21 October 2025 | This Focus analyses the immediate consequences of the agreement reached by the G7 in June, which excluded multinational groups based in the United States from the Global Minimum Tax (GMT) rules on the profits of large multinational enterprises (MNEs). It also highlights the outstanding issues and the risks inherent in the new scenario.

The GMT was defined in the 2021 Pillar Two agreement, which was signed by the 139 countries participating in the OECD/G20 Inclusive Framework. This marked an important step in the attempt to coordinate international taxation in order to counter profit-shifting and base erosion practices. However, the exclusion of US MNEs represents a radical turning point, which could call into question the compromise that had been reached among the divergent interests of the various participating countries. According to the G7, the decision is based on considering the role of domestic anti-avoidance rules together with the Pillar Two rules, using a so-called side-by-side approach.

After a brief description of the structure of the GMT, this Focus sets out the main characteristics of large multinationals operating in the main OECD countries. It then discusses the content of the G7 agreement, the arguments put forward in its support and the potential advantages that prompted the United States to request the exclusion. Finally, it considers how the GMT might develop in future in light of the agreement.

Under the GMT, the profits of large multinationals – that is, those with revenues of at least 750 million euro – that exceed the ordinary remuneration of the factors of production should be subject to a tax regime ensuring a minimum effective tax rate (ETR) of 15 per cent, regardless of where those profits are located. The objective of the GMT is to counter profit-shifting and base-erosion strategies implemented by MNEs, by providing incentives for tax havens and countries with more favourable corporate tax regimes to raise their effective taxation. This outcome is to be achieved through a system of incentives arising from the interaction of three different components of the taxation of global MNE profits, which provide for a top-up tax whenever the ETR calculated on profits according to the GMT rules falls below the minimum rate of 15 per cent.

The first component of the GMT, the Qualified Domestic Minimum Top-up Tax (QDMTT), may be applied by individual countries in which subsidiaries of resident and non-resident MNEs operate (source countries). The second component, the Income Inclusion Rule (IIR), may be introduced in the countries where the MNEs are resident and provides for the inclusion of the non-repatriated foreign profits of MNEs in the taxable income of the ultimate parent companies (UPEs) for the purposes of computing the minimum effective tax rate. This component applies only where source countries have not adopted a QDMTT. The third component, the Under-Taxed Profits Rule (UTPR), may be activated by countries where an MNE resident in another country that has not adopted the IIR operates through a subsidiary or associated entity. In particular, these countries may tax both the profits generated by the MNE in other jurisdictions that have not introduced a QDMTT and those produced in the country where the ultimate parent is located if the IIR has not been applied there. The QDMTT is the cornerstone of the system. Low-tax countries hosting MNE subsidiaries, including tax havens, are in fact strongly incentivised to adopt it in order to avoid surrendering tax revenue to residence countries through the IIR or seeing the UTPR applied in their territory by third countries.

From the outset, the debate on the GMT rules has highlighted a number of issues relating to the limits and weaknesses of the new tax system. Firstly, implementation of the rules has immediately revealed a high degree of administrative complexity. Secondly, the GMT rules increase the tax burden on MNEs and constrain the use of tax incentive policies by national governments. This aspect has attracted criticism, particularly from developing countries, but it is also relevant in the European context. Thirdly, the UTPR has been criticised for its extraterritoriality, as it would allow a country other than the MNE’s home country or those in which its subsidiaries or affiliates are based to levy an additional charge.

The effectiveness of the GMT rules is heavily influenced by the number of participating countries and by their importance in terms of the number and the profits of resident large MNEs. The 2021 GMT agreement was signed by 139 countries, most of which (67) have implemented the new rules, or plan to do so by 2026, either in full or at least partially. In December 2022, the European Union adopted a directive requiring the 27 Member States to introduce a global taxation model that broadly follows the rules developed at the OECD (EU Directive 2523/2022). That directive has been progressively transposed by almost all Member States, including countries such as Ireland, Luxembourg and the Netherlands, which had previously opposed initiatives to strengthen tax coordination. In Italy, the directive was transposed by Legislative Decree No. 209/2023 and has been in force since 2024. Key G20 countries, however – notably the United States, China and India – which initially supported the OECD proposal, did not subsequently transpose the GMT rules.

The most critical issue concerns the stance taken by the United States. Even under the Biden administration, the United States suspended the adoption of the GMT rules after signing the agreement. The US administration believes that the introduction of these rules by other countries would, through the UTPR, amount to an extraterritorial levy. This would have negative effects on US tax revenues and be detrimental to US fiscal sovereignty, or at least discriminatory against US companies. Following the inauguration of the Trump administration, the United States not only definitively withdrew from the implementation of the rules but also conducted a campaign against countries that had adopted them. This culminated in a G7 agreement in June this year, which provided for the exclusion of US-based MNEs from the application of the IIR and the UTPR.

The core issue in the G7 agreement is the need to take account of the role of domestic anti-avoidance rules – in the United States, the Global Intangible Low-Taxed Income (GILTI), the Base Erosion and Anti-Abuse Tax (BEAT) and the Corporate Alternative Minimum Tax (CAMT) – alongside the Pillar Two rules, under a so-called side-by-side approach. This would make it possible to exclude US MNEs from the application of the GMT rules. The argument nonetheless raises a number of concerns. While the US anti-avoidance provisions display some similarities with the GMT, they differ in several important respects in their implementation and, above all, are designed solely to safeguard national tax revenues and the competitiveness of US MNEs. In this context, it is not straightforward to determine the extent to which these objectives can be reconciled with those of the GMT.

An analysis of the profits of US MNEs generated in the United States and abroad, as well as of the profits produced in the United States by non-US MNEs, helps to illustrate both the incentives for the United States not to adopt the GMT rules and the advantages of the G7 agreement in terms of revenue, tax policy autonomy and the competitiveness of US MNEs. Overall, there is considerable uncertainty surrounding the revenue effects. However, any potential revenue losses could be offset by the clear benefits for the autonomy of national tax policies and for the competitiveness of domestic MNEs made possible by the agreement. These considerations can therefore help to explain why the US administration is determined to secure the exclusion of US MNEs from the GMT rules (IIR and UTPR).

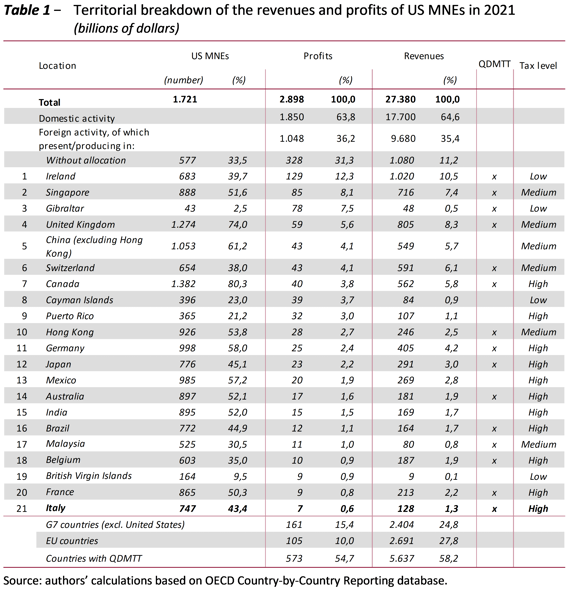

In terms of the quantitative significance of the G7 agreement, OECD Country-by-Country Reporting data show that large MNEs based in the United States accounted for a very substantial proportion – 22.6 per cent – of all MNEs worldwide in 2021. These companies generated almost 32 per cent of global profits (and 26.4 per cent of global revenues). Of these profits, 63.8 per cent were earned in the United States, with the remaining 36.2 per cent earned by foreign subsidiaries or affiliates. Focusing on the profits of MNEs earned abroad, 31.3 per cent were realised in countries that are not identified in the Country-by-Country Reports (the “Without allocation” row), while 54.7 per cent were earned in countries that have applied the QDMTT and are expected to continue to do so after the agreement. Finally, 14 per cent of profits were generated in countries that had not applied the QDMTT before the agreement and where the UTPR could therefore have been activated. The agreement now excludes this possibility (see Table 1).

The agreement reached within the G7, whose operational aspects still remain to be defined, raises a number of critical issues, especially in the light of the significance, outlined above, of the US MNEs excluded from the GMT rules. Firstly, as the agreement was reached within the G7, it is unclear how it will be received by the other G20/Inclusive Framework countries that have signed up to Pillar Two. Furthermore, the European Union, which has transposed the GMT almost in full through its own directive, will likely need to amend the EU legal framework in this area. Secondly, other countries may demand equivalent treatment to that granted to the United States under the G7 agreement, which would have implications for international tax coordination. Finally, it is far from certain that the truce afforded by the G7 agreement will prove lasting. The US administration could build on the results obtained in a short time by opening new negotiation fronts, for example on the unresolved issue of digital services taxes, which many countries, including Italy, have introduced unilaterally due to the allegedly discriminatory nature of these taxes with regard to US big tech companies.