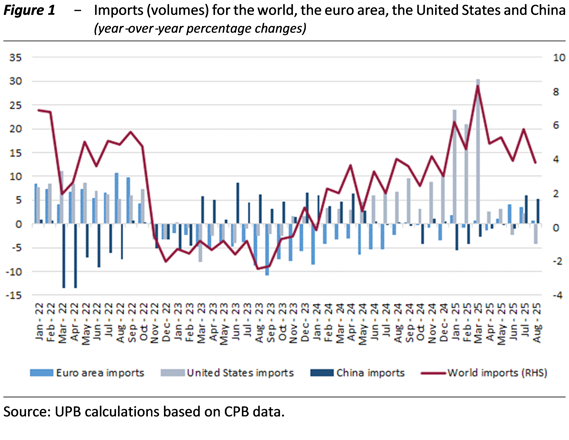

6 November 2025 | Global trade appears to be resilient to protectionism and geopolitical tensions, though the transmission of the new tariffs to the macroeconomy is not yet complete. During the first eight months of the year, world trade grew by just under 5 per cent—more than expected—largely owing to the front‑loading of purchases by U.S. importers in the winter months in order to elude the forthcoming new trade barriers. The United States recorded a sharp increase in imports, the euro area a moderate rise, and China a decline (Fig. 1). Given the tightening of customs duties, a slowdown is nevertheless expected in the second half of the year.

The competitiveness of European production is being held back not only by tariffs but also by the exchange rate. In the summer the United States imposed new duties on European goods: a base rate of 15 per cent for most products—including automobiles and alcoholic beverages—with certain exemptions. If fully passed through to prices, these duties imply a loss of price competitiveness for European products, with significant repercussions for export‑oriented economies such as Germany and Italy. The effect is amplified by the appreciation of the euro, which has strengthened by about 13 per cent against the U.S. dollar since the start of the year.

The short‑term global outlook is moderately favorable and central banks remain cautious. The IMF has revised up slightly its 2025 GDP outlook for the major economies but has marginally downgraded prospects for the euro area in 2026. The pace of global trade in the current year is similar to 2024, but a marked deceleration is projected for 2026. Oil and natural‑gas prices have been decreasing since the beginning of the year, though with volatility. Against this backdrop, the European Central Bank (ECB) kept policy rates unchanged in September and October as inflation hovers around the 2 per cent objective. By contrast, the Federal Reserve cut interest rates again in October—its second consecutive 25‑basis‑point reduction—to safeguard labour‑market conditions.

The Government’s assumptions for international exogenous variables are acceptable but highly uncertain at this stage. The 2026 Draft Budgetary Plan (DBP) adopts the macroeconomic projections of the 2025 Public Finance Planning Document (DPFP), thereby confirming the same assumptions on exogenous variables. World trade growth is envisaged to remain at 2.7 per cent this year, with a sharp slowdown in 2026 due to tariffs; trade should return to growth over the following two years at rates similar to those projected for 2025. As far as other variables are concerned, market conditions currently point to more favourable oil prices than assumed in the DPFP, while the exchange rate is barely unchanged. Overall, the MEF’s macroeconomic assumptions—formulated about six weeks ago—still appear broadly consistent with the latest information. However, significant downside risks persist in the international environment due to geopolitical tensions and to the fact that the effects of U.S. protectionist policies have not yet fully propagated.

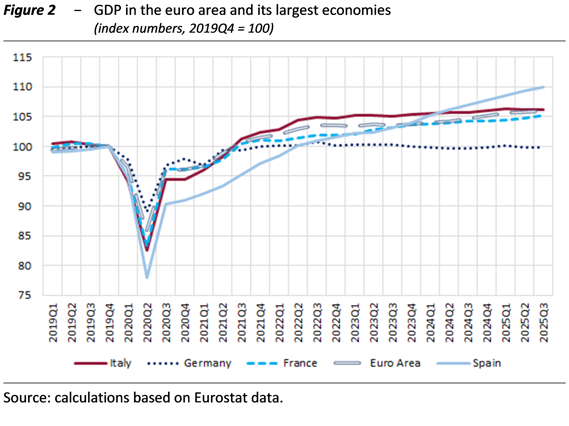

In Italy, the cyclical phase is stagnant, whereas it is moderately expansionary in the euro area. Italy’s GDP edged down in the second quarter and was steady in the third, confirming a pace of growth below that of the euro area (up 0.2 per cent). The summer stagnation reflects an increase in agricultural value added offset by a decline in aggregate industry and construction, with services broadly unchanged. On the demand side, a negative contribution from domestic demand net of inventories was balanced by a positive contribution from net exports. The carry‑over for the year is 0.5 per cent; in annual (non‑working‑day‑adjusted) terms, this implies a weaker increase in 2025 than quarterly data would suggest. In the summer quarter, Spain and France posted robust quarter‑on‑quarter growth (0.6 and 0.5 per cent, respectively), while Germany was flat. Activity levels in Italy are above pre‑pandemic readings by a magnitude similar to the euro‑area aggregate, although Italy’s sequential growth has not outpaced the euro area over the last seven quarters (Fig. 2).

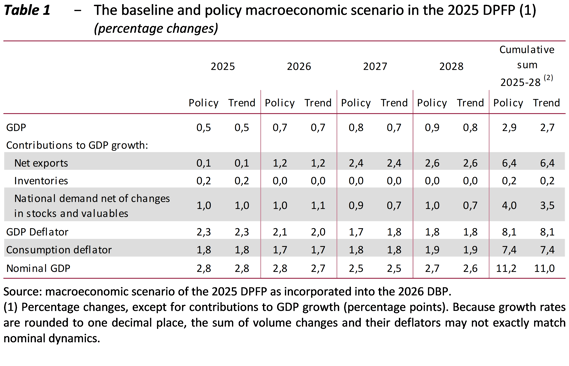

The MEF’s macroeconomic projections—both the trend and the policy scenario — were endorsed by the PBO last month, during the hearing on the 2025 DPFP; the government forecasts, are considered acceptable though exposed to several downside risks. Last week, Istat released the preliminary estimate of GDP for the third quarter of this year, pointing to stagnation. The carry‑over is 0.5 per cent; therefore, the Government’s 2025 growth estimate appears attainable, although calendar effects could subtract a tenth of a point.

The budget package exerts a moderate expansionary effect: the overall impact on GDP reported by the MEF—neutral next year and marginally positive in 2027‑28—over the full horizon is consistent with the PBO’s estimates. In the Government’s projections, the package lifts GDP growth by 0.1 percentage points both in 2027 and 2028. The PBO simulations based on the MeMo‑It econometric model indicate a similar cumulative effect (0.2 percentage points), with a different timing: 0.2 percentage points in 2027, 0.1 in 2028, and a slightly negative impact in 2026 (‑0.1 per cent). These estimates—based on the draft Budget Bill submitted to Parliament on 22 October—match those previously obtained by the PBO, with less detailed information; the previous estimates, made for the endorsement exercise of the MEF’s macro scenario, were presented at the 8 October parliamentary hearing of the PBO on the DPFP.

In the PBO scenario, budget measures affect domestic demand in a manner broadly similar to the MEF’s scenario. The package reshapes capital expenditure—mainly public investment—reducing it next year relative to the trend scenario and then increasing it over the subsequent two years. This rephasing restrains activity in 2026 while supporting growth in 2027, when the economy is also stimulated by lower direct taxes on income; in 2028 the impulse moderates slightly and is still driven by domestic demand. As for foreign trade, exports would remain broadly unchanged relative to the no‑policy‑change scenario over the assessed period, while imports would strengthen, spurred by higher consumption (public and private) and capital spending. The effects on price variables are overall negligible, except for an increase in the private‑consumption deflator in 2026 due to higher indirect taxation.

The DBP’s programmatic macroeconomic forecast lies within the range of recent expectations by other institutions and private analysts (Tab. 1). The Government’s real‑GDP projections are aligned with those—some very recent—of other public and private organizations. With regard to the GDP deflator, which contributes to nominal‑GDP dynamics and is therefore relevant for public‑finance projections, the MEF’s macroeconomic policy scenario falls within the interval reported by other forecasters, although many publish only consumer‑price inflation and not the GDP deflator.

Forecast risks are mainly tilted to the downside. Geopolitical tensions, ongoing conflicts and protectionist policies weigh on the economy with effects that are difficult to quantify; the PBO estimates that U.S. tariffs alone could reduce Italy’s GDP by more than half a percentage point, without considering potential long‑term structural effects on global value chains. Industrial exporters are particularly affected by economic uncertainty in Europe. However, higher spending on defence and infrastructures—especially in Germany—could constitute an upside risk. Construction investment may be affected by the temporal concentration of measures financed by NGEU plan, which may create bottlenecks and curb growth. Residential investment is also uncertain owing to the scaling‑back of the extraordinary public support implemented in recent years. In the financial sector, despite monetary easing by central banks, the fragile international environment could trigger abrupt changes in risk appetite, with adverse effects on the Italian economy, which is characterised by high public debt. Finally, climate change is an increasing structural risk: extreme weather events affect prices and productive capacity and compel public institutions and private operators to invest in prevention and emergency management.

The financial impact of the budget plan

Public‑finance framework in the DBP. — Over the 2026–2028 period, the net‑expenditure path presented in the 2026 Draft Budgetary Plan confirms its compliance with the Stability and Growth Pact. Net expenditure is projected to grow by 1.3 per cent in 2025 and 1.6 per cent in 2026, within the limits recommended by the EU Council. The general‑government deficit declines progressively from 3 per cent in 2025 to 2.3 per cent in 2028. The debt‑to‑GDP ratio reaches 137.4 per cent in 2026 and then begins to decline.

As for the components of net expenditure, in 2026 primary spending contributes 2.8 percentage points to the indicator’s growth, partly offset by the dynamics of EU transfers and other components deducted from primary spending under the European methodology. The plan under consideration adjusts the growth of net expenditure downward by 0.1 percentage points compared with the no‑policy‑change scenario, confirming the SGP objective and in line with the annual expenditure ceiling recommended by the Council.

Overall impact of the plan. — The public‑finance plan, implemented through the measures in the 2026 draft Budget Bill, increases the deficit relative to the baseline over 2026–28 to a rising extent. Including higher interest spending and funding linked to the proposed rephasing of the NRRP submitted to the European authorities, the plan raises general‑government net borrowing by 0.04 percentage points of GDP in 2026 (0.9 billion), by 0.2 points in 2027 (5.9 billion) and by 0.3 points in 2028 (7.0 billion) relative to the baseline. This impact is consistent with the planned deficit‑to‑GDP targets set out in the 2025 DPFP and the 2026 DBP, equal to2.8 per cent in 2026, 2.6 per cent in 2027 and 2.3 per cent in 2028.

The effects of the draft Budget Bill on net expenditure will be provided in the Technical‑descriptive Note; they may differ from those on net borrowing, especially because of one‑off measures—mainly on the expenditure side—with an impact concentrated in 2026. In particular, the net‑expenditure indicator should not be affected by the costs related to emergency spending and to the establishment of the fund to address the financial effects arising from national and EU litigation.

Impact on recipient sectors. — The hearing provides an analysis of the plan by recipient sectors, using the economic base of revenues and the functional classification of expenditures. A lack of information on the proposed rephasing of the NRRP prevents a complete assessment of the overall impact on sectors and on the functional classification of spending.

The analysis shows net benefits for households totalling €18.6 billion over 2026–28. In particular, the net benefit amounts to €6.4 billion in 2026, €7.5 billion in 2027 and €4.7 billion in 2028, reflecting tax‑relief measures and interventions in the social, pension and family‑support areas, in addition to the refinancing of the National Health Service.

General measures—addressed to multiple types of individuals or the economy as a whole—also provide net benefits of €0.6 billion in 2026, €3.5 billion in 2027 and €4.8 billion in 2028. Conversely, measures affecting firms and the self‑employed contribute to the improvement of the deficit by €1.0 billion in 2026, €4.3 billion in 2027 and €2.1 billion in 2028.

In the three-year period 2026–28, the measures reduce the tax burden on labour, against an increase in revenue from capital taxation and, to a lesser extent, consumption taxes. On the expenditure side, the largest net increases concern social protection, economic affairs and healthcare, while savings are concentrated in the group of expenditures not clearly classifiable.

General considerations on the budget plan. – The draft Budget Bill appears consistent with the multi‑year consolidation objectives already set out in the 2025–29 Medium -term-fiscal-structural Plan, approved by the EU Council in January.

Achievement of the objectives depends significantly—particularly in 2026—on funding from the proposed rephasing of the NRRP submitted to the EU authorities. The proposal has not yet been approved at European level. Moreover, neither the draft Bill nor the accompanying documentation specify the projects and spending programs involved in the rephasing, nor the breakdown of resources between revenues and expenditures and, within the latter, between current and capital items. Given these uncertainties, the funding could have included a specific safeguard clause to protect the effects on balances.

For 2027, the new measures have used all the available space in terms of deficit and net expenditure: unless favourable deviations in previous years will be recorded, any future policy proposals will require funding through higher revenues or structural spending cuts. Unless the dynamics of net expenditure for 2025–26 improve relative to projections—developments that would feed into the control account under the new EU rules—the next Budget Bill will necessarily have to associate new measures with structural financing.

Confirming last year’s change in orientation, several major measures—such as the reduction of the central PIT (Irpef) bracket—are structural; alongside these, there are a number of temporary provisions that, if confirmed, will require refinancing and new funding. Among the most relevant temporary measures—already funded in the past and for which resources would have to be found in the future if confirmed—are: the refinancing of the SEZ tax credit; the increase in the fund for purchases of basic foodstuffs; the further postponement to 1 January 2027 of the tax on single‑use plastic products and of the consumption tax on sweetened beverages (the so‑called plastic and sugar taxes).

Several revenue‑raising measures have initially positive, but subsequently negative, effects and therefore do not provide structural resources. For example, the reintroduction of the measures —already adopted for 2025–26 in the previous Budget Law—deferring additional portions of deductions for previous years (DTAs) will generate additional revenues of about 1.8 billion in 2027, followed by a corresponding reduction in 2029–30 when the recovery occurs. Similarly, the two‑percentage‑point increase in the IRAP rate for banks and insurance companies is limited to the tax years 2026–28 and yields positive effects only up to 2029, hence not providing permanent resources.

As to the funding through expenditure reductions, for Ministries, savings still rely largely on across‑the‑board ‘linear cuts’ rather than on a rationalisation effort grounded in policy‑evaluation activities. The activities that should stem from effectiveness and efficiency analyses of public spending have yet to find concrete application in terms of a better allocation of public resources. In line with the reform in the 2025–29 Medium -term-fiscal-structural Plan, the draft Bill takes a first step towards the actual implementation of expenditure assessment analysis by requiring each Ministry, by mid‑2026, to evaluate one policy under its responsibility.

Finally, a number of risk factors characterise the macroeconomic scenario and entail uncertainties for the public accounts: uncertainties in the international environment, potential bottlenecks from the temporal concentration of NRRP investments, the resilience of residential investment, and the need to identify significant resources for the prevention and management of climate and environment related emergencies.

The main measures contained in the budget package

The revision of personal income tax (Irpef). – The Bill continues the reform path launched with Legislative Decree 216/2023, implementing the enabling law on tax reform and consolidated with the 2025 Budget Law. The second bracket rate is reduced by 2 percentage points, to 33 per cent. At the same time, to limit gains for higher‑income taxpayers, a mechanism is introduced to curb tax credits for taxpayers with total income above €200,000, consisting of a flat €440 reduction—the same as the maximum gain from the rate cut. The change is part of a strategy to progressively reduce the tax burden on middle incomes, alongside measures already introduced for employees through enhanced bonuses and deductions.

According to UPB microsimulation estimates, the rate cut would affect about 13 million taxpayers at a cost of some €2.7 billion. The benefit rises with income between €28,000 and €50,000 and then flattens (maximum saving €440). In terms of the average tax rate, the reduction peaks at 0.8 percentage points around €50,000 and diminishes at higher incomes. The distribution of gains is concentrated: about 50 per cent of the resources accrue to the top 8 per cent of taxpayers.

The share of beneficiaries varies across categories: 96 per cent of managers, 53 per cent of white‑collar employees, 37 per cent of the self‑employed, 27 per cent of pensioners, and 16 per cent of blue‑collar workers. In absolute‑value terms, managers receive the largest average benefit (€408, close to the theoretical maximum of €440). Employees and the self‑employed gain €123 and €124 on average, pensioners €55, and blue‑collar workers €23. In aggregate, employees capture the highest share of total benefit (39.7 per cent), followed by pensioners (27.6 per cent) and by the self‑employed (13.4 per cent). The blue‑collar workers absorb 10.3 per cent of total benefit, whereas managers – though receiving the highest average benefit – only 5.5 per cent, given their limited numerosity. The reduction in the average tax rate ranges from 0.1 percentage points for blue‑collar workers to 0.4 for employees and the self‑employed; for managers it is 0.3 despite the larger benefit in absolute terms, given their higher incomes.

As regards deductions, the new flat reduction interacts with constraints introduced in recent years, which limit its effectiveness in offsetting benefits from the rate cut at high incomes. Combining the €440 reduction with previous limits, UPB’s microsimulation suggests that the measure materially affects only 58,000 taxpayers (32 per cent of those with income above €200,000), with an average effective cut of €188—well below €440. The recoverable resources would amount to €11 million, compared with €79.2 million needed to fully neutralize the rate‑cut gains above €200,000. The average net gain for taxpayers over €200,000 remains about €379, close to the theoretical maximum of €440. Over time, the cut tends to shrink further owing to the interaction with the deduction reform enacted in the 2025 Budget Law.

The proposed reform comes after an unusually frequent sequence of changes to Irpef that have substantially reconfigured the tax through incremental adjustments, each responding to specific policy issues. One, in particular, is significant: measures introduced to offset the loss of purchasing power of employees – initially temporary – were progressively strengthened, extended and then stabilized, being embedded into Irpef through specific deductions and bonuses by the 2025 Budget Law. The assessment of the DDLB changes must therefore consider this broader transformation of personal income taxation.

For three representative cases (employee, pensioner and self‑employed worker, without dependants, additional deductions or other income), the cumulative distributional effects of the set of measures were reconstructed by comparing the system entering into force in 2026 with that in place in 2021.

For employees, past measures delivered benefits mainly to low‑ and middle‑income brackets, with an incidence exceeding 6 percentage points at the bottom. The new DDLB reform, concentrated on middle‑high and high incomes, is complementary, reducing the gap where earlier measures had smaller effects. In incidence terms, the overall profile still shows much larger reductions at low and middle incomes, tapering off as income rises. For pensioners and the self‑employed, the effects are smaller and focused on middle‑high and high incomes; the DDLB overlaps with previous reforms, further increasing benefits in those brackets.

Progressivity for employees now depends primarily on specific deductions and bonuses, whereas for pensioners and the self‑employed it reflects the structure of Irpef rates and brackets, yielding markedly different distributions of effects. This differentiation among income‑type regimes is not easily justified by horizontal‑equity criteria and raises questions about the coherence of the tax system.

Given the sharp inflation in 2022-23, evaluating the redistributive effects of Irpef reforms also requires considering fiscal drag. For the three cases, the tax due in 2026 (under the DDLB) was compared with what would have been paid had the 2021 system been fully indexed since 2021. This identifies which income brackets receive relief greater or smaller than the recovery of fiscal drag and isolates policy choices from purely technical indexation.

For employees with taxable incomes between €10,000 and €32,000, the post‑reform system yields lower average tax rates than those under a merely indexed 2021 system, indicating that the reforms were more generous than pure indexation. The opposite holds between €32,000 and €45,000. Above €45,000 the difference becomes gradually negligible, although the post‑reform average rate remains slightly higher.

For pensioners, for most of the income distribution, the post‑reform system produces higher average rates than a merely indexed 2021 system, with the difference narrowing as income rises. Only above €40,000 does the sign reverse; the gap then tends to vanish at higher incomes. A similar pattern is found for the self‑employed. Overall, the reforms have benefited pensioners and the self‑employed only to a limited extent, concentrating redistributive effects primarily on employees via revised deductions and specific bonuses.

The analysis extended to the entire population with the UPB’s microsimulation model shows that the 2021-26 reforms enhanced Irpef’s redistributive capacity relative to a counterfactual with full indexation of the 2021 system. The increase stems mainly from higher progressivity, largely driven by measures favoring low‑ and middle‑income employees, outweighing opposite‑sign effects for pensioners and the self‑employed.

Finally, part of the section discusses the temporary tax relief on wage increases arising in 2026 from contracts renewed in 2025-26. In 2026, absent further support for low‑ and middle‑income brackets, the taxation of pay rises risks being particularly burdensome because recent reforms have raised Irpef’s income elasticity where many employees are located. At €20,000 of income, the elasticity is above 6: a 5 per cent pay rise raises tax by more than 30 per cent (at €30,000, with elasticity 3, the same pay rise raises tax by 15 per cent).

The tax relief therefore aims to curb the marginal levy in this specific context but raises questions about sustainability and consistency with equity and rationality principles. The measure is temporary – limited to 2026 pay rises – thus merely deferring a higher levy without structurally resolving it. Repeating it would be difficult, implying differentiated rates for income components accruing in different years and a layering that would complicate administration and reduce transparency. The measure also creates horizontal‑equity disparities.

These critical issues call into question the appropriateness of using the tax system to pursue economic‑policy goals that require selective, time‑bound interventions tied to collective bargaining and industrial‑relations dynamics, at the risk of subordinating equity, neutrality and simplicity to aims that could be better served by instruments outside taxation. A broader reflection could consider managing support for employees’ purchasing power through dedicated tools, separate from tax‑equity logic, which currently accounts for much of progressivity at lower incomes.

Measures concerning businesses. – Business‑tax measures are expected to have an overall positive impact on the public finances of €3.2 billion in 2026, €3.5 billion in 2027 and €1.6 billion in 2028.

Higher revenues derive from measures with transitory effects—temporary interventions expected to yield €2.8, €1.9 and €1.7 billion in 2026-28 – and from revenue bring‑forwards officially estimated at €2.0, €2.6 and €0.4 billion, and, to a lesser extent, from permanent provisions (€1.0 billion in 2026 and €1.4 billion in 2027 and 2028). Total additional revenues of €5.9 billion in 2026, €5.8 billion in 2027 and €3.5 billion in 2028 are thus one of the main sources of financing for the budget, together with funds from the NRRP rephasing.

Lower revenues – €0.5 billion in 2027, €1.0 billion in 2028 and a little over €0.8 billion on average in the three subsequent years – are linked to new investment incentives. For the same purposes, additional expenditures are planned: €2.6 billion in 2026, €1.8 billion in 2027 and €0.9 billion in 2028.

Temporary measures and revenue bring‑forwards mainly concern the financial sector, which accounts for over 82 per cent of the higher revenues in 2026 and almost 76 and 61 per cent in 2027 and 2028, respectively. The former include: (1) revision of the extraordinary levy on banks introduced by Decree‑Law 104/2023; (2) the 2‑percentage‑point increase in the IRAP rate for banks and insurers in 2026-28; (3) limits on the deductibility of interest expenses for the banking sector for tax years 2026-29. The revenue bring‑forwards include: (1) new suspension of deductions connected with the run‑off of the stock of deferred tax assets (DTAs) accumulated up to 2015, especially in the financial sector; (2) extraordinary recognition of reserves in tax suspension; (3) tighter limits on the deductibility of expected‑loss provisions; (4) tax‑favored assignment of assets to shareholders.

The concentration on the sector could be justified by the strong profitability since 2023, driven by the widening of net interest margins resulting from the asymmetric pass‑through of policy rate increases to lending and deposit rates.

Among more structural measures is the decision to modify the dividend‑taxation regime. Here, the objectives are unclear—both regarding rationalization of intra‑group taxation of dividends and capital gains and in terms of international competitiveness.

As regards pro‑investment measures, the Bill reintroduces in 2026 the tax uplift of depreciation allowances for investments in tangible and intangible capital goods and extends for three years the tax credit for investments in Special Economic Zones (SEZs) and Simplified Logistics Zones (SLZs). Further measures include refinancing ‘Nuova Sabatini’ and introducing a tax credit for investments in agriculture. These incentives entail lower tax receipts and higher spending totalling €2.6 billion in 2026, €2.3 billion in 2027, €1.9 billion in 2028, €0.9 billion in 2029 and €0.8 billion annually in 2030-31.

The DDLB is consistent with previous goals of fostering investment in capital goods for technological and digital transformation (4.0 goods) and in goods to reduce energy consumption (5.0 goods). However, for 2026 it reverts to the uplift of depreciation allowances, which had been replaced in 2020 by tax credits, with significantly higher incentive rates than those in force in the years 2023-25. For 4.0 goods, the uplift rates are slightly higher than in 2019 (the last year of the previous regime). However, for tangible assets, the implicit incentive rate – measured as the ratio between the present value of tax savings and the investment cost – is markedly higher than that for 4.0 goods under the 2023-25 regime and for 5.0 goods in 2024 and 2025. The enhancement is even more evident for intangible assets, which historically benefited from lower incentive rates and were excluded from the 2025 tax credit. That said, the higher potential intensity of the incentive must account for the different nature of the uplift—which reduces the tax base—versus tax credits.

Replacing tax credits with deduction‑based uplifts has pros and cons for firms and differentiated effects on the public accounts.

Firms, while benefiting from simpler access to the incentive than under a tax credit, will only obtain the benefit (a tax reduction) not immediately but over a period determined by the average useful life of the investment assets, and only if they have adequate tax capacity—that is, sufficient profitability. The first aspect reduces the effectiveness of the incentive both because the benefit is deferred relative to the investment and because it is more uncertain, being tied to the firm’s profitability expectations. The second aspect exposes the instrument to the risk of deadweight loss, favoring firms that are in a stronger economic position and would have undertaken the investments even in the absence of the incentive.

Moreover, relying on deductions rather than tax credits may penalise large multinational groups located in Italy relative to other firms under the 15 per cent Global Minimum Tax introduced in Italy from 2024. In particular, in the context of international tax arrangements, non-qualifying incentives – including exemptions and deductions – have a greater impact than cash subsidies and qualifying tax credits on the calculation of effective tax rates (ETR). In the presence of incentives, the ETR may fall below 15 per cent – even with a 24 per cent statutory rate – thus triggering the payment of a top-up tax.

By contrast, the use of enhanced depreciation offers some advantages when budgetary constraints are binding, owing to its accounting treatment relative to tax credits. For a given envelope of resources, deductions are more conducive to public-finance control, since they do not concentrate the cost in a single year – as tax credits do – but spread it across several fiscal years. This facilitates the management of annual budget balances and compliance with EU fiscal rules.

The Bill extends the SEZ/SLZ investment tax credits for 2026-28 with total resources of €2.4 billion in 2026, €1.1 billion in 2027 and €0.9 billion in 2028. Maximum incentive rates range from 15 to 70 per cent, with specific percentages for small, medium and large firms. Spending caps and very high demand could reduce ex‑post rates, risking the neutralization of incentives for additional investment and turning the measure into a subsidy for projects already planned. In 2024, for example, the ex‑post rate was cut to 17.3 per cent of the original credit.

In short, the incentives in the Bill appear to significantly reduce the user cost of capital – more than policies in recent years – also thanks to strengthened 5.0 goods measures. However, the measures remain exposed to several factors that may dilute their stimulus effect.

At a broader level, the measures do not appear to reflect a fully coherent design and consistent with the enabling tax‑reform law.

The two‑point increase in IRAP rates for financial and insurance firms – even if limited to 2026-28 – runs counter to the perspective of abolishing the tax (envisaged by Article 8 of the enabling law). Abolishing IRAP has been discussed since its introduction in the late 1990s but has never been achieved, although several measures have progressively reduced the taxable base. The difficulty in foregoing the tax is linked to its revenue size (about €30 billion in 2023) and its role as the main regional tax and a key source of health‑care financing.

Finally, the Bill neither renews nor replaces the Ires “premiale” introduced only for the current year by the 2025 Budget Law. After the abolition of the ACE from 2024, a revision of corporate taxation that reinstates neutrality across sources of finance and sets out the new investment incentive mandated by the enabling law has yet to take shape.

Overall, with regard to businesses the Bill seems to prioritize short‑term goals (temporary levies and revenue bring‑forwards) over structural interventions. The effectiveness of investment incentives is reduced by the choice of less immediate and certain instruments compared with tax credits – albeit consistent with public‑finance constraints. The concentration on the financial sector, while perhaps justified on a conjunctural basis, raises questions about the distribution of the tax burden and revenue stability in subsequent years, when temporary measures expire and the recovery of bring‑forwards takes place.

Measures in the pension field. – The Bill modulates the three‑month increase in age and contribution requirements for retirement: in 2027 the increase will be one month and in 2028 a further two months, excluding workers in arduous or heavy‑duty occupations and early‑entry categories. This is a transitional measure and does not alter the automatic linkage of retirement requirements to life expectancy, which is crucial for the long‑term sustainability and adequacy of the pension system.

Beneficiaries are those who meet the (modified) requirements in 2027 and opt to retire. The higher budgetary cost stems from two additional monthly payments of benefits, though ‘windows’ defer the outlay. For 2027-28, the UPB pension model estimates additional spending of €1.54 billion (€1.11 billion in 2027 and €430 million in 2028), consistent with the Bill’s Technical Report. The measure does not impact adequacy and lifetime returns of the public pension plans. The average gross replacement rate and the real internal rate of return over the period 2025-2031 do not display significant deviations, in the two years affected by the measure, from the remaining years of the period. The former indicator follows an upward trajectory until 2029 – attributable to the progressive increase in the retirement age and weak wage dynamics – and then declines in the final part of the period, in line with the gradual transition toward the contribution-related (NDC) system. The real internal rate of return on newly awarded pensions declines steadily between 2025 and 2031, reflecting the combined impact of: (1) the increase in the retirement age, which makes the portion of the pension calculated under the earnings-related rule less advantageous and (2) the growing weight of the contribution-related component, which is less generous than the earnings-related one.

Among the other measures in the Budget Bill is the confirmation for 2026 of the APE sociale, the bridge benefit reserved for specific categories of workers that allows early exit at 63 years and 6 months, as well as the incentive to remain in employment for those who, having met the requirements for early retirement, choose to stay in service and receive in their payslip the employee’s contribution share on a tax-exempt basis. A €20 monthly increase is also provided for social supplements paid to low-income pensioners, replacing and expanding the previous €8 increase limited to 2025.

Overall, the package charts a pension‑spending path compatible with budget‑balance commitments and reconfirms the system’s current set‑up in both the short and the medium‑to‑long term.

Changes to the ISEE. – The Bill amends the Equivalent Economic Situation Indicator (ISEE) calculation for access to and disbursement of the Universal Child Allowance (AUU), the Inclusion Allowance (ADI), the Training and Work Support (SFL), the Nursery Bonus and the New‑born Bonus, and increases the authorized spending for these benefits by about €500 million from 2026.

The changes concern the equivalence scale (introducing a new increment of 0.1 for households with two children, and increasing the increments for households with three, four, and at least five children by 0.05, 0.1 and 0.05, respectively) and the treatment of owner‑occupied principal dwelling within the wealth component (raising the franchise from €52,500 to €91,500 and activating the €2,500 per‑child increase starting from the second child). The first change implies that, for a given income-and-wealth position, affected households will have a lower ISEE and will therefore appear relatively poorer. Two effects follow. First, the number of households eligible for services and benefits to which the proposed changes apply increases. Second, households that were already eligible will, where applicable, receive higher amounts. The second change alters a cornerstone of the indicator’s structure: the equal treatment – with respect to housing costs – that the 2013 ISEE reform ensured between owner-occupiers and renters. Consequently, elements of inequity are introduced by granting households living in owner-occupied dwellings, at the same economic condition and family size, priority in access to benefits and, where applicable, larger benefit amounts.

While one could argue that fixed parameters may need updating after several years, changing just one element – the owner‑occupied franchise – appears to be a specific policy choice favoring certain households. Moreover, cadastral values tend to be more stable than rents, which reflect market conditions.

Using a representative sample of ISEE declarations, a preliminary analysis was conducted on the share of households affected by the regulatory changes—both individually and jointly. The results show that the increase in the owner-occupied housing franchise concerns 21.0 per cent of households, whereas the changes to the equivalence scale affect a significantly larger group, 36.8 per cent. Considering the two measures together, it is estimated that 48.1 per cent of households filing an ISEE—almost half of the reference population—benefit from at least one of the changes introduced.

The increase in the franchise for the principal dwelling benefits 55.2 per cent of households living in owner-occupied housing, indicating that a sizeable portion of these dwellings has a value above the current €52,500 franchise. The share of beneficiaries rises to 72.9 per cent when the effect of the equivalence-scale change is also included.

The equivalence-scale increases involve almost all families with at least two children. By contrast, the increase in the owner-occupied housing franchise displays a weaker—though still rising—relationship with the number of children: the share of affected households goes from 14.9 per cent for those without children to 27.9 per cent for households with two children. The combined effect shows that households with children are the primary target of the intervention as a whole.

Breaking down the results by socio-demographic and economic characteristics of the ISEE declarant (age class, labour-market status, and citizenship) indicates that the joint effect of the two changes is higher for households whose declarant is aged 30-60, self-employed, an Italian citizen, and resident in the North-East in municipalities with 5,000-20,000 inhabitants.

It should be borne in mind that a reduction in the ISEE due to the changes does not automatically translate into higher monetary benefits for the affected households. The actual advantage depends on the design of each programme. The text provides the example of the Universal Child Allowance (AUU), which makes it clear that there will be households benefiting from the ISEE changes without receiving a higher allowance.

The AUU is structured into three ISEE bands. In band A (up to about €17,200), the allowance amount is fixed and corresponds to the maximum value. In band B (between about €17,200 and €46,000), the amount decreases linearly as the ISEE rises. In band C (above €46,000), the minimum allowance is paid.

Beneficiaries of an increase in allowances stemming from the changes introduced by the Budget Bill fall into two categories. The first, numerically limited, comprises households that switch bands: according to UPB estimates, just over 5 per cent of households affected by the changes move from band B to band A, while slightly more than 10 per cent of those in band C move to band B. The second, quantitatively more significant, includes households that remain in band B but receive a higher allowance thanks to the reduction in their ISEE. In this band, because the allowance declines linearly as ISEE increases, a lower ISEE translates into a proportional increase in the benefit. For band B, therefore, the size of the increase depends on the magnitude of the ISEE reduction. By way of example, for a one-child household that fully benefits from the increase in the franchise for the principal dwelling (+€39,000), the ISEE reduction would be roughly €3,300 (0.2 × 39,000 × 2/3 ÷ 1.57, where 1.57 is the equivalence-scale parameter), resulting in an annual AUU increase of about €170 (3,300 × 0.0522, where 0.0522 is the increase in the allowance for every €100 reduction in ISEE in band B). The benefit rises with the value of the dwelling and is maximised when the value exceeds the new €91,500 franchise, allowing the change to be exploited in full. According to the Technical Report estimates, around 2.6 million children in households affected by the measure will see their allowance increase by an average of €10 per month, for a total estimated benefit of €324.1 million.

Measures in the health sector. – The Bill increases the financing of the standard national health‑care requirement by €2.4 billion for 2026 and €2.65 billion per year from 2027. As a share of GDP, financing amounts to 6.1 per cent in 2026, then declines by a tenth of a point per year to 5.9 per cent in 2028.

In absolute terms, the Italian National Health Service (NHS) financing rises from €136.5 billion in 2025 to €142.9 billion in 2026 (an increase of €6.4 billion, of which about €4 billion allocated by previous measures), €143.9 billion in 2027 and €144.8 billion in 2028.

Current health expenditure in national-accounts terms (SNA 2010), as a share of GDP, is projected at 6.6 per cent in 2026; from the following year, the ratio would fall to 6.5 per cent. Over the three-year forecast horizon, the average growth rate (3.2 per cent) is more than double the average annual ceiling for net primary expenditure set in the Structural Budget Plan (1.5 per cent), with the increase concentrated mainly in the first year.

The different dynamics of financing and expenditure imply a widening gap between the two aggregates. These differences do not map directly to an NHS deficit, as they reflect several components – including accounting items – yet they may signal increasing difficulty in keeping Regional Health-Service budgets in balance.

The health package uses, in addition to the newly appropriated funds, the resources allocated by last year’s Budget Law for priority national health objectives – almost €800 million for 2026, just over €300 million in 2027, and nearly €400 million in 2028 – whose finalization is only now being finalized.

Overall, there is no clear prioritization to consolidate the NHS, as resources are spread across many objectives and a wide spectrum of stakeholders. As for the planned hiring programme, it is not guaranteed that efforts to increase the NHS’s attractiveness will suffice to enable the recruitments needed for full functionality.

Several factors exert pressure and raise future staffing needs: the retirement of a larger number of doctors and nurses than in the past (baby-boom effect); high resignations unrelated to retirement; significant outward migration of health professionals trained in Italy (not always offset by opposite flows); and new needs stemming from NRRP implementation. Moreover, general practitioners remain outside the scope of the package, pending the expected reform to regulate their activity within Community Health Houses, while it seems increasingly difficult to maintain an adequate general practitioner-to-patient ratio nationwide.

Finally, the Budget Bill addresses resource monitoring and allocation across Regions through various measures, including the integration of the NHS performance indicator system with permanent monitoring of the balance between NHS financing levels and their changes and the evolution of service levels delivered. This latter provision is difficult to interpret, but it appears to be linked to the foreseen application of one of the allocation criteria set out in Legislative Decree 68/2011, namely the pathway for improving quality standards.

Measures on tax evasion and enforced collection. – Although the propensity to evade is declining, tax evasion remains widely spread. It increases the burden on compliant taxpayers, distorts labor-market choices, and creates conditions of unfair competition among firms, while also diverting resources that could be used to finance productive expenditure. In this context, the Budget Bill intervenes only marginally with measures to reduce tax evasion, while introducing a new facilitated settlement of debts entrusted to the collection agent (“rottamazione quinquies”).

With regard to the former, a new form of automatic VAT assessment is introduced in the event of failure to file the return, based on e-invoices issued and received, electronic receipts transmitted, and information inferred from periodic VAT settlements. The measure aims to make better use of the vast information assets of the Revenue Agency to encourage voluntary compliance and combat evasion. Further limits are also introduced to counter improper set-offs of tax credits.

As for the rottamazione quinquies, it is similar to many previous rounds but differs in certain respects. First, only debts arising from omitted payments and amounts due following the automatic and formal checks of returns by the Revenue Agency are eligible. It is therefore reserved for a group of beneficiaries whose irregularities may stem from economic hardship (not verified, as no selective mechanism is provided) or from errors in filing, excluding taxpayers for whom explicitly evasive conduct has been established. Nevertheless, debts relating to previous tax-peace procedures are admitted, in particular those already covered by the rottamazione quater, even if the taxpayer had defaulted on the instalment plan and lost the associated benefits. Second, the measure is more generous than previous ones because the payment horizon is extended to nine years; however, given the simultaneous requirement of a minimum instalment amount (€100), the amortization path is calibrated to the total value of the debts admitted to the settlement.

The repetition of facilitated-settlement measures for outstanding debts has made the enforced-collection framework increasingly complex, with uncertain results in terms of collections. Nor do these measures appear to have significantly addressed the inefficiencies of enforced collection, with evident consequences for the size and quality of the stock of receivables. As of January 2025, the stock entrusted to collection – increased by 37.6 per cent compared with 2019 – amounted to €1,881.5 billion. Of this, €421.4 billion had been written off or cancelled (+43.4 per cent versus 2019), and only €180.3 billion had been collected (9.6 per cent of the total entrusted). The residual accounting stock amounted to €1,279.8 billion, of which only €101.2 billion related to positions with a higher degree of collectability. It should also be noted that the value of instalments due has increased sharply (+136.05 per cent compared with 2019), indicating greater resort to instalment plans for debt settlement.

Finally, some observations are warranted regarding the effects that repeated deflationary measures have, on the one hand, on the effectiveness of the tax administration’s audit, control and collection activity and, on the other hand, on the overall level of tax compliance. There is a risk that the reiterated introduction of facilitated settlements could, over time, also reduce ordinary collection. On one side, the amount of receivables collectible through ordinary procedures progressively declines; on the other, taxpayers come to rely on the introduction of new or repeated forms of relief on amounts not paid under ordinary procedures. It is therefore positive that the Budget Bill provides that the benefits lapse after non-payment, insufficient payment, or late payment of the single instalment, or of two instalments (even non-consecutive), or – as a new feature compared with previous rounds – of the final instalment.

It would also be advisable not to reintroduce concessions that appear difficult to justify, such as discounts for receivables that would likely be collected under ordinary instalment plans, or the readmission to relief of taxpayers whose benefits under earlier “rottamazioni” had already lapsed. In this respect, the limitations on the types of acts eligible for settlement and the exclusion of those current with payments relating to previous facilitated settlements are appropriate.

The Budget Bill extends to Regions and local authorities the option to introduce, on their own initiative, facilitated settlements for their own taxes, with the exception of IRAP and surtaxes. The possible effects of this option on the stock and on provisions to the Fund for Doubtful Receivables (FCDE)—and, consequently, on these entities’ spending capacity in light of the new EU budget rules—will need to be considered.

The Budget Bill grants local authorities the faculty, and in some cases the obligation, to entrust enforced collection to AMCO S.p.A., which may in turn rely on private operators listed in the register of authorized entities for the liquidation, assessment and collection of local taxes. Over the past decade there has been a progressive reduction in the number of municipalities entrusting their receivables to AdER for enforced and/or voluntary collection, with 55.4 per cent now assigning the service to other agents. Entrusting the function to an additional entity other than AdER would further complicate the local-tax collection landscape, with uncertain outcomes. Managerial complexity could increase further given that some local authorities already entrust both ordinary and enforced collection to AdER and to registered private agents. Carving out the latter for AMCO would raise the number of actors involved, producing a complex framework that may be associated with inefficiencies. Fragmentation across a plurality of operators could prevent the full exploitation of synergies in terms of experience, information assets, and interoperability of the databases needed for efficient collection.

Measures concerning local public finance. – The Bill provides a set of measures that can be grouped under three headings.

The first group includes measures aimed at expanding the fiscal space available to territorial entities. For the Regions, a €100 million reduction in their 2026 contribution to general-government finances is provided with the possibility of a further reduction in exchange for waiving the residual tranche of investment grants, which is, however, partly earmarked for municipalities. Regions may also avail themselves of the cancellation of liquidity advances and health-care debt (€25.068 billion and €6.325 billion, respectively) – where the accumulation of liquidity advances negatively impact on the regions’ operating results in the annual accounts – in return for the obligation to repay the residual shares to the State over the period 2026-2051. This creates, for entities that would result in surplus after the cancellation, greater room to use resources set aside as contributions to public finance for financing investments (€600 million over 2026–2030). The provision nevertheless raises concerns: first, because it applies exclusively to Regions even though liquidity advances were also granted to local authorities; second, because it derogates from harmonized accounting rules for all territorial entities, constraining for a long period the spendability of the accumulated results of the Regions concerned.

For local authorities, additional fiscal space derives from a change in the calculation of provisions to the Fund for Doubtful Receivables (FCDE). The measure incentivizes improvements in collection, allowing entities to rapidly translate such improvements – if not temporary – into lower FCDE provisions, thereby freeing resources for expenditure (the potential increase in spending is estimated at €1,358 million over the period 2026-2031). As already noted, the Bill also intervenes on enforced collection, requiring entities with weak enforced-collection capacity to entrust the function to AMCO S.p.A.

The Bill also increases the spendability of earmarked surpluses for local authorities in deficit that comply with their planned recovery, in order to ensure the use of transfers, especially those earmarked for Essential Levels of Provision (LEP) and fundamental functions. The measure’s effectiveness, however, risks being diluted by the exclusion of the Regions.

The second group comprises provisions jointly involving Regions and municipalities to define LEP and the related financing and monitoring mechanisms in certain areas covered by the completion of regional fiscal federalism – a enabling reform of the NRRP, due to be completed by the first quarter of 2026.

For health and education, the Bill merely refers, respectively, to the Essential Levels of Assistance (LEA) and to the LEP for the right to university study, already defined by sectoral legislation. For the LEP on the right to university study, resources are increased by €250 million per year from 2026. For social assistance, existing LEP are recalled and new ones are established. In addition, the provisions lay the groundwork for integrating the different sources of funding that may contribute to the implementation of the LEP.

In social assistance, for LEP and service targets related to social benefits, a Guarantee System is established at the level of Social Territorial Areas (ATS) to coordinate financing, provision, and monitoring of the essential levels. In addition to bringing existing LEP under the System, new levels are defined: multidisciplinary teams within the ATSs – funded with €200 million per year from 2027 under the FELS – and home care for non-self-sufficient persons of no less than one hour per week, funded under current legislation. With regard to communication assistance for pupils and students with disabilities, new LEP are set for the number of assistance hours linked to Individual Education Plans, for the operation of a registry mapping territorial needs, and for professional standards of the staff involved in communication assistance. For the years 2026-27, pending the survey of actual service needs, a transitional service target is established – particularly for severely under-served areas – of 50 hours per pupil per year, which appears well below potential needs. This communication-assistance LEP is excluded from the Guarantee System provided for LEP in social-benefit services.

The third group of measures in the Bill brings together provisions that create new funds for territorial entities or modify existing ones, while remaining non-systematic and fragmented relative to the mechanisms developed under fiscal federalism. The proliferation of separate funding streams for similar functions, each with different allocation criteria, hampers the reconstruction of total resources and the assessment of policy effectiveness, and weakens existing equalization mechanisms. A more organic approach would require integrating all funding related to municipal functions into the Municipal Solidarity Fund (FSC) and funds aimed at equalizing service levels into the Special Fund for the Equity of Essential Levels of Provision. To keep current equalization mechanisms compatible with the evolution over time of entities’ needs – also owing to contract renewals and inflationary pressures – it would be advisable to periodically review the vertical component of the FSC and the equalization funds for provinces and metropolitan cities within the Structural Budget Plan, in line with the new EU rules, rather than resorting to ad hoc measures through specific funds.