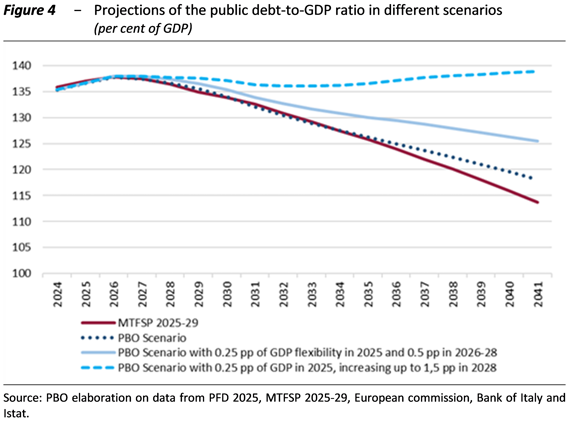

17 April 2025 | The macroeconomic scenario outlined in the Public Finance Document (PFD) 2025 is set in a global context characterised by the escalating trade war and other geopolitical tensions. The introduction of new tariffs by the United States is reducing global growth prospects and has sharply exacerbated market volatility. The protectionist pressures of recent months, although in continuity with the first term of the Trump presidency, is in terms of intensity and magnitude unprecedented in the post-war period (Figure 1). The consequences on the financial, currency and commodity markets reflect an extremely high level of uncertainty, not least because a number of reference points in global economic and financial equilibria seem to be disappearing. The trade war could also push up global inflation; in that case central banks would have to choose between prioritising price stability or avoiding stagflation and accommodating monetary policy as price pressures do not originate from excess demand. International macroeconomic forecasts even before the US administration’s announcements on April 2 pointed to global growth below historical averages, with differences between the main areas: the US expanding, the euro area slowing down, and China’s GDP dynamics lower than pre-pandemic.

The DFP’s international exogenous assumptions were formulated in mid-March and partly anticipated developments on the trade war. The projections of the exogenous variables of the DFP, defined last month, anticipated a tightening of tariffs by the US at starting on April 2; the outcome turned out to be more adverse, also due to the first retaliation by China and to markets reactions. The international exogenous scenario adopted by the Ministry of Economy and Finance (MEF), which appeared reliable few weeks ago, after the most recent developments became unstable and uncertain. On the one hand, protectionism will act as a brake on trade and economic activity; on the other hand, the German stimulus plan for military spending and infrastructure may partly mitigate the unfavourable effects on international trade, especially in Europe. Moreover, wars continue, as negotiations for peace or a truce in the Middle East and Ukraine do not appear fruitful. All in all, the uncertainty perceived by households and businesses is extremely high and financial assets prices are highly volatile. Although some favourable developments cannot be ruled out, the risks of the international scenario are clearly and strongly tilted to the downside.

The Italian economy recorded moderate growth in 2024 (0.7 per cent), below that of the euro area, for the first time since 2021. The change in GDP was supported by domestic demand, in particular consumption, as well as by net foreign demand, amid falling imports. In terms of aggregate supply, the weakness of industry was confirmed, while the services and construction sectors were more resilient. In the final part of 2024 the cyclical phase was almost stagnant, barely better than in the summer period. Household consumption was held back by the loss of purchasing power, capital accumulation recovered, partly due to better credit conditions, but the housing component remained contractionary. Exports recorded their fourth consecutive quarterly decline, but the more pronounced drop in imports favoured an improvement in the balance of payments trade balance. Employment strengthened in 2024, although slowing in the final part of the year, while wages gradually regained purchasing power. After the significant decline in 2024, consumer inflation in Italy showed signs of recovery in the first quarter of 2025, mainly due to higher energy prices.

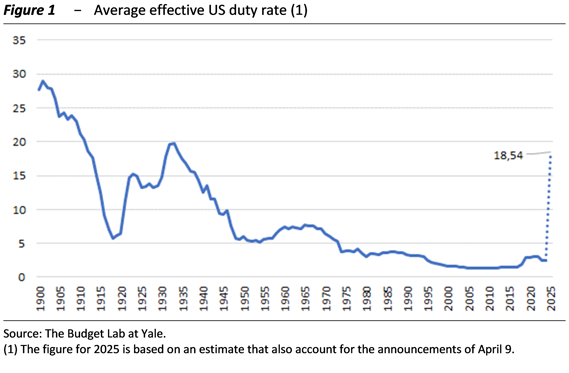

After two quarters of substantial stagnation in the first three months of this year, GDP likely accelerated. Timely monthly quantitative variables point to a slight acceleration of economic activity in the short term, compared to the little more than positive momentum in the second half of 2024. Industrial turnover between the end of last year and the start of 2025 has recovered and, according to the short-term models of the Parliamentary Budget Office (UPB), GDP accelerated last quarter, growing by 0.25 percentage point on a quarterly basis (Figure 2). The risks of the forecast are downward biased and intensify in the medium term, mainly due to geopolitical tensions. Sectoral dynamics are heterogeneous and could differ further, due to the different impact of tariffs on the various production sectors, as Appendix 1.1 shows.

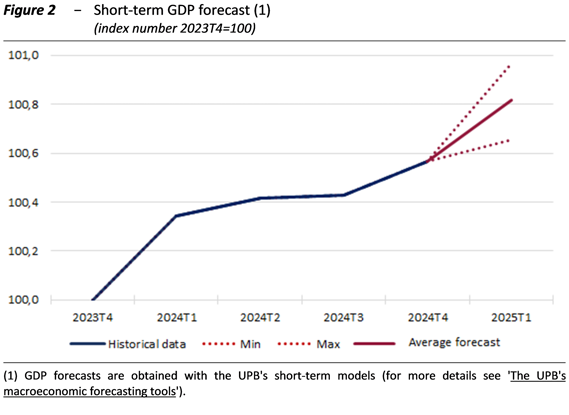

The trend macroeconomic scenario (QMT) of the 2025 PFD projects growth of the Italian economy for this year at 0.6 per cent, just below that of the previous two years (0.7 per cent). In 2026, a slight strengthening of GDP growth is predicted, which is then maintained in the following two years at 0.8 per cent. Over the entire 2025-28 period, GDP would grow by 3.0 per cent. Compared to the policy scenario of the 2025-29 Medium-Term Budgetary Structural Plan (MTFSP), the forecast of the change in GDP was halved for 2025 and revised downward by three-tenths in 2026, mainly due to the deterioration in the international situation. Growth over the forecast horizon would be mainly driven by domestic demand. The downward revisions to nominal GDP are smaller than those recorded for GDP as the change in the deflator is slightly increased. Over the entire forecast horizon the increase in nominal GDP is expected to be slightly below 11.8 per cent, while it was slightly above 12 in the PSB scenario.

UPB’s GDP forecasts, formulated on the basis of the same exogenous variables as those of the MEF, are in line with those of the PFD for the current year, while for subsequent years they are slightly more cautious. Also in the PBO scenario, economic activity would be predominantly driven by domestic demand, which, however, would provide less stimulus than indicated in the PFD; therefore, cumulative GDP growth in the four-year period 2025-28 would be lower, at 2.7 per cent against 3.0 per cent outlined by the MEF.

The MEF’s QMT was validated by the PBO, as the government’s forecasts of the main macroeconomic variables appear to be within an acceptable range (Figure 3). The overall assessment of acceptability of the MEF’s QMT takes into account: a) annual forecasts of real GDP growth that do not exceed the extremes of the UPB panel‘s forecast range and that do not deviate significantly from the median of the panel expectations and the UPB estimates; b) annual projections in the QMT of nominal GDP close to those of the UPB and just above the median of the panel projections; c) between 2025 and 2028 the changes variations of real and nominal GDP in the QMT that are broadly consistent with the range of the panel‘s cumulative estimates, although they are in the upper range.

The risks are tilted to the downside and are mainly due to geopolitical factors, protectionism and conflicts, as well as the management of major investment projects such as the NRRP. As the trade war escalates, the impacts will be differentiated by sectors and between countries, but still adverse overall and with a very uncertain order of magnitude; the final effects will depend on various factors, all of which are uncertain, such as the duration and retaliation of tariffs, the responses of financial markets and central banks, the behaviour of exporting companies and consumers. With regard to domestic aggregate demand for Italy, there are risks on the dynamics of investments and on the realisation of the NRRP projects; given the high concentration of NRRP interventions in 2026, it cannot be excluded that some of the works may be postponed. On the other hand, aggregate demand in Europe could be boosted by new rearmament programmes. As far as financial markets are concerned, stock exchanges will remain very volatile due to global uncertainty, resulting in a highly unpredictable path of central banks’ monetary policies. Last but not least, the global warming trend continues, increasing extreme weather events with negative impacts on prices and the productive fabric.

The effects on forecasts of an update of the foreign demand assumptions and alternative scenarios on rearmament and the NRRP are assessed. An update of the assumptions on foreign demand would result in slightly lower GDP growth for Italy in 2026 and 2027 (by 0.2 and 0.1 percentage points, respectively); the effects are modest as the exogenous factors already partly account for the new duties and the lower foreign demand is largely offset by lower imports. An increase in military spending, gradually using the flexibility clause up to 1.5 of GDP in 2028, could strengthen GDP growth rates by an increasing extent, up to 0.2-0.3 percentage points in the coming years. The deferral of ten billion of NRRP expenditure from 2026 to 2027 would imply a brake on the change in GDP in 2026 by 0.3 percentage points, a marked acceleration (0.8 GDP points) in 2027 and lower growth by 0.4 points in 2028.

A Document for the transition period. – The 2025-29 PFD, pending the transposition of the EU’s new framework of rules into national legislation, takes an intermediate form between what is required by the new European governance and the Economic and Financial Document (EFD) that is mandated by current legislation: it contains more information than the minimum required by the EU but only part of what is usually presented in the EFD. Overall, the information provided is reduced compared to what was presented in the past in the first half of the year.

The PFD updates the trend scenario for the three-year period 2025-27 and provides only some insights for 2028, thus presenting itself as an update document rather than a planning document, useful to set in advance the contents of the budget manoeuvre to be presented in Autumn. Planning indications on the main measures of the manoeuvre are postponed close to the budget law. The EFD, on the contrary, informed Parliament and public opinion, albeit in general terms, of the areas on which the Government intended to possibly intervene with the subsequent public finance manoeuvre and on the sectors from which the possible coverage would come.

Consolidated practice since 1988 envisaged the beginning of the planning cycle in the first half of the year with the EFD – and even earlier the Economic and Financial Planning Document (EFPD) –, with a horizon extended at least to a three-year period. The presentation of the PFD, moreover, could have provided an opportunity to adjust the forecasting and planning horizon to that of the Medium-Term Fiscal Structural Plan (MTFSP). This would have strengthened the medium-term orientation of budget planning, as required by the new European governance.

It would be advisable in the revision of Law 196/2009 to consider maintaining a complete trend framework over the entire horizon, as well as the beginning of the annual budget planning cycle in the first half of the year.

Public finance trend scenario. − In 2024, the deficit turned out lower than in the previous year, mainly due to the lower effects of the Superbonus incentive; it was also lower than expected due to higher-than-expected revenues. The primary balance, i.e. the difference between revenue and expenditure net of interest expenditure, was positive again after four years.

Trend deficits as a ratio to GDP outlined in the PFD for the 2025-27 period confirm the values planned in the MTFSP, at 3.3 per cent in 2025, 2.8 per cent in 2026 and 2.6 per cent in 2027, despite the worsening of GDP dynamics, due to the upward revision of the revenue growth forecast, attributable to carry-over effects from the higher-than-expected outturn in 2024 and the more positive situation in the labour market. The deficit would thus return below the 3 per cent of GDP threshold in 2026, as planned in the MTFSP, thus setting the conditions for an exit from the excessive deficit procedure (EDP) of the Stability and Growth Pact (SGP) the following year.

The primary balance continues to improve over the three-year forecast period, standing at 0.7 per cent of GDP in 2025, 1.2 in 2026 and 1.5 in 2027. Interest expenditure as a ratio of GDP is projected to increase from 2026, when it would stand at 4 per cent from the 3.9 per cent estimated for the current year, before reaching 4.2 per cent in 2027. This pattern reflects the recent upward movement of the interest rate curve, which is generalised for all euro area countries, and high levels of issuance to finance cash requirements, which are still affected especially by the effects of tax credits related to building incentives.

Primary expenditure as a ratio of GDP would increase slightly in 2025 and then fall in the following two years, decreasing overall by 1.2 percentage points (from 46.7 per cent in 2024 to 45.5 per cent in 2027). Current primary expenditure as a share of GDP would decrease the most, but the share of capital expenditure is also expected to fall, mainly due to the decline in capital transfers. The components of capital expenditure show different trends: investment spending would average 3.7 per cent of GDP, up from the already very positive result of last year (3.5 per cent) and well above the final figures of previous years. Capital transfers would average 1.3 per cent of GDP over the three-year forecast period, increasing in 2025 and then decreasing significantly from 2026, due to the ending of the Transition 4.0 business incentives and, from the following year, of the disbursements related to the NRRP. For the latter, the PFD updates the time profile of expenditure; however, the revision does not include the possible effects of the reprogramming currently under discussion with the European authorities, which should be approved by the end of May.

The ratio of revenues to output increases in the two-year period 2025-26 and returns to the 2024 value in the last year; this pattern essentially reflects the time profile of the NRRP grants, which mainly affect other capital revenues and, to a lesser extent, other current revenues. The expected evolution of tax revenues and social contributions in the current year is to a large extent conditioned by the stabilisation of the effects of the relief to the social security burden for employees, which was made permanent by the last Budget Law with changes to the implementation modalities. The tax burden remains stable on average over the three-year period at 42.6 per cent.

The PFD reports only some information on the forecasts for 2028: the path of deficit reduction in relation to GDP would continue, standing at 2.3 per cent, in line with the MTFSP target. A slight increase – not quantified in the document – is projected for interest expenditure and the consolidation of the primary surplus would continue (‘above 2 per cent of GDP’) reflecting the progressive containment of current primary expenditure and the concomitant stability of public investments. According to the PFD, 1.3 billion would be needed in 2026 and 2.4 billion in 2027 to confirm some policies expiring at the end of 2025; however, the document does not specify which measures the government could confirm.

Primary expenditure is an important component of the net expenditure indicator used in the new European economic governance to monitor compliance with budgetary rules; the analysis of its evolution can provide important insights regarding the developments of the overall indicator.

Primary expenditure in 2024 decreased slightly more than projected in the Technical Explanatory Note to the 2025-2027 Budget Law (TEN). In the three-year period 2025-27, the growth estimated in the PFD is, in cumulative terms, higher than that reported in the TEN; in particular, the primary expenditure growth rate estimated in the PFD is above that of the TEN in the two-year period 2025-26 (by 0.2 and 0.6 percentage points, respectively) and in line with that of the TEN in 2027. This is also due to the postponement of NRRP-related expenditures in the two-year period 2025-26. The part of these expenditures financed through EU grants does not impact the net expenditure indicator; therefore, according to the PFD, net expenditure is expected to grow below or in line with the MTFSP (see below).

Some general remarks on the public finance trend scenario. − It is welcome that the current legislation framework confirms the main targets set in the MTFSP and endorsed by the Council of the EU, in particular the return of the deficit below 3 per cent of GDP in 2026 and the growth of net expenditure below the values set in the MTFSP.

However, the public finance framework presents several elements of uncertainty, in relation to increasing volatility and tensions in the international scenario, the effective implementation of the NRRP and to the climate and environmental transitions. New budgetary priorities emerge, in particular the need to strengthen the defence sector in a context of general geopolitical uncertainty. Finally, the projected decline of debt-to-GDP in 2027 depends on particularly favourable assumptions on the stock-flow adjustment component.

Information on the factors underlying the public finance trend forecast is not complete. The elements defining the general government budgetary prospects are discussed only at an aggregate level, without providing relevant details for an in-depth assessment of the projected dynamics. Even less information is provided on the forecasts for 2028. As regards unchanged policies, i.e. the confirmation of some policies expiring at the end of the year, the document does not provide information on measures that could be renewed. The information available to Parliament and the public is thus limited, making it difficult to fully assess the expected developments.

The implementation status of the National Recovery and Resilience Plan (NRRP). – The implementation status demonstrates significant progress, yet delays persist that may compromise the full and timely realization of the NRRP. According to the data available in the ReGiS platform as of 8 April 2025, 95 percent of the financial allocation—equivalent to €184.7 billion—has been activated. However, the actual expenditure amounts to €64.1 billion, representing 33 percent of the total, of which €27.3 billion pertains to the Superbonus scheme and tax credits. In the remaining implementation period, nearly half of the overall milestones and targets must still be achieved. Meanwhile, the expenditure yet to be incurred represents approximately two-thirds of the total allocation. For certain measures, the use of facilities, special-purpose vehicles (SPVs), and dedicated funds enables, on the one hand, the timely achievement of milestones and targets – thereby ensuring the disbursement of instalments by the European institutions – and, on the other hand, the completion of investments and the expenditures beyond 2026.

A total of 291,527 projects are recorded in the ReGiS database. The assessment of their implementation status is hindered by several critical issues in the information base. Specifically, ReGiS includes projects related to the Superbonus scheme but excludes those concerning tax credits under the Transition 4.0 program, which are numerous and currently being uploaded. It also includes ongoing projects originally initiated under measures that were later defunded or excluded from the NRRP following the end-2023 revision (such as nurseries, urban regeneration plans, and the measure ‘towards a safe hospital’), now funded through national legislation.

Although the majority of projects with allocated funding under the NRRP are in advanced stages of implementation – 55 percent, amounting to €100.5 billion, are in the execution phase, and 32.4 percent, or €25.6 billion, are in the completion phase – a significant portion still lacks critical information. Specifically, 3.7 percent of projects, corresponding to €4.9 billion, have no data available. An additional 7.8 percent, equal to €13.5 billion, only list the expected phase based on initial programming, with no indication of the actual start date. Considering the NRRP as a whole, these projects – which may be at the greatest risk of non-completion – correspond to an equal share of grants and loans (12.5 percent). However, notable differences emerge when analyzing individual missions. Mission 2 is the only one where loans (27.4 percent) exceed grants (6.7 percent) among such projects. The opposite holds for all other missions. A particularly pronounced bias toward grants is observed in Mission 3, where 50.5 percent of the financing is through grants compared to just 5.5 percent in loans. For Mission 7, all projects lacking information or with only theoretical phase data are entirely financed through grants.

Finally, in terms of territorial distribution, a higher share of projects in the execution phase is observed in Central and Northern regions, compared to the national average. Conversely, Southern regions show a greater proportion of projects in the final phase of implementation.

Public debt dynamics. – In 2024, the debt-to-GDP ratio increased again, to 135.3 per cent, after reductions in the previous three years, mainly due to the stock-flow component, which includes the cash effects of construction tax credits accrued in past years. However, the debt-to-GDP ratio was 0.5 percentage points lower than projected in the MTFSP, due to both the better-than-expected primary surplus and the carry-over effect on GDP of the upward revision of nominal GDP by Istat.

In 2024, the weighted average cost of new issues decreased to 3.4 per cent (down 0.4 percentage points from 2023). The average residual maturity of general government debt remained high values, at 7.9 years at the end of 2024. Moreover, with reference to the debt-holding sectors, it should be noted that since 2022, the year in which unconventional monetary policies are gradually phased out, the reduction in the share of public debt held by the Bank of Italy has been offset by an increase in the share held by foreign investors and non-financial households and firms.

The current legislation scenario of the PFD shows an increase in the debt-to-GDP ratio to 136.6 per cent in 2025 and 137.6 in 2026, followed by a gradual decline to 137.4 in 2027 and 136.4 in 2028. Compared to the MTFSP estimates, this path is slightly more favourable until 2027 and aligned with the target in 2028. The debt path will continue to be unfavourably affected by the cash effects of the Superbonus incentive (within the stock-flow adjustment), which will remain high especially in 2025-26. Conversely, the realisation of privatisation targets (for a cumulative value of about 0.8 percentage points of GDP in 2025-27) and the reduction of Treasury’s cash holdings should contribute favourably to debt dynamics, and in 2027, be decisive, ceteris paribus, to the return of the debt-to-GDP ratio to a downward path.

During 2024, the stock of Italian government bonds held by the Eurosystem was reduced by approximately €64 billion compared to the end of 2023. As a result of the end of reinvestments of principal repayments on the entire securities portfolio, gross issues of government bonds net of Eurosystem programmes in the secondary market are estimated to increase by €12 billion compared to 2024. The net flows of securities to be absorbed by private investors, equal to net issues of government bonds net of Eurosystem programmes in the secondary market, will continue to increase in 2025, to a level of around €177 billion.

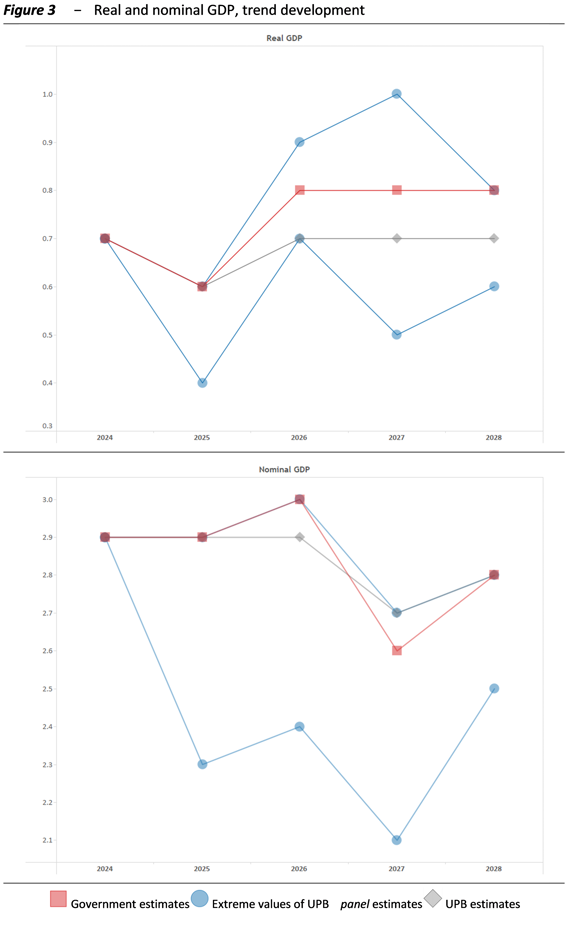

Sensitivity of the debt-to-GDP dynamics. The Parliamentary Budget Office (PBO) has conducted a sensitivity analysis with respect to the debt-to-GDP projections included in the PFD. In this context, an alternative scenario (the “PBO scenario”) was developed, wherein the primary balance and short- and long-term interest rates envisaged in the PFD were recalibrated for the 2025–28 period, taking into account the differentials between the PBO’s projections, formulated during the validation process, and those of the PFD regarding real GDP growth, the GDP deflator, and the consumption deflator. The PBO scenario assumes the same stock-flow adjustment as that underlying the debt dynamics projected in the PFD, which includes for 2027 a contribution from privatizations equal to 0.5 per cent of GDP, a key factor for ensuring a reduction in the debt ratio in that year.

Over the 2025–28 period, the debt trajectory under the PBO scenario is broadly aligned with the path projected in the PFD, with minor deviations mainly attributable to slightly lower nominal GDP growth and a smaller primary surplus compared to the government estimates. The debt-to-GDP pattern under both the PFD and the PBO scenario remains consistent with the trajectory outlined in the MTFSP. Furthermore, a probabilistic analysis, based on the generation of a large number of stochastic scenarios, highlights that the probability of a year-on-year decline in the debt ratio stands at approximately 40 per cent for the current year, decreasing to 15 per cent in 2026. In 2027, this probability increases to around 55 per cent, reflecting the relatively favorable contribution of the stock-flow adjustment included in the PFD, and rises further to slightly above 75 per cent by 2028.

Based on a set of technical assumptions, the debt-to-GDP ratio in the PBO scenario was projected over the medium term, up to 2041, and compared with the corresponding projections contained in the MTFSP. In the medium term, the debt-to-GDP ratio in the PBO scenario is projected to decline at a slower pace than that envisaged in the MTFSP, primarily due to more conservative assumptions on real GDP growth after 2027. According to the MTFSP projections, the debt ratio would decline to 113.7 per cent of GDP by the end of the projection horizon, while under the PBO scenario it would converge to a level close to 118 per cent, still marking a reduction of over 17 percentage points relative to its 2024 starting level.

The Public Finance Document (PFD) in the context of new EU Fiscal Rules. On 26 November of last year, the European Commission assessed the net expenditure path presented in the MTFSP as consistent with all requirements set forth by the reformed EU fiscal framework. The EU Council subsequently approved the Italian MSP on 21 January 2025, establishing the maximum nominal growth rate of net expenditure that Italy should comply with in its medium-term budget planning, both on an annual and cumulative basis (considering 2023 as the baseline year). On an annual basis, the net expenditure growth should not exceed 1.3 per cent in 2025, 1.6 in 2026, 1.9 in 2027, 1.7 in 2028 and 1.5 in 2029. The same path is recommended to put an end to the excessive deficit situation by 2026.

It should be emphasised that the control account that should keep track of annual deviations from the net expenditure path recommended by the Council will be set up from 2026 onwards, based on outturn data for 2025. Although the 2024 is a transition year towards the new EU fiscal framework, its outcome is important because it contributes to the cumulative net expenditure growth rate for 2025, considering 2023 as the baseline year.

According to the PFD, net expenditure growth in 2024 was negative (-2.1 per cent), slightly better than the MTFSP target (-1.9 per cent). This resulted from the sharp decline in primary expenditure following the phasing out of the Superbonus, only partially offset by the growth in the other expenditures that must be subtracted from primary expenditure and the positive impact of DRMs.

For 2025, the PFD reports net expenditure growth of 1.3 per cent, in line with the Council’s recommendation. Unlike 2024, primary expenditure growth contributes positively to the increase in net expenditure, while expenditures to be subtracted from primary expenditure and the DRM effect contribute negatively. The cumulative change in net expenditure for the 2024-25 is estimated at -0.9 per cent, 0.2 percentage points below the maximum rate recommended by the Council.

For the 2026-28, the PFD confirms the net expenditure growth rates proposed in the MTFSP and then adopted by the Council: 1.6 per cent in 2026, 1.8 in 2027 and below 1.7 in 2028. In 2026, the most significant contribution to the indicator’s growth is expected to come from primary expenditure, however counterbalanced by the increase in expenditures to be subtracted from the net expenditure indicator, mainly linked to the increase in NRRP-related interventions. In 2027, the contribution from primary expenditure growth will decline significantly.

The PDF does not provide sufficient information to fully assess the consistency of net expenditure trends after 2025 with the path approved by the Council nor with the criteria on nationally-financed public investment that enabled the extension of the fiscal adjustment period to seven years.

Public finance implications of EU defence initiatives. In the hearing, a descriptive analysis of defence expenditure in Italy compared to other EU countries is presented. The analysis uses two different data sources that differ in the scope of expenditure considered and the timing of recording. The first source is Eurostat data based on the European System of Accounts (ESA 2010), using the COFOG classification and following accrual accounting principles. The other source is NATO data, which encompasses a generally broader scope of defence expenditure and is recorded primarily on a due-for-payment basis.

According to the COFOG classification, in 2023 (latest available year) defence expenditure in Italy amounted to 25.6 billion euros, equivalent to 1.2 per cent of GDP. The evolution of Italian defence expenditure from 1995 to 2023 was relatively stable as a share of GDP around this value. Italy’s defence expenditure as a share of GDP was slightly below the EU average of 1.3 per cent. Member States allocating greater resources to defence relative to GDP were the Baltic countries (Estonia, Lithuania and Latvia) followed by Greece and Poland.

NATO data offer more detailed information on defence expenditure and more updated figures: according to this source, Italy’s defence expenditure in 2024 represents 1.5 per cent of GDP, a value that has increased over time compared to 1.1 in 2014. On the basis of the NATO definition, the composition of Italy’s defence expenditure has changed over the last decade, reducing the share absorbed by personnel expenses (from 76.4 per cent of total expenditure in 2014 to 59.4 in 2024) and almost doubling the share allocated to major equipment, including related R&D and infrastructures. In its 2024-26 Programming Document, the Ministry of Defence confirms its commitment to gradually achieve the 2 per cent of GDP target by 2028.

In response to the evolution of the geopolitical situation, the European Commission has proposed several initiatives to strengthen the defence capabilities of its Member States in a coordinated manner. The ReArm Europe Plan/Readiness 2030 is based on five pillars: the activation of the national escape clause of the reformed SGP; a new dedicated financial instrument (Security Action for Europe – SAFE); the mid-term review of cohesion policy with the reprogramming of funds towards the EU’s new strategic priorities; a renewed role for the EIB in financing defence projects and the acceleration of the Savings and Investments Union. A key element of the Commission’s initiative is, indeed, the proposal to activate the national escape clause that would allow Member States to deviate up to 1.5 percentage points of GDP per year over the period 2025-28 from the Council’s recommended net expenditure limits, provided that such deviation is intended to finance defence expenditure. An important criterion for granting the activation of this clause will be that the flexibility requested by the Member State does not jeopardise medium-term debt sustainability.

Two scenarios have been carried out by the PBO. In the first scenario, it is assumed that Italy makes limited use of the margin for deviation provided by the safeguard clause, amounting to 0.25 percentage points of GDP in 2025 and 0.5 percentage points annually over the 2026–2028 period. Under this scenario, the resulting increase in defence expenditure would allow Italy to exceed, in the short term, the current NATO target of allocating at least 2 per cent of GDP to defence spending.

In the second scenario, it is assumed that Italy makes use of the safeguard clause for an amount equal to 0.25 percentage points of GDP in 2025, as in the first scenario, followed by a gradual increase to 0.6 in 2026, 1.0 in 2027, and 1.5 in 2028, the maximum allowed under the clause. This scenario would be consistent with a medium-term objective of allocating public expenditure to the defence sector equal to or exceeding 3 per cent of GDP.

Furthermore, for the 2029–2031 period, the simulations assume that the structural primary balance adjustment returns to the path set out in the SBP, averaging 0.5 percentage points of GDP per year.

The results show that the use of fiscal flexibility would lead to an increase in the debt-to-GDP ratio from 2025 to 2028, the final year of safeguard clause activation, compared to the trajectory projected in the PBO scenario.

In the years following, as the expansionary impact of higher defence spending on GDP growth fades, the gap between the scenarios with fiscal flexibility and the PBO baseline scenario widens. During the 2032-2041 decade, public debt under the first scenario would continue to decline relative to GDP, although at a much slower pace than that projected in the MTFSP. By the end of the projection horizon, the debt ratio would reach approximately 125.4 per cent of GDP, compared to 113.7 per cent in the MTFSP.

By contrast, in the second scenario, after a brief decline, the debt-to-GDP ratio would resume an upward trajectory, reaching 138.9 per cent of GDP in 2041, over 25 percentage points higher than the level projected in the MTFSP.

Moreover, the activation of the safeguard clause could result in a delay for Italy to exit the EDP. In the first scenario, the general government deficit would fall below the 3 per cent threshold in 2027 instead of 2026, as foreseen in the PFD. In the second scenario, this would not occur until 2030. Additionally, the gradual reduction in the cyclical component of the primary balance, due to the assumed closure of the output gap, and the increase in age-related spending would lead to a progressive rise in the deficit-to-GDP ratio, which, starting from 2034, would remain persistently above the 3 per cent threshold (Figure 4).