20 June 2023 | The Budgetary Policy Report of the Parliamentary Budget Office (PBO) examines recent trends and future prospects for the Italian economy and public finance; it also contains thematic in-depth analyses of the new European governance framework, the anti-poverty measures reform and the distributional impact of inflation on households.

Italy reacts to economic shocks and achieves higher growth than its main European partners in 2022

The year 2022, despite starting with a gradual return to normal after the pandemic, was marked by exceptional and unexpected global events, starting with Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

As a result there was a deterioration in confidence indicators and growth and inflation prospects, particularly for the economies that heavily relied on Russia’s energy supplies. In the months following the beginning of the war, uncertainty regarding the the outlook of the world economy increased and in several developed countries the rise of the inflation reached peaks that were only seen before in the 1980s, prompting central banks to start monetary restrictive policies to keep expectations contained.

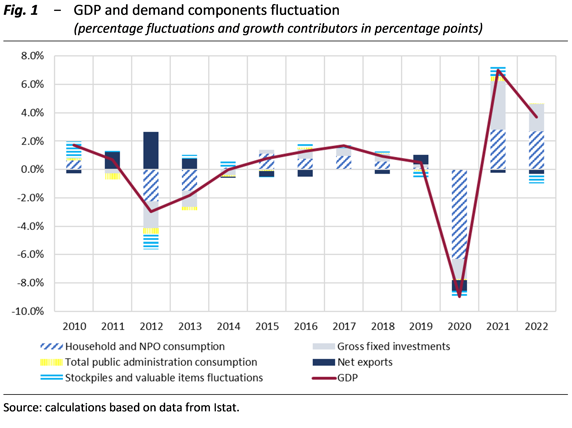

Faced with this factors, the Italian economy showed signs of resilience to adverse economic shocks: in 2022 it achieved a growth rate of 3.7 per cent, surpassing its main European partners. The growth was widely driven by demand, namely household consumption, gross fixed investments and exports (fig. 1).

While expectations for 2023 improve, downturn risks remain in the medium term

At the start of 2023, the general framework based on available indicators was favourable, despite the persistence of headwinds such as the war in Ukraine, high inflation and new financial concerns. Italy’s GDP growth in the first quarter of this year (0.6 per cent in quarter on quarter rates) surpassed the expectations of the Italian Ministry of Economy and Finance (MEF) and the PBO panel. Currently, this year’s predictions have upside risks; however, in the medium term (especially for 2024), risk factors for our country are on the downside, as well as expectations of the global economic scenario.

The National Recovery and Resilience Plan (NRRP) implementation and timeframes are key elements to consider when assessing macroeconomic and public finance forecasts. According to an updated PBO estimate, the NRRP will impact the national GDP by nearly three percentage points by 2026. A plan reformulation is underway to facilitate the feasibility of the projects included. Therefore, the consequences on budget balances and the economy must be carefully assessed.

All the opportunities available through the NRRP review must be fully seized to ensure new momentum for reforms and infrastructure development, both of which are essential to overcome generational, gender and territorial divides, and allow the Italian economy to tackle the future technological and environmental challenges ahead.

Macroeconomic forecasts: an ex-post evaluation

The Report addresses the issue of the accuracy of macroeconomic forecasts, a key aspect for the assessment of the budgetary policies.

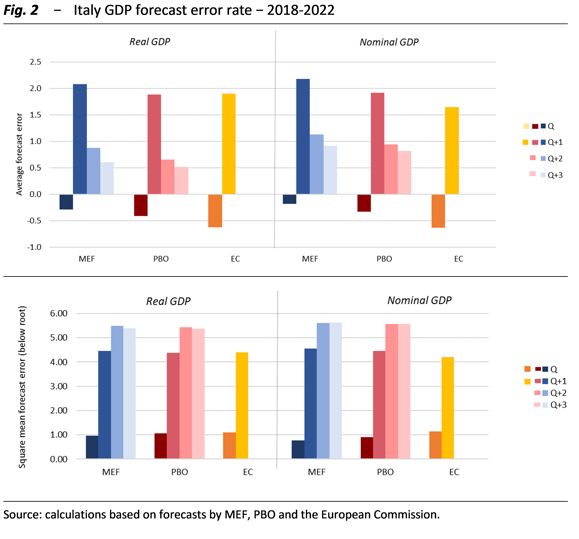

The analysis reveals that over the years 2018-2022 forecasts by the MEF, the PBO and the European Commission on real GDP are slightly pessimistic for the current year, while they appear more optimistic on a longer timeframe, especially for one year ahead, with the MEF being the more optimistic; a positive bias has also been recorded for the nominal GDP in t+1, which in turn decreases on a longer timescale; the orders of magnitude in errors are similar across institutions and are increasing with the time horizon, as expected by the theory (fig. 2).

Forecasts accuracy is crucial to avoid the creation of unrealistic fiscal space, which could undermine the effectiveness and credibility of budgetary planning.

The analysis of the government’s forecasts reveals that after 2014, the year in which the PBO was established and started the endorsment of the macroeconomic forecasts of the government (DEF and NADEF documents), GDP estimates − especially real GDP − have become more balanced. Additionally, looking at the order of magnitude in errors, accuracy in government forecasts has also improved since 2014.

Public finance: from emergency to normalisation

From a public finance standpoint, 2022 can still be seen as a year of emergency. The central government deficit amounted to 8 per cent of GDP, down from the 9 per cent of the previous year, but still high for the third year in a row. This result was mainly driven by various measures put in place to cope with the effects of the energy crisis and the new accounting rules of some construction-renovation bonuses (the Superbonus and the Façade Bonus). Another significant impact factor is represented by higher interest expenditure, over EUR 83 billion, almost EUR 20 billion higher than in 2021. After eight years of consecutive reductions, also in nominal terms, debt service charges rose again by more than 10 per cent in 2021 and by more than 30 per cent in 2022. After the Superbonus and Façade Bonus accounting reclassification, the deficit would have amounted to 5.7 per cent of GDP, generally in line with the policy targets.

The public debt/GDP ratio decreased to 144.4 per cent at the end of 2022, down 5.5 percentage points from 149.9 per cent reached the year earlier.

After the emergency period, the year 2023 can be considered a transitional year. The DEF’s deficit (which also takes into account the effects of the recently approved Decree-Law 48/2023) is expected to fall significantly, to 4.5 per cent of GDP, also benefiting from the considerable downscaling of the effects of the Superbonus and Façade Bonus, along with a substantial decrease in measures combating high energy prices.

Looking ahead, the three-year period from 2024 to 2026 should be marked by a gradual return to fiscal policy “normalisation”, after the exceptional suspension of the numerical constraints from the Stability and Growth Pact.

The DEF 2023 public finance policy scenario confirms the previous path of deficit and debt reduction in relation to GDP. The target of a deficit at 3 per cent of GDP in 2025 (3.7 per cent in 2024) has been confirmed, and a further reduction to 2.5 per cent is planned for 2026. Also reconfirmed is the strategy of gradually reducing the public debt/GDP ratio: after a reduction in 2022, the public debt/GDP ratio is expected to decrease further in the following years, to 142.1 per cent in 2023 and 140.4 per cent in 2026.

The goal of reducing the public debt/GDP ratio with a gradual budgetary adjustment roadmap that avoids an excessively unfavourable impact on growth, and within a context of more stable budgetary planning over time, appears to be in line with the spirit of the proposals for reforming the EU’s fiscal rule framework. However, in 2024, the year in which the clause that suspended the current rules of the Stability and Growth Pact will be removed, the deficit is still projected to exceed 3 per cent of GDP; the outlook on the reduction in the public debt/GDP ratio foresees a contraction by an average of about 0.6 percentage points in the three-year period from 2024 to 2026, lower than previously projected.

The stability of the draft budget balances presented in the DEF 2023 seems realistic; the achievement of these goals should be facilitated, at least in the short term, by the gradual phasing out of the measures aimed at containing the pandemic and energy crises.

It is worth pointing out a number of elements of uncertainty concerning the public finance outlook, linked both to the macroeconomic scenario, the implementation of the NRRP and certain aspects of budgetary planning. As concerns the latter, uncertainties surrounding the identification of adequate financial coverage of devised budget measures need to be resolved: 1) the “unchanged-policies” measures (in particular, the renewal of public sector employment contracts); 2) any financial needs arising from the legislative measures linked to the draft budget law listed in the DEF (including the one on the legal framework on pension); 3) possible financial needs related to the reduction of the tax burden during the legislatureas well as to the new measures that the Government will decide to adopt as part of the end-of-year draft budget law as announced in the DEF.

Concerning the possibility of a reduction in the tax burden, the DEF refers, among possible financial compensating measures, to more extensive collaboration between tax authorities and taxpayers. Interventions aimed at increasing tax compliance are important for fighting tax evasion, but their financial effects are uncertain and of an ex ante nature. For the sake of caution, it would therefore be desirable not to use them to cover structural interventions.

Overall, it would therefore seem that substantial financial covering resources are required, which appear difficult to collect after the period of consolidation in the recent past and without affecting the provision of services and the implementation of social policies, as it is also made clear by the relatively limited savings that the Government plans to secure from tighter spending review of Ministries in the coming years.

IN-DEPTH ANALYSES

The new EU governance and its impact on public finance

The legislative proposals for reforming the EU’s budgetary rules framework, presented by the European Commission last April, include important innovations for both the preventive and corrective parts of the Stability and Growth Pact, as well as for national budgetary procedures.

The proposal contains a number of positive elements, although bigger ambition towards the establishment of a shared budgetary capacity seems necessary. Compared to the existing numerical rules, the new framework seems better suited to balancing the equally important objectives of sustainability in public finances, stability of the economic cycle and GDP growth.

An important innovation comes from the strengthening of ownership by Member States, defined as the increase in their participation and accountability in defining their own budgetary adjustment roadmap. Member States with deficits above 3 per cent or a debt level above 60 per cent of GDP will have to submit Structural Budget Plans with multi-annual consolidation programmes to ensure, in the medium term, the continuous reduction of the debt stock in relation to GDP and a level of deficit below the threshold of 3 per cent of GDP. The plans will cover a minimum duration of four years, extendable to seven if the country commits to structural reforms and investments aimed at sustaining potential growth and improving the sustainability of public finances. A greater direct involvement by Member States enhances the credibility of each country’s fiscal consolidation path with potential positive effects on financial markets and interest rates. In this respect, Member States should be able to consult with the Commission in advance on the rationales of the technical trajectories made public at the start of the procedure.

The decision to focus, in the annual monitoring phase, on a single indicator, the net primary expenditure financed from national resources, appears to have positive impllications. On the one hand, this decision makes sure that fiscal policy is not based on multiple indicators that often provide unambiguous signals. On the other hand, net primary expenditure financed from national resources includes items that are under national governments’ control and does not affect the extent and composition of Member States’ budgets. For monitoring purposes in particular, primary expenditure will be calculated after the impact of discretionary revenue measures. Governments will therefore be able to decide on overall expenditure increases as long as these are financed by corresponding discretionary revenue-increasing measures.

The focus on the sustainability of public finances in the medium term provides an incentive to strengthen the quality of fiscal policy at the national level, as it preserves components, such as public investment, that have a greater impact on growth.

A critical aspect of the new regulatory framework concerns the foreseen margins of flexibility in case that the initial predictions turn out to be unrealistic over time. The clause relating to exceptional events per individual country, currently envisaged only for natural disasters, should also be extended to trends in macroeconomic variables that turn out significantly worse than those originally assumed.

Moreover, the new framework does not include adequate incentives to ensure an appropriate orientation of fiscal policy at the euro area level. In the absence of adequate safeguards for the coordination of national fiscal policies, and between these and the shared monetary policy, fiscal rules risk leading to overly restrictive fiscal stances for the euro area, at least in the coming years during which most countries will have to implement adjustment plans.

Finally, the establishment of a common budgetary capacity, which would allow for a more effective economic governance of the euro area, is not included in the Commission’s reform proposal. Its addition would allow financing investments linked to a strengthening of European public goods (e.g., green and energy transition) and to conduct policies aimed at stabilising the economic cycle for the euro area as a whole. It is therefore advisable that important steps are taken in this direction, once the new EU budgetary rules framework is approved.

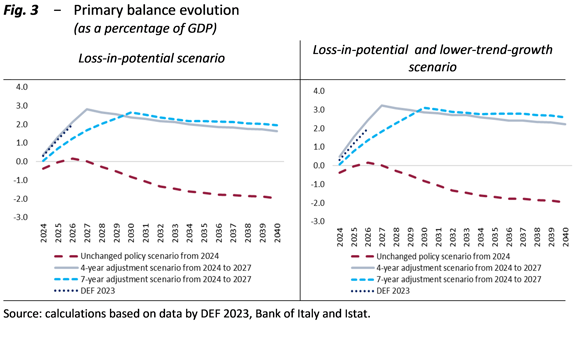

The PBO’s medium-term projections show that, in order to comply with the new rules framework and allow for a plausible decline in the debt/GDP ratio in the medium term with a net borrowing below 3 per cent of GDP, the Italian primary balance should reach a surplus of around 2.8 to 3.2 per cent of GDP by 2027, following a budgetary adjustment over four years depending on scenarios of more or less favourable growth in potential output. Similar values of the primary balance would have to be achieved by 2030 if budgetary consolidation were more gradual, over a period of seven years (fig. 3).

The DEF goals leading to 2026 appear consistent with such adjustment paths. It is therefore crucial that the latter are confirmed in future policy documents and that the consolidation path continues after 2026, until adequate primary balance surpluses are achieved. This would allow the public debt/GDP ratio to decrease at a steady and plausible rate, both in the short term and in the medium term, even in the face of adverse macro-financial shocks and the increase in foreseen expenditures due to an aging population.

From Citizenship Income to Inclusion Allowance: the reform of poverty measures

The expenditure incurred from April 2019 to April 2023 for the Citizenship Income (RdC) and the Citizenship Pension (PdC) amounted to EUR 30.3 billion (with a peak of EUR 8.8 billion in 2021). The number of beneficiary households (initially amounting to 570,000) grew steadily, except for the initial months and October 2020 (due to compulsory suspension after eighteen months of benefit), until it reached 1.4 million in July 2021; in the following months, a gradual decrease began, which continued in the first months of 2023.

The attempt to combine the guarantee of a minimum income with labour market participation of the recipients was tackled through conditions and obligations that required a complex and perfectly attuned administrative operation. The outcomes were conditioned by the slow and difficult start of organisational procedures, also due to the simultaneous pandemic crisis. However, Anpal data show that more than 30 per cent of the total number of beneficiaries managed by job centres has entered an employment agreement over the course of the programme. As labour market conditions improved, this contributed to a reduction in the number of RdC beneficiaries, which have decreased by more than 25 per cent since the end of the pandemic.

The decree law 48/2023 completes the redesign of measures aimed at contrasting poverty initiated by the government with the 2023 Budget Law, by introducing a new provision, the Inclusion Allowance (AdI), to replace the RdC.

Individuals aged 18 to 59 who are not disabled and not involved in care work are excluded from the measure, unless they are living with an individual who is unable to work. To this community is directed the introduction of the Training and Employment Support (SFL), a financial allowance covering a maximum duration of 12 months, on condition of participation in training, guidance and work shadowing projects.

The design of the new allowance seems to be oriented towards a decisive countering of the disincentives to labour market participation, typically associated with universal anti-poverty measures, seeking to limit the target group of beneficiaries to those who face obstacles to entering the labour market due to easily ascertainable objective conditions.

While the calculation criteria of the new allowance generally follow those of the RdC, they also include a redefinition of the amounts, which are generally higher than the current ones for households with disabled people and for those with children under three years of age. The possibility for AdI recipients to benefit from the Universal Child Allowance (Assegno unico) in full and not in a reduced form, as is the case for RdC recipients, entails a greater benefit for households with underage children, which could however suffer an overall reduction in treatment due to the failure to take into account, in the calculation of the AdI, other adults present in the household who are not carrying care work. The reduction of the income threshold for rent households may also result in households with relatively higher incomes losing the benefit.

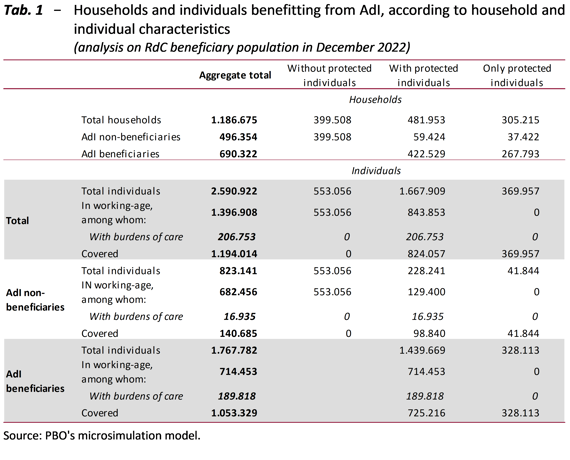

According to estimates conducted with the PBO’s microsimulation model, fed with a longitudinal sample of administrative data related to ISEE declarations and actual issuing of the RdC in the three-year period 2020-22, of the almost 1.2 million households benefiting from the RdC, about 400,000 of them (33.6 per cent) would be excluded from the AdI programme, as they are not made up by protected category individuals. Of the approximately 790,000 households remaining, which include protected category individuals, about 97,000 (a little more than 12 per cent) would be excluded from the AdI programme due to economic constraints. Overall, the number of households benefitting from the AdI programme would therefore be estimated at about 740,000, of which 690,000 already benefiting from the RdC and 50,000 new beneficiaries due to the change in the residence condition (Table 1).

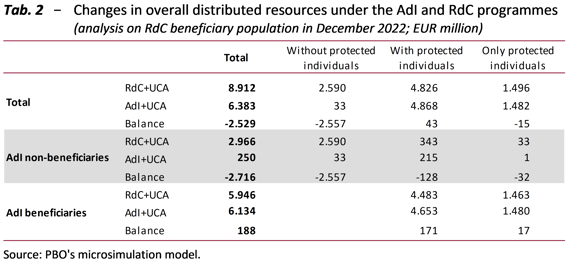

Overall, taking also into account the increased resources deriving from the full compatibility between AdI and the Universal Child Allowance (UCA), households previously benefitting from the RdC programme would receive a total of EUR 6.1 billion, with an increase in benefits of about EUR 190 million, while households previously benefitting from the RdC and excluded from the AdI programme would lose EUR 2.7 billion (Table 2).

The PBO estimates the distribution of households, broken down by the presence of protected category individuals, according to the change in the overall benefit.

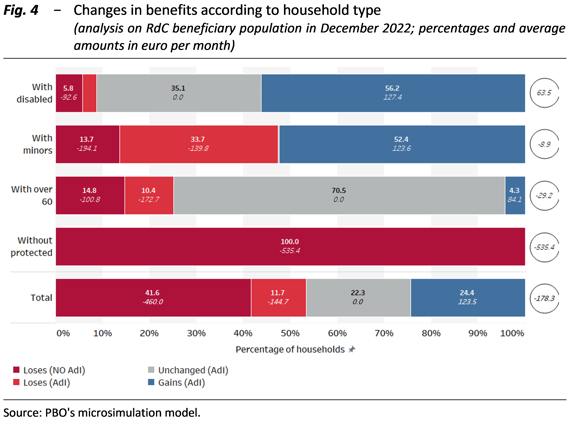

Overall, former RdC beneficiary households that do not access the AdI programme amount to around 42 per cent, with an average monthly loss of about EUR 460. Households without protected individuals, who do not benefit from AdI, lose an average of about EUR 535 per month.

Households with disabled individuals benefit the most from the reform, with an average benefit increase of EUR 64 per month.

Among households with minors (non-disabled), which are those most affected by the change in the calculation of the AdI base amount, slightly more than half will increase the overall benefit (+EUR 124 on average per month) and the remainder will receive lower allowances (33.7 per cent, losing about EUR 140) or none at all (13.7 per cent of households, losing about EUR 194 per month). Considering the total number of households with minors, on average, the benefit is substantially stable (-EUR 9 on average per month).

The households with elderly people over 60 (without disabled people and minors) are the ones whose benefits are least affected by the reform. About 71 per cent of previous recipients of RdC/PdC would be unaffected by the reform. However, also in this type of household there are some who would experience a reduction in their allowance (10.4 per cent, or EUR 173 per month) or a total exclusion from it (14.8 per cent, EUR 101 per month). Considering the total number of households with elderly persons, the benefits would reduce by an average of EUR 29 per month (fig. 4).

No substantial changes are expected in the territorial distribution of AdI compared to that of the RdC, as it predominantly favours households based in the south of Italy (65.8 per cent, compared to 64 per cent for the RdC).

Inflation and its impact on Italian households

The year 2022 was marked by sharp increases in prices, not been observed for roughly forty years: inflation measured by the NIC index reached 8.1 per cent, the highest level since 1985, when it exceeded the threshold of 9 per cent.

The steep surge in prices, started upstream in the production chain as early as spring 2021 as a reflection of commodity price increases, has subsequently spread to consumer items, with a significant impact to the average consumer’s shopping list.

Price dynamics from January 2021 to the end of April 2023 were highly differentiated among categories of goods. A particularly high impact was registered on aggregate housing expenses (+47 per cent) – which includes utilities like gas and electricity (which grew by 196 and 207 per cent, respectively) – and, to a lesser extent, on transport expenses, which were affected by the change in fuel prices (128 per cent). Over the same period, food prices increased by a total of about 20.3 per cent.

A gradual easing of price tensions is expected, with energy components quickly reverting to suitable prices and food and other goods proceeding at a slower pace. Inflationary pressure on household budgets, especially those with lower spending capacity, remains therefore significantly high.

In order to counter the impact of the general increase in consumer prices, and in particular on energy goods, various measures were taken in the second half of 2021 (tariff control measures and monetary transfers), which were maintained and, in some cases, intensified during 2022. In 2023, the extent of support measures underwent a change, with a partial easing of tariff reductions and the removal of the fuel excise rebate, coinciding with the reduction in energy prices.

Overall, according to official assessments, the public funding allocated to mitigate inflationary effects amounted to a total of EUR 119 billion, of which EUR 5.6 billion in 2021, EUR 70 billion in 2022, and EUR 35 billion in 2023. Of these, EUR 30 billion were allocated to households, EUR 35 billion to businesses, and an additional EUR 35 billion to both.

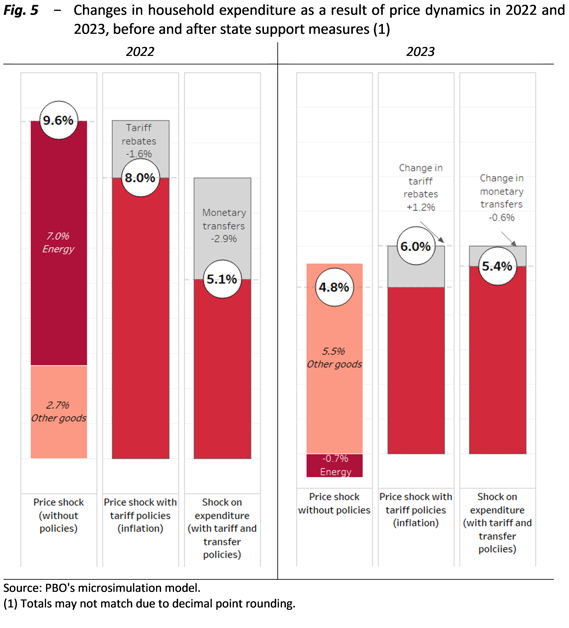

Using the microsimulation model fed with data from the Istat household expenditure survey (HBS) integrated with administrative tax, contribution and welfare information (pensions and ISEE) and incorporating internal inflation estimates, the PBO estimated the annual change in household expenses for 2022 and 2023 due to price dynamics and mitigation policies on a representative sample of Italian households.

For 2022, the impact on household expenses related to price increases has amounted to around 9.6 per cent (of which about 7 percentage points are due to price increases in energy costs and 2.7 to inflation in other goods), but mitigation policies helped to alleviate it by about 4.5 points, bringing it down to 5.1 per cent (fig. 5). In detail, tariff discount policies contributed to the reduction of household expenditure by 1.6 percentage points, whereas monetary transfers by 2.9.

Considering the same consumption basket composition, the gross impact of price growth in 2023 amounted to 4.8 per cent, as a consequence of the increase of non-energy goods prices (+5.5 per cent) and the fall of energy costs (-0.7 per cent). However, the gradual reconsideration of support policies (lower tariff discounts only partly offset by higher monetary transfers) led to a further increase in expenditure of 0.6 percentage points: the final net effect is therefore estimated at 5.4 per cent, +0.3 per cent from 2022.

An overall assessment of the impact of inflation and the mitigation measures reveals that, over the two-year period considered, the latter have had the effect of stabilising the impact of inflation: the net increase in household expenses is almost constant over 2022 and 2023 (5.1 and 5.4 per cent).

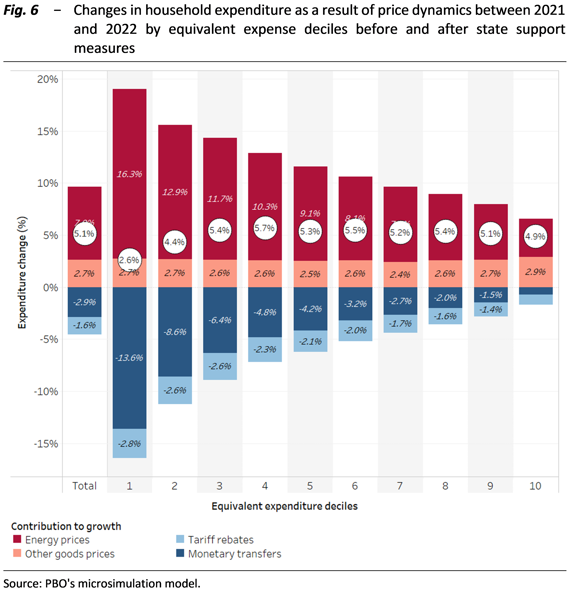

When considering the distributional profile of inflation, it appears that in 2022 the impact on spending of price increases would have been higher for households with lower consumption levels. Interventions implemented by governments more than offset this regressive effect. Therefore, the final net impact in 2022 was progressive, being significantly lower for the first two expense deciles than for the highest deciles (2.6 and 4.4 per cent, respectively, compared to an average of 5.1 per cent; fig. 6).

On the other hand, the increase in the prices of non-energy goods and the rebalancing of the policy mix produce overall weakly regressive effects on expenditure in 2023. The net increase in expenditure in 2023 is higher for the first two expense deciles compared to the last one (6.9 and 6.1 per cent, respectively, versus 5.6 per cent).

As energy inflation eases and price increases spread to other categories of goods during 2023, the review of mitigation policies will have to take several factors into account. First, the retrenchment of tariff measures may be greater than the reduction in energy prices, contributing to overall inflation. Secondly, inflation may be more persistent, which could entail a reapplication of some of the measures in the second part of 2023 to mitigate the effects of non-energy related inflation.

In the latter case, it is advisable that new measures be more decisively focused on the households most in need, in order to accentuate redistribution; furthermore, they should be designed to provide the necessary incentives to achieve more ambitious energy saving targets also by means of market price signals, and be accompanied by adequate financial coverage so that the state of public finances would not be put at risk.