In recent years, turnover in the gaming industry in Italy has increased, providing a significant and growing contribution to tax revenue. This Focus (in Italian) describes the evolution of the gaming sector as a whole and of its segments (more traditional games, betting and new-generation games), focusing on the main economic and fiscal issues, also in the light of recent interventions to curb the range of gaming products to combat “gambling addiction” and so-called problematic gaming.

Developments in the gaming industry and geographical distribution. – Overall, the companies involved in the gaming sector are about 6,600 with well over 100,000 employees, 20 per cent of whom work in the direct supply chain and 80 per cent in the indirect supply chain (points of sale, tobacconists, bars, mobile homes, newsstands). In line with the expansion of the market, the turnover of the sector’s allied industries (manufacturers of games and electronic components, machinery sales, rental and equipment managers, receivers, bingo halls, gaming halls) almost doubled from 2006 to 2011, while Sisal and Lottomatica – the main players in the sector – invested several billion euros in advertising. Ultimately, gaming has established itself as a major national industry.

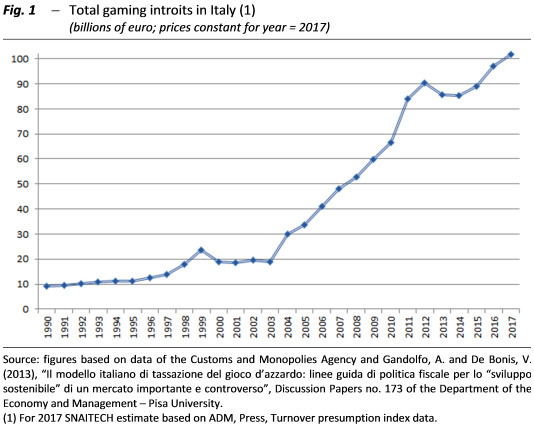

Between 2000 and 2016, total introits from gaming, an indicator of the size of the market, increased fivefold, from 20 to approximately 96 billion euros in real terms (recent estimates put total introits at more than 102 billion euros in 2017; fig. 1). In 2016, winnings exceeded 77 billion and the payout, i.e. the percentage of the funds that are on average returned to players in the form of winnings/awards, was around 80 per cent. The remaining 20 per cent, equal to an actual expenditure by players (difference between bets and winnings) amounting to more than 19 billion, was divided between tax revenues, about 10 billion (10.5 per cent of introits) and the turnover of the sector, more than 9 billion (8.5 per cent of introits).

As regards the regional distribution of gaming, two interesting pieces of information are provided by the per capita introits (i.e. the ratio between the introits and the adult population, 18-74 years) and by the ratio between the introits and the disposable income of the individual regions. The first indicator provides an idea of the intensity of gaming activities, albeit in an approximate and inaccurate manner. The Abruzzi is the region with the highest per capita introits (1,767 euro), followed by Lombardy and Emilia Romagna (1,748 and 1,668 euro respectively). In Southern Italy, on the other hand, average introits are generally lower than the overall average (1,291 and 1,475 euro respectively). The second indicator instead provides a proxy of the propensity to spend on gambling. In this case, the data show a greater propensity in the regions of the South, with a percentage of 8.3 per cent, compared to a national average of 7.2 per cent and that of the North of 6.5 per cent. In this case, the relatively higher propensity in Campania and the Abruzzi stands out (10.2 and 9.7 per cent respectively).

The expansion of the gaming sector was largely due to the strong innovation in gaming methods with the spread of the Internet and the ability to play through the network, online and on live events. Since 2002, gaming dealers have been allowed to accept bets remotely, via the Internet or the telephone network. The range of betting has increased and demand has become more dynamic. Despite the fact that the Italian legal system did not permit it, there has been a growing flow of bets to foreign bookmakers, who, operating legally in their respective countries, thanks to the Internet, could accept bets from Italy and make them flow into their data transmission networks (RTD). In 2006, therefore, a gradual opening of the Italian market began, with national legislation adapting to the requests of the European Commission to ensure principles of freedom of establishment and freedom to provide services enshrined in the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union. To date, European Economic Area (EEA) operators may accept bets from residents in Italy provided that they hold a valid Italian licence or are part of a business agreement with another Italian licensed entity.

In Italy, the organisation and operation of games and betting are reserved by law to the State and entrusted to the Ministry of the Economy and Finance, which in turn operates through the Customs and Monopolies Agency (ADM). Games are managed either directly or by granting an appropriate licence to persons who provide an adequate guarantee of eligibility.

Alongside more traditional games, associated with lotteries and betting on physical networks, which in recent years have shown a certain stability in the volume of bets and in the actual spending of players, online games and those associated with amusement machines are the ones which appear to be the most dynamic. This mode of use also exposes players to greater risks of addiction. To limit the expansion of forms of compulsory gambling, in June last year Law 96/2017 provided for an increase in tax rates and established that the 35 per cent reduction in the number of operating authorisations for new slot machines (so-called AWPs), provided for in the Stability law for 2016, should be implemented in two phases: the first, i.e. the reduction to 345,000 authorisations, was implemented by 31 December 2017; the second, i.e. the further reduction to 265,000, was regulated by managerial decree of the ADM dated 30 March 2018, the implementing procedures for which have just been set out in the subsequent managerial decree of 30 April.

Furthermore, the Stability law for 2016 provided for a more structural intervention aimed at affecting the points of sale of games to be specified, by 30 April 2016, in unified Conference between the State, Regions and Provinces. The agreement, reached in September 2017, provided, among other things, for the reduction of the points of sale and their territorial reallocation. However, although some local authorities have already begun to implement the provisions of the Agreement, the latter has yet to be implemented through a decree of the Minister of Economy and Finance, after consulting the competent parliamentary committees. This could result in a significant loss of revenue.

The taxation of gaming. – Given its economic importance, the gaming sector is a major source of tax revenue.

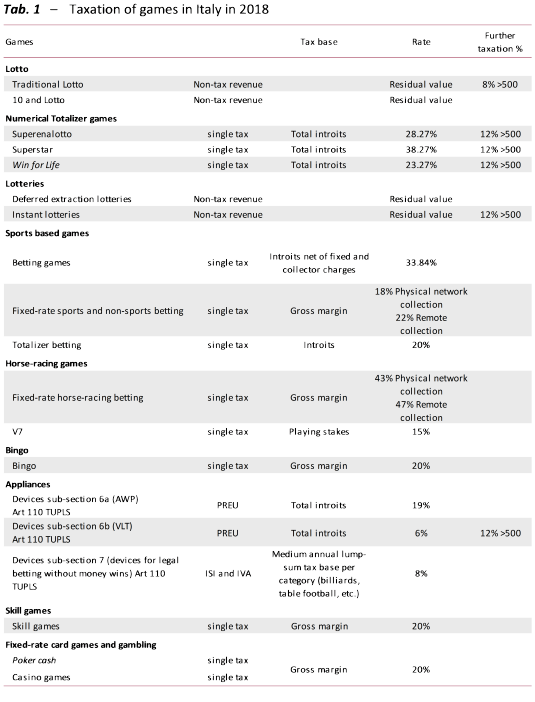

The legal framework for the collection of taxes from the gaming sector is complex, as the various types of gaming are taxed in different ways and at different rates, and the relevant legal provisions increasingly refer to decrees issued by the Director-General of the ADM. The last structural revision dates back to the Bersani Decree of 2006.

The revenues generated by the gaming sector can be distinguished according to whether they fall within non-tax[1] or tax revenues. In the first case the tax is calculated in a residual way and is obtained by subtracting from the total amount of bets (introits), the winnings paid to players and the commission due to the gaming point operator. This levy applies only to Lotto, Instant Lotteries and deferred extraction lotteries and, until 2016, to Bingo.

Revenue generated by all other games is instead classified as tax revenue. Taxable persons are the game dealers and tax bases and tax rates vary according to the different types of game. In particular, there are currently four types of rates:

- Prelievo erariale unico (PREU), established in 2003 for AWPs and videolotteries (VLTs). The tax base is represented by the introits (bets), whereas the tax rate, which differs between AWP and VLT, is generally set by budget laws, although ADM may, by means of its own decrees, issue all the relevant provisions in order to ensure higher revenue;

- Imposta unica (single tax), which applies to numerical totalizer games, to sports-based and horse racing games, distance skill games, card games, fixed odds lottery games, cash poker and casino games. The tax base is represented by either the introits or the gross margin (GGR), calculated as the difference between the introits and the premiums paid back to players. The rates vary with games and here again they can be changed by legislation or by the ADM;

- Imposta sugli intrattenimenti (entertainment tax – ISI), which applies to games in which no cash winnings are provided. In general, the tax base here is calculated on a flat-rate basis, depending on the type of game;

- VAT rate, which only applies to games for which no cash winnings are provided.

Finally, since 2012, for some types of games, an additional tax on winnings above 500 euros has been introduced, the so-called tax on luck. To date, winnings in excess of €500 for numerical totalizer games, fixed-rate numerical games, lotteries and prizes paid by the VLTs have been taxed, albeit at different rates. A summary of the different forms of taxation is shown in Table 1.

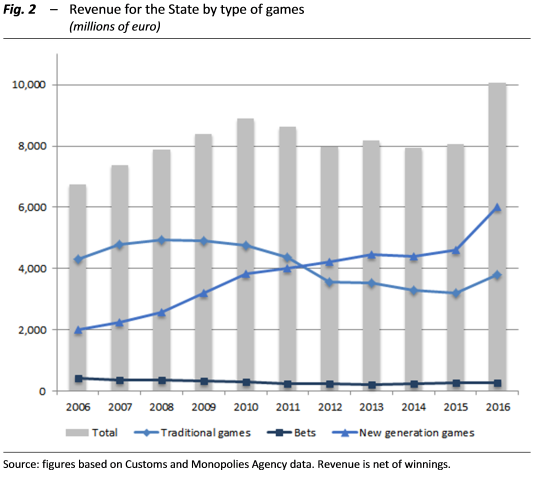

Up to 2016 (the most recent data available), the revenue of the gaming sector amounts to almost €10 billion, corresponding to 0.6 per cent of GDP and more than 2 per cent of total tax revenues. Overall revenue (net of winnings) increased significantly between 2006 and 2010, from €6.7 billion to €8.8 billion, thanks to high growth rates (above 17 per cent per annum on average) in the new generation gaming sector. Since 2011, revenue has stabilised at €8 billion, despite the sharp drop in revenue from traditional games. The peak of 2016 is due to the recovery of introits and the upward revision of tax rates (fig. 2).

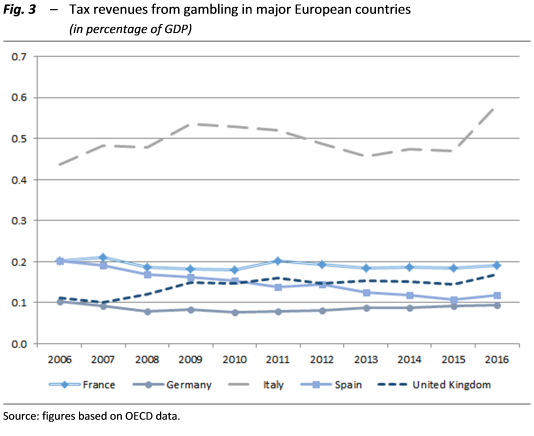

Compared to the major European countries, Italy shows a higher level of taxation throughout the last decade, with revenue (if we exclude the peak recorded in Italy in 2016) more than double that of France and the United Kingdom, and almost four times that of Spain and Germany (fig. 3).

A comparison of total introits is not possible due to a lack of data; however, if we consider the actual expenditure of players in relation to GDP, in 2015 Italy ranked first among the major European countries (0.8 per cent), after the United Kingdom (0.7 per cent), Spain (0.5 per cent), France (0.4 per cent) and Germany (0.3 per cent). Italy was overtaken by the United Kingdom only in terms of actual per capita expenditure (about €355 and €362 per year, respectively, for the adult population).

Looking at the individual segments of the gaming sector, it should first be noted that in the last decade revenues from the betting sector have remained marginal (fig. 2). The stability of tax revenues will be guaranteed also in the future by the traditional gaming sector (lotto, lotteries, etc.), which in recent years has shown substantial stability as regards introits. The betting sector, thanks to the recent change in the tax base (it is the gross margin which is now taxed and no longer the introits) and the amnesty that has recently led to the emergence of so-called data transmission centres (DTCs), could instead determine increases in revenue. On the one hand, the new taxation structure may lead dealers to increase gaming payouts, which generally leads to an increase in the volume of bets, while on the other hand the emergence of the tax base should ensure a growth in revenue in the coming years.

In recent years, revenue has also been sustained by the repeated increases in the levy applied to new-generation games (AWP and VLT). Given that demand for gaming generally shows a high degree of price elasticity, the increases in the levy and above all the planned reduction in the number of points of sale, could, in the long term, lead to a fall in overall introits, weakening the economic stability of the sector (the result of past investments undertaken on the basis of more favourable fiscal conditions for the entire sector) and causing a reduction in tax revenue.

It should also be borne in mind that the regulation of taxation in this sector is intended to protect consumers and the public interest. An increase in taxation, while not maximising revenue, allows the internalisation of the social costs caused by gambling addiction and more generally associated with gambling. On the other hand, in the context of behavioural economics it has been shown that in cases of addiction to gambling and smoking, higher taxation can positively influence the decision-making of individuals and reduce social risks.

[1] This revenue is included as indirect taxes both in the State Budget and in the General Government economic account.