11 April 2024 | In the broader context of tax expenditures rationalisation, the Focus Paper analyses the impact of recent interventions to curb deductions for expenses and donations for personal income tax (Irpef) purposes, outlining recent developments and analysing beneficiaries. More specifically, reference is made to the provisions of the 2020 Budget Law (Law No. 160/2019) and the first part of the personal income tax reform (Legislative Decree No. 216/2023).

Italy has long been trying to launch measures to curb tax expenditures, namely, that broad set of reductions, exemptions and special taxation schemes that contribute to making the tax system less fair and transparent and more distorting, resulting in a significant loss of revenue. Since 2009, annual analyses have been ordered to gather useful data for reform purposes. As of 2016, the monitoring process is performed by a dedicated Committee and constitutes groundwork for a policy document to be attached to the Update to the Economic and Financial Document (NADEF), which is expected to outline the reduction or reform measures to be adopted in the following budget law. Despite these actions, recourse to tax expenditures has increased further in recent years: between 2018 and 2024, the number grew by a third, from 466 to 625, and the overall revenue loss doubled, from 54 to 105 billion. In particular, special schemes and exemptions increased and the rise in tax credits (especially those related to construction work) was exceptional; this was accompanied by a greater recourse to specific forms of exemption such as corporate welfare. In all the years considered, Irpef is the tax with the highest prevalence of tax expenditures: 200 items (about 32 per cent of the total) in 2024, plus another 59 items whose effects are also felt on other taxes. Together with inheritance and gift taxes and tax credits, Irpef is the tax registering the largest increase in tax expenditures (+65 per cent from 2018 to 2024).

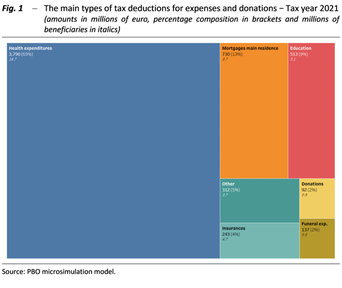

The tax expenditures covered by recent interventions, those referring in general to Irpef deductions for expenses and donations, account for a very small part of the overall tax expenditures (about 6 per cent according to the estimates of the latest Annual Report on Tax Expenditures). More than half of taxpayers (54 per cent, or 22.6 million individuals) reported in 2021 expenses and donations corresponding to approximately 6.3 billion tax deductions. Almost all of these (more than 98 per cent) consisted of tax deductions for expenses, while tax deductions for health care expenses accounted for about two-thirds of the total (65 per cent) and were used by 18.7 million taxpayers (Figure 1). This was followed by tax deductions for interest on mortgages for the purchase of a main residence (730 million out of 3.7 million beneficiaries), for education expenses (513 million out of 3.1 million beneficiaries), for insurance (243 million out of 4.7 million beneficiaries), and for funeral expenses (137 million out of 0.5 million beneficiaries). Approximately 312 million were then distributed over a wide and varied set of about 25 types of minor tax expenditures.

The analyses show that the amounts of tax deductions actually enjoyed by taxpayers are in general relatively low. In 2021, half of the recipients enjoyed tax deductions below EUR 175, while only 4 per cent benefited from a tax rebate higher than EUR 1,000. Overall, tax deductions are mainly claimed by higher-income taxpayers: the poorest 50 per cent of taxpayers enjoy about 15 per cent of the total tax deductions, while the richest 10 per cent benefit from 26 per cent. As income rises, the share of those benefiting from tax deductions and the average amount deducted increases, while the incidence of the benefit with respect to the gross tax decreases. This last impact is particularly high for the relatively few taxpayers with lower incomes who have sufficient gross tax liabilities to benefit from tax deductions. The distribution of the different micro-tax benefits based on income is, however, markedly heterogeneous.

The analyses show that the amounts of tax deductions actually enjoyed by taxpayers are in general relatively low. In 2021, half of the recipients enjoyed tax deductions below EUR 175, while only 4 per cent benefited from a tax rebate higher than EUR 1,000. Overall, tax deductions are mainly claimed by higher-income taxpayers: the poorest 50 per cent of taxpayers enjoy about 15 per cent of the total tax deductions, while the richest 10 per cent benefit from 26 per cent. As income rises, the share of those benefiting from tax deductions and the average amount deducted increases, while the incidence of the benefit with respect to the gross tax decreases. This last impact is particularly high for the relatively few taxpayers with lower incomes who have sufficient gross tax liabilities to benefit from tax deductions. The distribution of the different micro-tax benefits based on income is, however, markedly heterogeneous.

Besides the legislative interventions that directly affect the size of tax deductions, there are also the natural dynamics of existing ones, which follow the economic, social and institutional phenomena to which they are structurally linked. Since 2010, tax deductions for expenses and donations have increased by about one billion (6 per cent higher than inflation), mainly due to the growth in tax deductions for healthcare expenses (+1.4 billion, +40 per cent in real terms), due to the evolution of healthcare expenditure, but also to the increasing use of the pre-filled tax return, which automatically records these and other deductible expenses. Donations to third sector organisations increased significantly, albeit on a smaller scale in terms of overall volume (+54 million, +124 per cent in real terms), due both to the increase in the average amount of donations and in the percentage of deductibility as a result of the various measures enacted during the period under review.

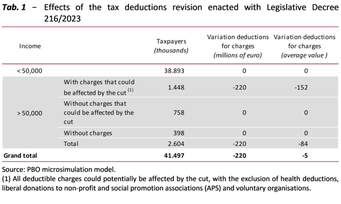

The decree implementing the first part of the Irpef reform provided for by the enabling law (Law No. 111/2023) established, in addition to a change in rates and tax brackets, a cut in tax deductions for expenses and donations through the introduction of a non-deductible threshold of 260 euro for taxpayers with a total income above EUR 50,000. This would render the advantages of the tax rate reduction ineffective for the recipients affected by the cut.

The reform involved about 1.4 million taxpayers, slightly more than half of the taxpayers with incomes over EUR 50,000, and about 6 per cent of taxpayers with tax deductions for expenses (Table 1). The average cut applied to the taxpayers affected (equal to EUR 152) is lower than the non-deductible threshold, and this derives from the fact that only a portion of taxpayers have tax deductions exceeding EUR 260 (about 36 per cent) that can be affected by the cut.

The Focus Paper also analyses the effect of the amendment that was made to the draft legislative decree following the debate in the parliamentary committees, which excluded from the cut the various forms of donations in favour of non-profit organisations, humanitarian, religious or secular initiatives and third sector organisations. Overall, the change benefited the approximately 157,000 taxpayers with incomes above EUR 50,000 who make donations (out of a total of approximately 900,000). However, the cut would not have affected the approximately 500,000 taxpayers who make liberal donations by opting for the deduction scheme.

The Focus Paper also analyses the effect of the amendment that was made to the draft legislative decree following the debate in the parliamentary committees, which excluded from the cut the various forms of donations in favour of non-profit organisations, humanitarian, religious or secular initiatives and third sector organisations. Overall, the change benefited the approximately 157,000 taxpayers with incomes above EUR 50,000 who make donations (out of a total of approximately 900,000). However, the cut would not have affected the approximately 500,000 taxpayers who make liberal donations by opting for the deduction scheme.

The tax deduction containment envisaged by the first module of the Irpef reform follows a measure with the same purpose introduced with the 2020 Budget Law. However, it presents different application modalities that have overlapped in a non-transparent combination – as shown in the microsimulation analysis reported in the Focus – which risks generating further complications for the taxpayer.

Compared to the original rationalisation objectives, having focused exclusively on tax deductions for expenses and donations by establishing limits and thresholds does not seem to have led to tangible progress in reducing tax expenditures. The tax delegation itself, while calling for a reorganisation of the tax expenditures, continues to safeguard the most conspicuous components. Therefore, fragmentation and lack of transparency in the system, the tendency to favour mainly high-income taxpayers, and the difficulties of low-income taxpayers in obtaining benefits due to their low gross tax liabilities – a phenomenon that is also growing as a result of the progressive increase in the Irpef exemption thresholds and the increased use of other forms of tax deductions, such as those related to building renovation expenses – continue to persist in the system.

Among the viable alternatives for the reorganisation of tax expenditures discussed in the literature is the revision of reliefs in coordination with expenditure and revenue policies, including cost-sharing. With regard to healthcare, for example, tax reliefs could be reconsidered in the context of a broader reflection on the level of funding of the National Health Service, on the role of health insurance (already the subject of tax relief in the context of corporate welfare) and on cost-sharing mechanisms such as co-payments for medical fees, which alone account for potential tax reliefs of around 500 million.

For the other minor benefits, the transformation of tax deductions into spending programmes (ad hoc bonuses) of defined duration and renewable through subsequent legislative interventions could be, if circumstances justify it, a further viable alternative, regulated in an efficient way by various telematic platforms that are already widely used. A systematic approach to this transformation could lead to an improvement in the selectivity of incentive benefits towards fairness and efficiency, improved transparency and greater consistency with contingent needs. A monetary transfer may in fact be more effective for those in poorer economic conditions. In this context, moreover, the concept of individual income, proper to the fiscal sphere, could be overcome, favouring instead measures that look at the overall resources and needs of the household.