The challenges for the Italian economy are increasing on multiple fronts. According to the October Report on Recent Economic Developments, GDP growth may have turned slightly negative in the third quarter, while inflation continues to rise and the uncertainty of households and firms has begun to intensify again. All of these developments are occurring in an increasingly challenging international environment; the impact of the war in Ukraine is becoming more severe each month, as hostilities continue and threatens to undermine the growth outlook for the world economy.

War and inflation weigh on the global economy and push Europe to the brink of recession

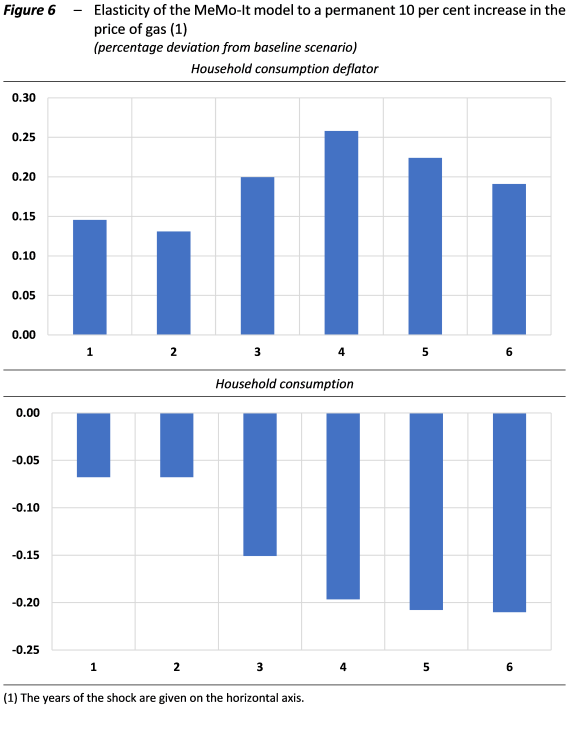

Since the outbreak of the conflict, the rise in the prices of energy raw materials accelerated dramatically, driving inflation in the euro area to almost 10 per cent in September (from 2 per cent in July 2021). In the United States, on the other hand, inflation has begun to display initial signs of a reversal, although it remains very high (8.2 per cent in September). In the first seven months of the year, developments in international trade displayed a fluctuating pattern, recording four negative and three positive changes, with expectations of a weakening in the final part of the year (Figure 1).

The International Monetary Fund has recently revised its growth forecasts for the world economy downward for next year to 2.7 per cent (-0.2 percentage points compared with last July). The cut in the growth forecast for the euro area was much sharper, going from the 1.2 per cent projected in July to a modest 0.5 per cent.

The uncertainty of households and firms continues to intensify

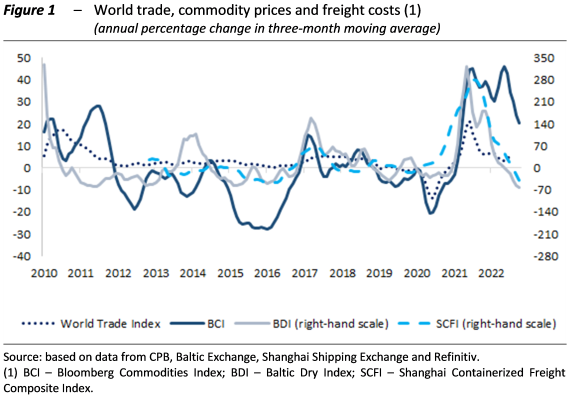

The views of firms and households concerning economic activity and inflation are deteriorating rapidly. In the summer, the uncertainty of households and firms, as measured by the indicator developed by the PBO, increased again reaching levels close to those seen during the sovereign debt crisis of 2012-2013 (Figure 2). The evidence supporting this change in the economic climate is plentiful. In July-September, electricity consumption slumped sharply in seasonally adjusted terms, returning to levels close to mid-2020. The consumption of gas for industrial uses also continued to decline, reflecting the lower industrial activity induced by inflation. Following a slight upturn in the spring, new car registrations fell in August-September, remaining well below the levels posted at the end of 2020.

Italian GDP growth hits the brakes: -0.2 per cent in the third quarter according to PBO

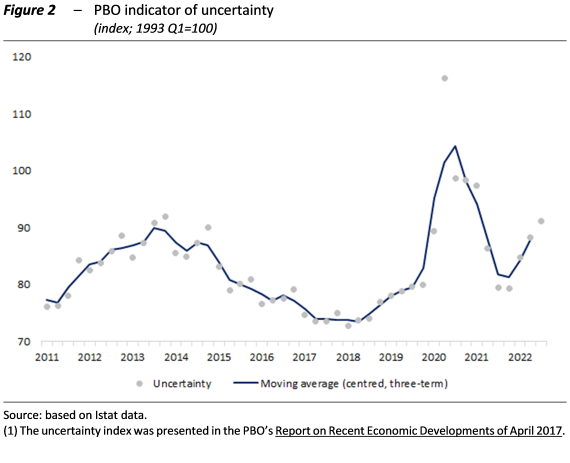

According to the PBO estimates, Italian GDP contracted by 0.2 per cent last quarter, after having posted a rebound in the second quarter (Figure 3).

The downturn in industry and construction was offset by the resilience of services, although the latter are beginning to struggle with the rise in the cost of transport and recreational activities. In the fourth quarter of 2022, the situation could deteriorate further due to inflation and the persistent consequences of the conflict in Ukraine. However, thanks to the strong performance registered in the first half of the year, the 2022 should close with a growth of 3.3 per cent. By contrast, in the PBO trend scenario, GDP should slow down significantly next year, with only a modest expansion (0.3 per cent). The uncertainty of the forecasts for 2023 is nonetheless very high, because developments in the next few months depend heavily on geopolitical factors, such as the war in Ukraine, and on the impact on expectations.

Inflation is not slowing and is now affecting household spending

Inflation in Italy continues to be primarily fuelled by tensions in the energy markets, but the price increases are spreading downstream along the distribution chain, also on the less volatile items, with an ever greater impact on the so called “shopping basket”.

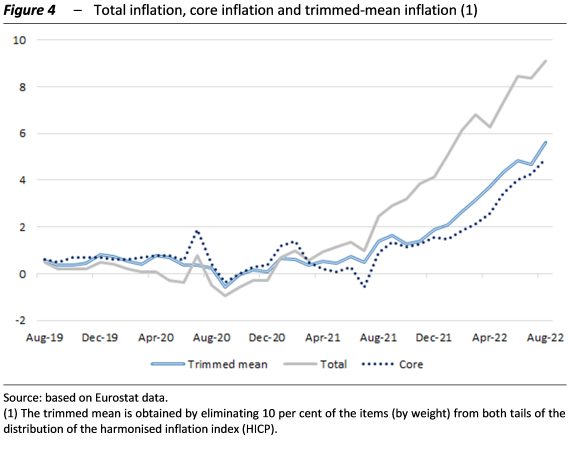

Excluding expenditure items that have registered extreme variations (the lowest and highest 10 per cent of the distribution) produces a measure of core inflation known as trimmed-mean inflation, which in August approached 6 per cent (Figure 4). The increase in core inflation amplifies the risks that inflation will remain persistently high, as shown by the forecasts of market analysts, which are congregating around ever higher values along the distribution curve.

The rise in consumer prices is eroding household purchasing power, despite the significant economic policy measures implemented to mitigate the impact on households and firms. According to a PBO analysis, the household support measures activated by the Government between June 2021 and last September supported average household expenditure by about 3.2 percentage points. The measures also had a significant redistributive effect, as they largely mitigated (88 per cent) the impact of inflation on households with reduced spending capacity (first decile of the distribution of equivalent spending).

The mismatch between labour supply and demand continues to grow

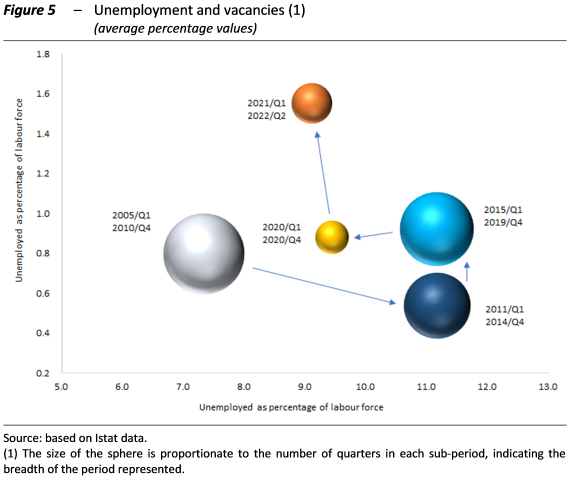

In July-August, employment growth halted, mainly due to the contraction in female employment (-0.2 per cent compared with the second quarter). According to preliminary monthly data, the unemployment rate continued to decline in the summer (to 7.8 per cent on average in the July-August period), but this was attributable solely to a decline in job seekers. Moreover, as the activity rate falls, the gap between labour supply and demand widens further (Figure 5).

Developments in the vacancy rate in the second quarter varied across sectors, holding steady in manufacturing and construction, but still rising sharply in services.

The impact of a permanent shock to energy prices

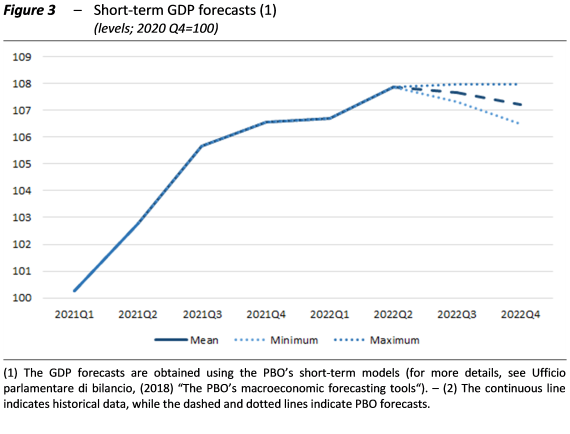

The PBO has recently modified the MeMo-It macroeconometric model, which is also used for the endorsement of the MEF forecasts, to quantify the macroeconomic impact of changes in the price of gas on the Italian economy. A permanent shock of 10 per cent in the price of gas has a stagflationary impact that is no less than that attributed to oil prices and is potentially even stronger. With regard to real growth, the increase in the price of gas trims GDP growth starting from the second year of the shock (-0.1 points), with the negative impact progressively increasing to a peak in the fifth year ( -0.25 percentage points). The decline in investment also has an impact, which is less pronounced than that in GDP in the initial years of the shock but converges toward that in GDP in the fifth year (around -0.3 percentage points) and becomes more accentuated thereafter. At the same time, higher inflation depresses real disposable income. Private consumption falls more than GDP in the first year and almost as much as GDP in subsequent periods (about -0.2 points in the sixth year; Figure 6).

It is estimated that the rise in gas prices (which tripled this year compared with their level in 2021) has subtracted about one percentage point from GDP growth in 2022. If gas prices were to remain at these levels over the next two years, the overall impact on the level of GDP in 2024 (three years after the shock) would be around three percentage points.