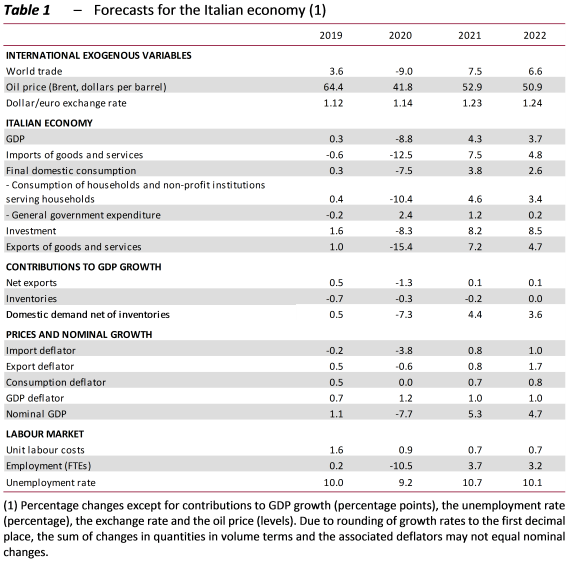

After a year marked by the COVID-19 pandemic, this year the world economy is expected to post a recovery, the strength of which, according to the February Report on Recent Economic Developments, will largely be linked to the evolution of the health emergency and the success of vaccination campaigns undertaken in the individual countries. Following the sharp contraction in GDP recorded last year, Italy is also expected to experience a recovery, although it will be weaker than that envisaged in the Update due to the downturn recorded in the last quarter of 2020 and the impact that this will have on growth in 2021. This year, GDP growth is forecast to be 4.3 per cent, while in 2022, thanks in part to the contribution of Recovery Plan funds, output is expected to increase by 3.7 per cent, returning to a level still below that registered in 2019. The medium-term macroeconomic scenario remains exposed to a number of risk factors, mainly on the downside.

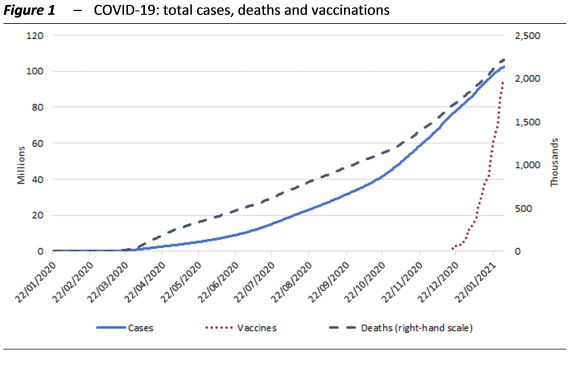

The cost of the pandemic, vaccines offer hope and unknowns – The pandemic crisis has produced heavy losses in terms of both human lives (at the end of January, the number of cases worldwide exceeded 100 million, while 2 million have died – Figure 1) and output. It is estimated that 2020 experienced the largest contraction in economic activity since the Second World War and that output will in the best-case scenario return to its 2019 level only at the end of this year. Much will depend on vaccination campaigns, which have been under way for more than a month but owing to delays in the supply of vaccines could require more time to achieve the vaccination objectives originally planned.

The second wave of the pandemic quickly impacted confidence. In Europe, the Purchasing Managers Index (PMI) has been below 50 since November, while in China and the United States it has remained above that threshold. Despite the new wave, GDP in the United States grew in the last quarter (1.0 per cent on the previous quarter) and the contraction in GDP in 2020 (-3.5 per cent) was smaller than that registered in other countries. In the euro area (where GDP fell by 0.7 per cent in the fourth quarter) 2020 closed with an overall decline in output of 6.8 per cent. In China, the economy returned to growth as early as the spring, accelerating gradually until the final part of the year: in 2020, the Chinese economy was the only one among the G20 members to record an increase in GDP (2.3 per cent).

In its most recent forecasts, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) has slightly raised its estimates for global growth this year. In 2021, world output should increase by 5.5 per cent, three-tenths of a point more than forecast last October. For the advanced economies, the revision is mainly positive for the United States and Japan, while it is negative for the euro area and the United Kingdom. The Chinese economy should accelerate sharply in 2021 (to 8.1 per cent) and return to pre-crisis levels by the end of the year. Conversely, most other economies are not expected to return to their former levels before 2022, especially in the euro area.

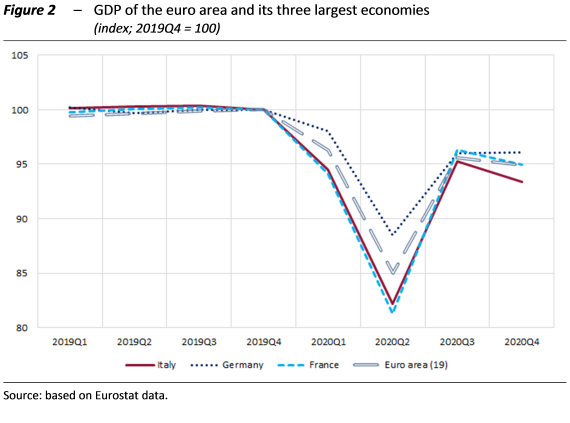

Italy: from the summer recovery to the autumn cold snap – After rebounding in the summer months, the Italian economy experienced a new slowdown in the fourth quarter in concomitance with the resurgence of the pandemic around Europe. According to preliminary estimates by Istat, Italian GDP contracted by 2.0 per cent on the previous period, a larger drop than that for the euro area as a whole, where activity subsided by 0.7 per cent, while output was virtually stagnant in Germany (Figure 2).

Based on quarterly data, the overall GDP change in 2020 compared with the previous year was -8,9 per cent (as against an increase of 0.3 per cent in 2019), the worst performance since the war. The annual accounts showed a marginally smaller decline (-8.8 per cent), due to two more working days compared with 2019 (255 against 253).

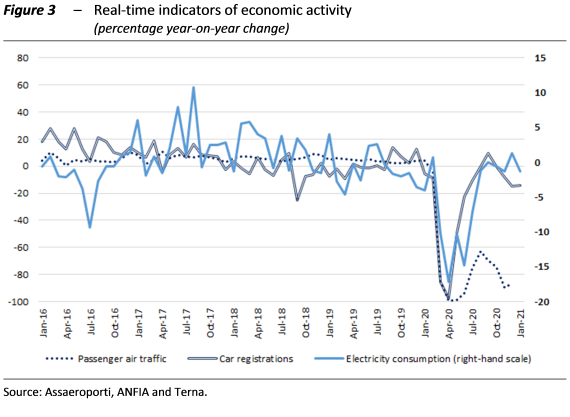

The strong but differentiated economic impact of the pandemic in the final part of 2020 was confirmed by developments in the most timely monthly variables (Figure 3): electricity consumption substantially held up in the autumn, in line with the pace of output in manufacturing, but weakened again in January. By contrast, car registrations declined sharply, reflecting prudence in consumer spending decisions. Air traffic was heavily affected by the new wave of the pandemic, not unlike in the spring.

The composite indicators of the business cycle are consistent in signalling weak activity for the beginning of this year as well. In December, the Bank of Italy’s coincident indicator of underlying growth (ITA-coin) remained in negative territory for the tenth consecutive month, albeit at just under zero. Istat’s leading indicator stabilised for the third consecutive month, interrupting the growth that began in May.

A slower recovery … – Despite the decline in GDP in the fourth quarter, the statistical carry-over impact on 2021 is positive (2.3 per cent). Economic activity is foreseen to expand again this year (4.3 per cent on average for the year). The growth is expected to emerge in the spring, taking advantage of a gradual relaxation of the measures restricting individual movement. Economic activity would also benefit from measures financed from the public budget and the Recovery Plan funds, which would also produce effects in 2022. The change in GDP in the final year of the forecast horizon (3.7 per cent) would not be sufficient to return output to the level recorded before the pandemic: GDP would remain about 1.4 percentage points lower than its 2019 level. (Table 1).

Compared with the macroeconomic scenario formulated by the PBO on the occasion of the endorsement exercise for the forecasts in the Update, the annual rates of GDP growth have been significantly revised, largely offsetting each other in the level of GDP at the end of the forecast horizon. An increase of nine-tenths of a percentage point in growth for 2020 and one of about 1 point in that for 2022 would be offset by the reduction of almost two points in the GDP growth forecast for this year.

… and risks still high – The macroeconomic scenario for the Italian economy remains surrounded by extraordinarily high uncertainty, with risks mainly on the downside. International economic conditions are linked to the evolution of the pandemic. The uncertainty of economic operators connected with the duration and repercussions of the health emergency will remain high at least until vaccination campaigns begin to have a tangible impact on the pandemic. In the short term, trade tensions between China and the United States remain a risk, as the new US administration has confirmed the policy of protecting domestic companies to the detriment of foreign firms.

For Italy, the forecasts presented strictly depend on the assumption that pandemic will gradually return under control over the forecast horizon, thanks in part to progress on the vaccination front. With regard to economic policy, it is assumed that support measures for households and firms will be continued and that Italy’s use of the European funds made available under the NGEU programme enables the launch of projects to spur development without delay. Otherwise, a new resurgence of the pandemic would prolong the health emergency, with a tightening of measures to limit individual movement and negative impacts on spending decisions and economic activity. Similarly, the partial, delayed or inefficient implementation of investment projects under the National Recovery and Resilience Plan would undermine an important source of support for economic activity.

Expansionary fiscal and monetary policies are reducing the severity of the recession in various countries by expanding the balance sheets of governments, central banks and international financial institutions. In the coming years, once the virus has been brought under control and the world economy returns to stable growth, the high level of debt accumulated will need to be reduced. Mismatches in cyclical conditions in different countries could affect the sovereign risk premiums demanded by financial markets for economies where recovery is slower. If this eventuality should concern Italy, which already had a large stock of public debt, financial tensions could be reflected in a sudden deterioration.