The 2017 Budget Act contains measures concerning the regulation of pharmaceutical expenditure, tying part of healthcare funding to the purchase of innovative medicines and vaccines and modifying the system of expenditure ceilings and reimbursement from the pharmaceutical industry, the so-called payback mechanism. The Focus (in Italian) analyses the issue of governing pharmaceutical spending, with special attention being devoted to the ceiling mechanism and to handling budget overruns, bearing in mind the changes introduced with the budget package.

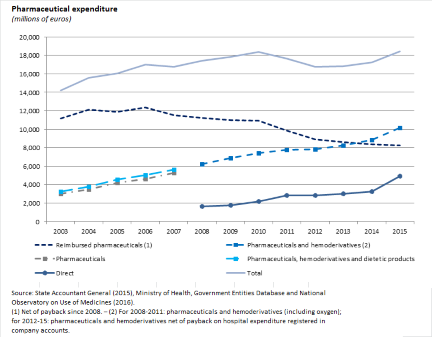

Since 2010, thanks to increasingly stringent regulation of the sector and the increase in burden sharing, the growth in pharmaceutical spending has been halted, while still finding resources for the introduction of new, expensive medicines to treat hepatitis C. The figure shows the divergent developments in purchases of pharmaceutical products and hemoderivatives and in reimbursed pharmaceuticals, due mainly to the expansion of direct distribution (with a shift in some expenditure from one aggregate to the other) as well as the introduction of innovative medicines (which are mainly registered under those purchased by public healthcare entities) and the increase in the proportion of generics (especially in the reimbursed pharmaceuticals segment).

Since 2010, thanks to increasingly stringent regulation of the sector and the increase in burden sharing, the growth in pharmaceutical spending has been halted, while still finding resources for the introduction of new, expensive medicines to treat hepatitis C. The figure shows the divergent developments in purchases of pharmaceutical products and hemoderivatives and in reimbursed pharmaceuticals, due mainly to the expansion of direct distribution (with a shift in some expenditure from one aggregate to the other) as well as the introduction of innovative medicines (which are mainly registered under those purchased by public healthcare entities) and the increase in the proportion of generics (especially in the reimbursed pharmaceuticals segment).

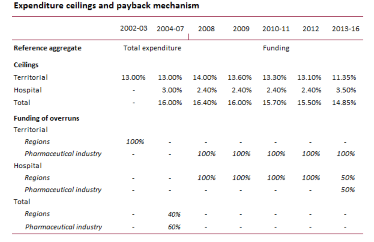

The system of expenditure ceilings and the payback mechanism has been revised multiple times. Since 2008, including measures taken as part of the spending review, the overall ceiling on pharmaceutical spending has gradually been lowered, while the pharmaceutical industry has been required to finance the entire budget overshoot of territorial spending (reimbursed pharmaceuticals plus direct purchases by local healthcare authorities). Since 2013, the pharmaceutical industry has also been required to reimburse half of any overshooting in hospital spending, the ceiling on which has in the meantime been increased by more than one percentage point.

The system of expenditure ceilings and the payback mechanism has been revised multiple times. Since 2008, including measures taken as part of the spending review, the overall ceiling on pharmaceutical spending has gradually been lowered, while the pharmaceutical industry has been required to finance the entire budget overshoot of territorial spending (reimbursed pharmaceuticals plus direct purchases by local healthcare authorities). Since 2013, the pharmaceutical industry has also been required to reimburse half of any overshooting in hospital spending, the ceiling on which has in the meantime been increased by more than one percentage point.

The application of the payback system in 2013-2015 was fraught with obstacles. Reimbursement orders were frequently appealed by pharmaceutical manufacturers and distributors, with the Regional Administrative Courts voiding many of the measures. The issue dragged on over the years, with temporary remedies, additional appeals and suspensions ordered by the courts, culminating in litigation between pharmaceutical companies and the Italian Medicines Agency (AIFA) over a payback charge of about €1.5 billion for 2013-2015, of which about €600 million has not been paid by the companies. The Regional Administrative Court is expected to issue a ruling in July.

Budget overruns by the regions were concentrated in southern Italy, Lazio and the Marche, but all regions have struggled to comply with the ceiling on hospital spending.

The challenges of enforcing the payback system have their origin in the complexity of its institutional design, a legislative framework in constant flux, the poor quality of the data used, and the inadequate soundness and transparency of the calculation procedures used by the AIFA. The main problems emerged with the aggregation of direct distribution with reimbursed medicines, which required a breakdown of purchases by healthcare units into the hospital component and the direct distribution component.

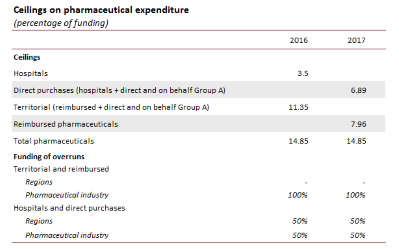

The 2017 Budget Act has aggregated direct distribution with hospital spending, rather than with reimbursed pharmaceuticals, placing pharmaceutical purchases by public healthcare entities under the same ceiling as that for direct purchases. Those ceilings have therefore been modified for the two groups, albeit with no change in the overall ceiling. In addition, the Fund for Innovative Drugs has been extended as from 2017 (it was initially limited to 2015 and 2016) and an additional Fund for Innovative Oncological Drugs was established with an appropriation of €1 billion in healthcare system resources. Both funds are exempted from the payback mechanism. Additional resources have been devoted to implementing an extensive national vaccine plan.

The 2017 Budget Act has aggregated direct distribution with hospital spending, rather than with reimbursed pharmaceuticals, placing pharmaceutical purchases by public healthcare entities under the same ceiling as that for direct purchases. Those ceilings have therefore been modified for the two groups, albeit with no change in the overall ceiling. In addition, the Fund for Innovative Drugs has been extended as from 2017 (it was initially limited to 2015 and 2016) and an additional Fund for Innovative Oncological Drugs was established with an appropriation of €1 billion in healthcare system resources. Both funds are exempted from the payback mechanism. Additional resources have been devoted to implementing an extensive national vaccine plan.

The budget measures limit the size of the payback charged to the pharmaceutical industry in 2017 and increase that for the regions: with the introduction of the two innovative drug funds, which are not included in the payback system, the expenditure ceiling is implicitly increased. By redefining the categories subject to the budget ceiling, part of the spending previously subject to the payback mechanism has been shifted to the partial reimbursement category. These effects are partly offset by the cut in the overall funding of the National Health System, which lowers the expenditure ceilings, and by the impossibility of partly mitigating the sharply rising trend in direct pharmaceutical spending (which includes a major share of spending on innovative drugs) with the moderation in spending on reimbursed medicines. The overall impact will depend on developments in expenditure and its composition between reimbursed medicines, direct purchases and hospital purchases: more specifically, the reduction in the payback will be all the greater the higher is spending on direct distribution (including outlays for hepatitis C drugs), for which the reimbursement charged to pharmaceutical companies has been cut in half.

In view of the fact that the resources, first and foremost those for the innovative drug funds, are not additional but must be found within the overall funding of the National Health Service, maintaining this approach in the future will require monitoring the balance between investment in new technologies and financing more traditional services.

The distortions in the healthcare market and the considerable market power of pharmaceutical manufacturers and distributors underscore the advisability of adopting planning measures for spending that emphasise budget ceilings and mechanisms for recouping expenditure overruns. In this framework the payback system, especially in a context of legislative continuity, would appear to be helpful, even if it cannot be the sole tool for reigning in pharmaceutical spending. Controlling the latter also requires other initiatives, such as: a revision of distribution margins, additional incentives for using drugs whose patent protection has expired or using lower cost alternatives, rationalizing the division of responsibilities between the central government and the regions with regard to reimbursement lists, planning of treatment with innovative medicines and vaccines, subject to assessment of risk/benefits and cost effectiveness, and improving the appropriateness of treatment.

The cost of innovative pharmaceuticals is becoming an increasingly important issue in the international debate, representing a challenge for policy-makers: if manufacturers are not willing to reduce prices, it has been noted that the patent system could be revised, shifting the frontier between the tasks of government (safeguarding health and, especially, health emergencies) and the operation of the market in favour of the public sector.