The Focus Paper “Monitoring hospitals: financial performance and indicators of outputs, quality and outcomes” (in Italian) examines the characteristics and evolution of the main variables of hospitals’ budgets for the period 2010-2018, accompanying this analysis with an examination of information on outputs, quality and treatment outcomes for 2015-2017.

The 2016 Stability Act introduced comprehensive audit mechanisms for Hospital Authorities (HA), specifying certain parameters for financial equilibrium and the quantity/quality of services and establishing a specific methodology for calculating divergences between costs and revenues. Failure to comply with these parameters required the underperforming HA to submit a recovery plan to the regional government containing measures aimed at restoring financial balance and improve the quality and delivery of services within three years at the latest. However, this process has been hampered by the conflicting response of some regions. In fact, following an appeal to the Constitutional Court, a review of the procedures became necessary but never occurred, effectively suspending the mechanism. In the meantime, a number of HA have been removed by the regions from the scope of application of the legislation by transforming their legal form. In other regions, however, it was decided to seize the opportunity offered by the legislation to stimulate an effort to put their HA on a sound financial foundation. In some cases, the obligation to calculate the parameters needed to determine whether a recovery plan was necessary encouraged hospitals to improve the accuracy and comprehensiveness of their accounts and keep closer track of the services provided. This has made it possible to conduct more extensive and informed studies of hospitals and their performance.

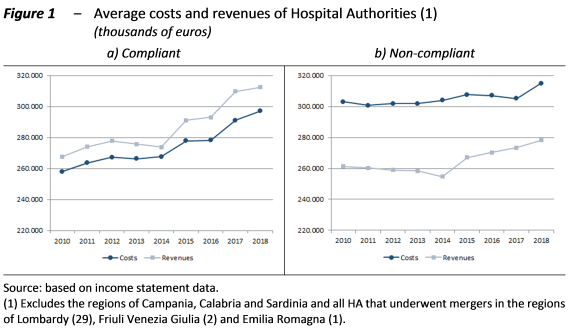

The analysis of hospital financial statements prompts a number of observations. First, the examination of the time series (2010-2018) shows that before 2015 the average deficit as a percentage of revenues, calculated in accordance with the methodology established in the legislation on recovery plans, was fairly stable, but increasing in 2014. This rise seems mainly attributable to a gradual reduction in revenues from services. Distinguishing between hospitals that in 2015 were compliant or non-compliant with the new rules, for those with excessive deficits (non-compliant hospitals) this decline began as early as 2010 (Figures 1a) and 1b)).

In turn, the decrease in these revenues reflected in part, especially among compliant HA, a reduction in grants to finance services exceeding the essential healthcare standards (EHS) and in part, especially among non-compliant HA, a decline in revenues from services subject to fees (hospitalisations, including those involving out-of-region patients, and specialist outpatient services, including co-payments since 2013). Revenue from services provided by physicians on a private fee-paying basis on hospital premises (intra-moenia) also declined, especially among the HA running deficits. On the other hand, reimbursements for pharmaceuticals (often innovative and expensive) provided to outpatients continued to rise, especially among compliant HA.

The decline in revenue may be due to the changes introduced in the national and regional fee systems, as well as to the contraction of the scope of public healthcare delivery, reflecting the combined effect of supply and demand factors. The supply side factors include the reduction in staff and beds, organisational shortcomings that made it impossible to absorb these reductions without impacting the quality of services delivered and the obsolescence of equipment connected with the lack of investment in new technologies. On the demand side, the decrease in the demand for specialist services – subject to significant co-payments, also reflecting the introduction of the so-called “superticket” of €10 per prescription – would appear to be due at first to the effects of the crisis, and subsequently to a shift in demand to the private sector.

In the hospital sector to reduce costs in an amount commensurate with the reduction in revenues is generally challenging, due to the high proportion of fixed costs and the rigidity of the factors of production. However, in the observed period, staff costs decreased in non-compliant HA, reflecting the numerous measures adopted (with a significant decrease in the headcount). The reduction in personnel expenditure partially offset the increase in purchases of goods, especially pharmaceuticals, other services and other costs. Among compliant HA, the offsetting was smaller and the increase in total costs faster.

In this phase, the reduction in hospital revenues from services subject to fees was accompanied by an increase in operating grants from the regional governments, aimed essentially at covering the budget deficits of the HA, but irrelevant for the purposes of calculating shortfalls in accordance with the methodology defined in the legislation on recovery plans.

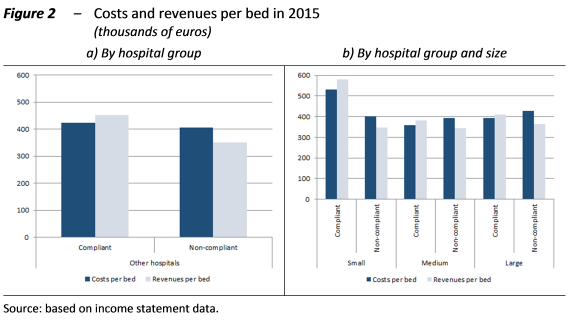

A photograph of the hospital system taken in 2015, the year in which the procedure for identifying HA that would have to draft a recovery plan was applied, shows significant differences between compliant and non-compliant HA, both in terms of the balance of costs and revenues as a percentage of revenues and the level of revenues normalised per bed. Figures 2a) and 2b) refer to Other Hospital Authorities (OHA), as in this case the analysis excludes university-affiliated hospitals integrated with the Italian NHS. The variability of revenues declines once we distinguish OHA by size, with the exception of the smaller ones (that have special features). The greater ability of compliant hospitals to attract patients may depend on the clinical specialties they offer and the relative degree of complexity, but plausibly may also depend on an insufficient overall reorganisation of the services offered and lower quality services among the group of non-compliant hospitals. In fact, the latter more frequently do not comply with the parameters for outputs, quality and outcomes and generate less revenue from transfers for out-of-region patients.

As for the costs, which do not differ too greatly between compliant and non-compliant OHA if calculated per bed, the greater weight (both as a proportion of revenues and as a share of overall costs) of staff expenditure in the latter stands out, despite the sharper drop in the immediately preceding years. In addition, small and large OHA spend less on payroll employees compared with medium-sized OHA and more on non-payroll staff.

Starting from 2015, the trends in costs and revenues change, enabling a substantial improvement in balances up to 2017, following by a slight deterioration in 2018. Compliant HA registered a rapid increase in costs, but this was more than offset by even faster growth in revenues, while non-compliant hospitals increased revenues more slowly, but managed to cut costs in 2016 and 2017. The impression that these results reflect the introduction of the legislation on recovery plans is not corroborated by evidence of the timely preparation and application of these plans at all the hospitals that should have done so, since the process was halted in many regions or proceeded slowly. However, it seems probable that the new rules in any case spurred HA to make a greater effort to avoid falling into – or to exit – the group of non-compliant hospitals, by seeking to increase output and service delivery, and, in the case of hospitals with excessive deficits, improving cost control (achieved despite a rise in staff costs). The completion of the reorganisation of a number of hospital networks may have had a beneficial impact. In the comparison between compliant and non-compliant hospitals, however, the attractive power of the former has increased in more recent years.

All this has happened against the background of an improvement in performance in terms of quality, outcomes and outputs. Nevertheless, a degree of caution is necessary in interpreting the signals transmitted by these indicators, given the difficulty of encompassing all aspects of the evaluation of the outputs and outcomes of a hospital within a small number of parameters.

The analysis contributes to understanding the state of the major Italian hospitals at the moment in which they had to face the ongoing health emergency. It represents a starting point for subsequently examining the effects of the hospital reorganisations implemented to deal with the spread of COVID-19 (especially the increase in intensive care beds and the recruitment of new staff provided for in Decree Laws 14, 18 and 34 of 2020).