What is the state of Italian healthcare? The picture that emerges from the Focus Paper “The state of healthcare in Italy” (in Italian) on the eve of the approval of the 2019-2021 Health Pact, on which the appropriation of more resources for the National Health Service (NHS) depends (€2 billion for 2020 and €3.5 billion for 2021), is a study in contrasts. A number of strengths clash with problematic issues that also play a central role in the financial and policy dialogue between the Government and the regions, which has been revived after a long hiatus (the most recent Health Pact was that for 2014-2016).

The Italian healthcare system in an international comparison. – Compared with the health systems of other industrialised countries and, in particular, with European systems, the Italian NHS appears to be quite efficient and, according to some indicators, is also quite effective. Over the years, in conjunction with the adoption of financial consolidation measures, however, there has been a significant disinvestment in public healthcare, which has manifested itself through a range of deficiencies, especially in staffing levels. The contraction in resources has only partially fostered efficiency improvements and the effective reorganisation of services. This has had an impact on physical and financial access to the system, especially during the crisis, and has shifted demand towards the private market.

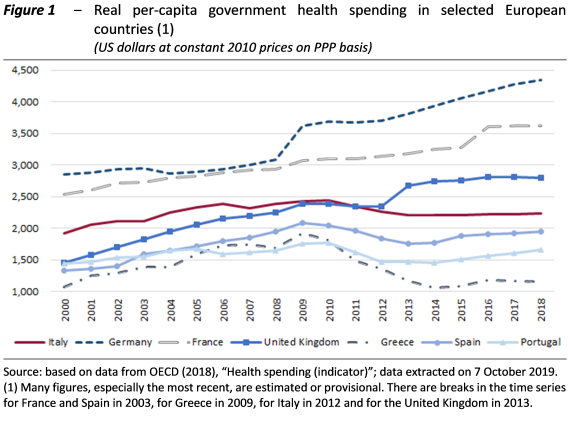

If we look at per-capita spending at constant prices (Figure 1), a slight bell shape emerges for all southern European countries, including Italy, reflecting the reduction in real per-capita resources allocated to healthcare in the years of the crisis in connection with the public finance adjustment policies adopted, which extensively impacted the health sector. There has been a partial recovery in more recent years, although the rise for Italy has been quite limited.

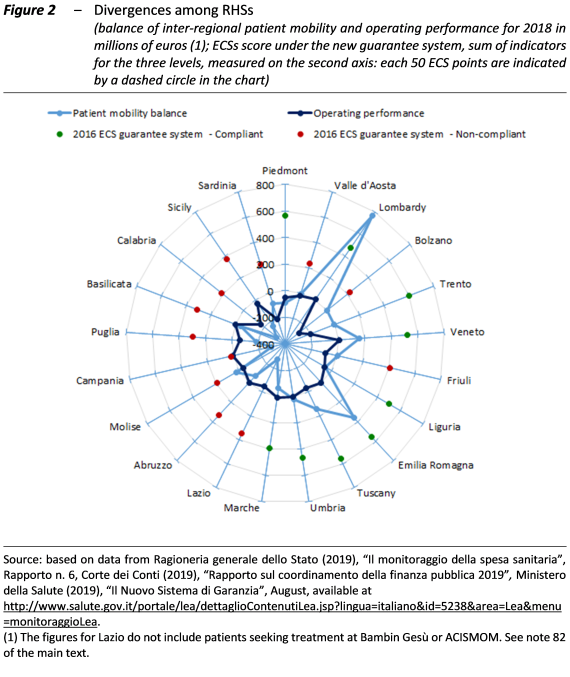

Territorial differences. – The difference in the quantity and quality of services provided by the individual regions is highlighted by various indicators. Increasingly rigid regulation and progressively more stringent central control of the management of the Regional Health Services (RHSs) were intended primarily, and successfully, to eliminate deficits. It is only with a lag that they have been directed at ensuring uniform compliance with essential care standards across the country (ECSs), and have therefore been less effective in this regard. The ability to modernise and reorganise the delivery of services has not been uniform at the regional level. As a result, apart from financial imbalances, the regions involved in a recovery plan have a high level of patients seeking care in other regions and unsatisfactory performance levels (Figure 2).

Patient mobility gives rise to a transfer of funds from the southern regions, the Marche and Lazio to other regions, first and foremost Lombardy, followed by Emilia Romagna, Veneto and Tuscany. In addition to having fewer resources to invest in their RHS, the former therefore both contribute to financing the health services (and ultimately the economic system) of the latter and to overcrowding those services.

The regions with the greatest deficits are no longer those under a recovery plan, with the exception of Calabria, but the special statue regions not under a plan (except for Valle d’Aosta), which are not required to comply with spending restrictions (also Molise and Valle d’Aosta have consistent deficits in per capita terms).

The regions that do not comply with the ECSs in accordance with the new guarantee system are all those of the South, Lazio, the Province of Bolzano, Valle d’Aosta and Friuli-Venezia Giulia. To eliminate the gap in the ability to deliver a national standard level of care, it is necessary to address – in addition to the problem of resources – the limitations (present above all in certain areas of the country) in planning, management and organisational skills as well as the capacity to resist the pressures of organised crime. At the same time, the commitment to eliminate the significant territorial disparities in the availability of infrastructure remains unfulfilled.

Health and social conditions. – Attention has recently focused on health differences connected with social conditions. A photograph of the current situation shows that in Italy the differences attributable to socio-economic factors are exceeded by those engendered by geographical differences and even more by differences emerging from the combination of social and territorial factors. The indicator for which the gaps are the most disturbing is life expectancy. Recent Istat regional data broken down by gender and level of education (a proxy of social conditions) indicate that on average life expectancy at birth fluctuates by level of educational attainment between 86.0 and 84.5 years for women and between 82.3 and 79.2 years for men. The gap between individuals with a low level of education in Campania and those with a high level of education in the Autonomous Province of Bolzano is 4 years for women and 6.1 years for men.

In recent years, significant problems have also been noted in the equity of access to services, probably also as a result of the increase in co-payments for specialist treatment, with a significant rise (at least until 2015) in the percentage of those reporting that they had forgone medical examinations for financial reasons, especially among those with low incomes.

The staffing quandary. – Spending on personnel has been among the items most affected by the restrictions of recent years. Between 2010 and 2018, despite the partial recovery in the last year of this span, expenditure decreased in absolute terms by almost €2 billion. This trend was accompanied by a reduction in the number of staff, including doctors and nurses, especially in the regions involved in a recovery plan. In 2017, the permanent staff of the NHS was about 42,800 lower than in 2008. The contraction was continuous starting in 2010 and was concentrated above all in the regions involved in a recovery plan, where since 2008 staff numbers have fallen by almost 36,700, with a decrease of 16.3 per cent for those under a standard plan and 4.8 per cent in those under a “light” plan (in ordinary statute regions not subject to a recovery plan, the reduction was 2.2 per cent; in the autonomous regions, staff numbers rose by 2.4 per cent).

In 2017, permanent employees numbered 81 per 10,000 inhabitants in the regions involved in an ordinary recovery plan, 108 in those under a light recovery plan, 119 in those not subject to any plan and 148 in the autonomous regions. The difference was not large for doctors (17 per 10,000 inhabitants for the regions under a standard recovery plan, 19 for those under a light recovery plan, 18 for those not subject to any plan and 24 in the autonomous regions), but it was larger, for example, for nurses, with a figure 35 per 10,000 inhabitants (ordinary plan) and 43 (light plan), compared with 49 (no plan) and 57 (autonomous regions).

While these difficulties have been addressed by easing spending restrictions, providing funding for new hiring and training, and allowing the recruitment of doctors who have not yet completed their specialised training, it remains a priority to strengthen training on a long-term basis, revise the mechanisms for determining personnel requirements and develop, within the constraint of budget restrictions, a response to the urgent need to alleviate current staff shortages.

Restructuring of hospital and regional networks. – The reduction in personnel has been accompanied by a sharp contraction in hospital facilities, with a goal for hospital beds (3.7 per 1,000 inhabitants) that is far below the European average, which declined from 5.7 to 5 between 2007 and 2017 (when the number of beds in Italy fell from 3.9 to 3.2).

Reducing expenditure for hospital services as a proportion of total health spending has been an explicit objective of health policy, which has sought to shift care to less expensive structures closer to the public. However, the insufficient expansion of local services is a question mark for the success of the operation, as signs of rationing have emerged, in particular in emergency services. In regions involved in a recovery plan, structural deficiencies, the presence of a strong accredited private sector, undersized facilities and the scarcity of resources make it more difficult to eliminate the reasons underlying the shortcomings and implement the necessary reorganisation measures.

The growth of the private sector. – The increase in the cost of specialist and diagnostic services with co-payments (the so-called “superticket”, which the draft budgetary bill proposes to eliminate) has concurred in the demand shift towards the private sector, with the entry of new players and the expansion of existing providers. Between 2012 and 2018, total expenditure for care and rehabilitation services (hospital, outpatient and home care) increased by 4.8 per cent: while public funding remained broadly stable (+0.8 per cent), having been curbed by the reduction in hospital spending (-2.5 per cent), direct household expenditure grew by 25.1 per cent, mainly due to the increase in the outpatient component (30 per cent), while private hospital spending declined (-1.9 per cent).

A similar effect is being exerted by tax benefits for “occupational welfare” measures. These measures foster the emergence of an alternative corporate-sectoral system as an alternative to the public systems, one that is also expanding outside the area of supplementary services (essentially represented by dentistry and long-term care). Supporting this tendency while continuing to reduce funding of the public health system could undermine the universality of current arrangements, where the transition to a mutual, or even private, healthcare system could produce an increase in overall health spending, exerting pressure on public expenditure as well.

Innovation and pharmaceutical expenditure. – In the light of the continuous introduction of expensive innovative pharmaceuticals (for which the Government has appropriated €1 billion per year), the question of the role of technical progress – now considered the main factor in increasing expenditure – strongly emerges in the management of health systems. The prices of new medicines not only reflect the cost of research, but often incorporate very high monopoly rents. To some extent these costs have been offset by the savings generated by the spread of generic drugs, which are less expensive than brand-name pharmaceuticals, but rigorous governance of the system is also necessary.

In addition to the need to bring the weight of governments to bear in the market for innovation, so that prices do not rise so high they become unaffordable for public systems, and to carefully assess the risk-benefit ratio and cost-effectiveness of new products and technologies, a long-term vision must consider technical progress, in all areas of healthcare, as an opportunity rather than as a threat to the sustainability of the system.