which contributed 6.2 percentage points. The contribution of net exports, like that of inventories, was instead only slightly positive (0.2 percentage points). On the supply side, value added rose sharply in construction and industry, excluding construction (by 21.3 and 11.9 per cent, respectively) and more moderately in services (4.5 per cent). By contrast, agriculture saw value added contract for the third consecutive year (-0.8 per cent, compared with 2020, -7.0 per cent compared with 2018).

The final quarter of 2021 registered an increase of more than half a percentage point compared with the average for the summer months, bringing the output level to just a few tenths of a point below that recorded at the end of 2019. The recovery to pre-pandemic levels is proceeding more rapidly than Germany but is lagging slightly behind France and the euro area (Figure 3).

… then the brakes. – Despite the gradual easing of pandemic-related restrictions, indicators have gradually skewed negative since the beginning of the year. In March, the first month following the start of hostilities in Ukraine, households became more cautious about purchases of durable goods, such as cars, while electricity consumption and merchandise traffic increased, suggesting that the impact of the war on all production activities could manifest itself with a lag. The difference in the initial reaction of households and firms to the war is also reflected in the climate of confidence, which last month deteriorated significantly for consumers and to a lesser extent for businesses.

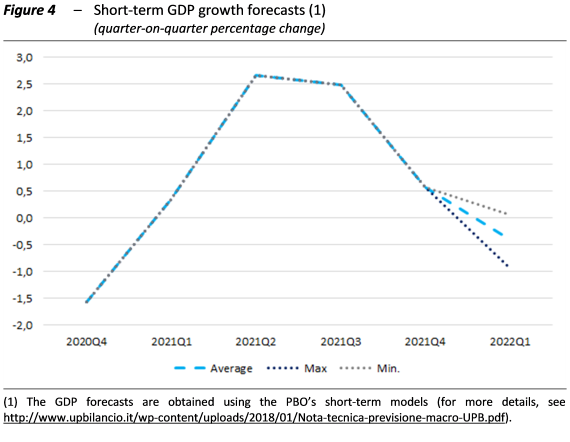

According to PBO estimates, in the first quarter of this year, GDP contracted by about half a percentage point compared with the previous quarter, with a very broad but balanced range of variation (between -0.9 and 0.1 per cent; Figure 4). The decline in manufacturing was accompanied by a more moderate weakening in services, sustained by the relaxation of COVID-19 restrictions.

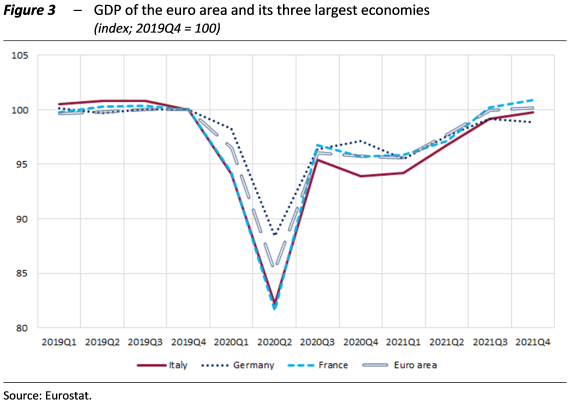

Imbalance in labour supply and demand increases. – In the first two months of 2022, the unemployment rate fell to 8.6 per cent as a result of the jump in the employment rate to a record high (59.6 per cent). The number of inactive individuals was substantially unchanged on average compared with the final quarter of 2021, when the vacancy rate rose to a record high in the major sectors of the economy, signalling a worsening of the imbalances in matching labour supply and demand (Figure 5).

Consumer price inflation reaches new all-time high. – Inflation has gradually risen due to tensions in energy markets and uncertainty linked to the Russia-Ukraine conflict, with repercussions for every link of the distribution chain. Firms and households are also revising their inflation expectations upwards towards all-time highs.

Consumer price inflation, which was still contained in 2021 (1.9 per cent), edged above 2 per cent last autumn before spiking sharply in 2022. The monthly rise in the general consumer price index (NIC) reached 6.5 per cent year-on-year in March (from 5.7 per cent in February), a level that had not been seen since 1991. Price increases are extremely common. In March, increases of more than 2 per cent involved about half of all expenditure items (43 per cent in the “core” goods group), while at the end of 2021, only one-third of items were involved.