7 May 2024 | The reform of the EU’s framework of fiscal rules —

The negotiations on the reform of the European economic governance have come to an end and on 30 April 2024 the acts that reform the Stability and Growth Pact (SGP) officially entered into force. On 26 April last year, the European Commission presented a proposal for a new Regulation for the preventive arm of the SGP, a proposal for amendments to the Regulation for the corrective arm and a proposal for amendments to the Directive on budgetary frameworks. On 20 December, the Council of the EU (ECOFIN) reached an agreement on the whole legislative package amending the Commission initial proposals. Last February, an agreement was reached between the Council and the European Parliament. On 23 April, the Parliament voted in favour of the new preventive arm regulation, giving a favourable opinion on the other proposals agreed within the Council. The legislative process ended on 29 April with the Council finally approving the legislative package. The regulations reforming the preventive and corrective arms of the SGP are directly applicable to Member States pursuant to Article 288 of the TFEU. On the other hand, the amendments to the Directive on requirements for budgetary frameworks will have to be transposed into national law by 31 December 2025.

Following the reform, Member States will have to submit to the EU national medium-term fiscal structural plans (MTPs) which will be the main multiannual programming tool. The MTPs will replace the current Stability Programmes and the National Reform Programmes spanning over four or five years depending on the length of the national legislature. Therefore, in the case of Italy, the Plan will last for five years.

For countries with a deficit or debt above the Treaties thresholds, the plans will include a fiscal adjustment path ensuring a plausible reduction of the debt to prudent levels in the medium term and the respect of common numerical safeguards for debt and deficit. More precisely, Member States with a deficit above 3 per cent of GDP or a debt above 60 per cent of GDP, will have to include in the Plan an adjustment path such as to ensure at the end of the consolidation period: (I) debt on a plausibly downward trajectory or maintained at prudent levels (ii) deficit below 3 per cent of GDP over the medium term. During the adjustment period (excluding years in which the Member State is in the excessive deficit procedure, EDP), the debt will have to decrease on average by 1 percentage point of GDP per year as long as the ratio remains above 90 per cent. Consolidation will eventually have to continue until the structural deficit will be below 1.5 per cent of GDP. Finally, if Member States are in EDP, consolidation will have to improve the overall structural balance by at least half a percentage point per year. In the three-year period 2025-27, for countries in EDP the increase in interest expenditure as a ratio of GDP will be “taken into account”; thus, the required adjustment of half a percentage point of GDP applies to the structural primary balance (and not to the overall balance).

The adjustment will last four years but it may be extended to seven years if the country commits to structural reforms and investments. Reforms and investments included in the extension request should support an improvement in the Member State’s potential growth and fiscal sustainability, represent a response to the country’s structural difficulties and to the specific recommendations addressed to the country by the Council in the context of the European Semester. Reforms and investments should also contribute to the common EU priorities, including the green and the digital transition, social and economic resilience, with particular regard to the European Pillar of Social Rights, energy security and the strengthening of European defence.

The fiscal adjustment will be expressed with the single indicator of the net primary expenditure financed at national level. The single operational indicator excludes from total expenditure interest expenditure, transfers received from the EU for European programs, national co-financing expenditure incurred for EU-funded projects, expenditure related to the cyclical unemployment benefits, the impact of one-off and other temporary measures. The aggregate will also be calculated net of the impact of discretionary revenue measures.

The plan must be submitted to the European Commission and the Council by 30 April of the last year of the Plan in force. There will be a technical dialogue with the Commission before the drawing up of the plan and a reference trajectory will be indicated by the Commission by 15 January. The adjustment path included in the submitted Plan must be consistent with this trajectory. Moreover, if a seven years adjustment path is submitted, the Commission will have to assess whether reforms and investments meet the criteria for extending the adjustment length. A new government can ask to submit a new Plan. A government still in office will also have the opportunity to revise its MTP if, due to objective circumstances, it is no longer able to comply with it.

In the case of positive evaluation by the European Commission, the Council will adopt the Plan; the net primary expenditure path agreed with the Council will represent a ceiling that the country cannot exceed. A control account shall be established to detect positive and negative annual and cumulative deviations in net expenditure from the annual targets set by the Council.

By 30 April each year, Member States should submit an annual Report to the EU on the state of implementation of the Plan. The annual budgetary surveillance will be based on monitoring the single indicator of the net primary expenditure and its control account. In the event of deviations beyond certain thresholds from the agreed path, the debt-based EDP will be activated. The EDP for non-compliance with the above 3 per cent of GDP deficit criterion has remained broadly unchanged with respect to previous legislation.

The reform does not make any change to what is already contained in EU Regulation No 473/2013 (part of the so-called Two Pack) for the Independent fiscal institutions (IFIs) of the Euro area countries (for Italy, the PBO); they therefore keep the same role as regards the production or endorsement of macroeconomic forecasts of policy documents and the monitoring of national fiscal rules. The reform extends to all EU countries the same role for IFIs as regards the macroeconomic forecasts of the policy documents. In order for IFIs to properly perform this task, the reform extends to all Member States the obligation of common standards of independence and operational capacity for IFIs.

In addition, the reform strengthens the role of IFIs in public finance monitoring. With regard to the preventive arm, the Member State may request the IFI to provide an ex-post assessment on compliance with the net primary expenditure path agreed with the Council. As regards the corrective arm, a Member State in EDP may invite the IFI to submit an independent and non-binding report on the appropriateness of the corrective measures adopted to respond to the Council recommendations in the context of the EDP.

Public finance scenarios in the context of the new regulatory framework: a comparison with the previous rule of adjustment towards the medium-term objective

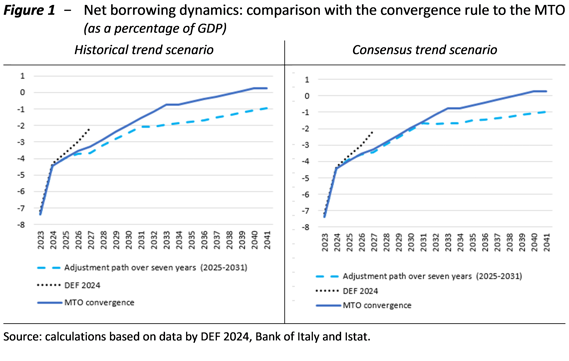

The implications of the new EU economic governance on fiscal consolidation requirements are showed comparing the adjustment over a seven-year period (2025-2031) consistent with the new rules and an adjustment path consistent with the regulations previously in force which, still from 2025, envisages a convergence toward the medium-term objective (MTO).

In the previous convergence criteria toward the MTO, corresponding for Italy to a structural surplus balance of 0.25 per cent of GDP, the magnitude of the annual change in the structural balance was based on several factors such as: whether or not an EDP was open, the conditions of the business cycle and the risks related to the sustainability of public debt. Thus, in the convergence exercises towards the MTO, the annual adjustment of the structural balance corresponds to at least 0.5 percentage points of GDP in the period 2025-28 when net borrowing is above 3 per cent with an EDP therefore open. In the following years, the size of the annual reduction in the structural deficit is determined by the prevailing cyclical conditions using the so-called “annual adjustment matrix”, and it is equal to an annual reduction in the structural balance of 0.6 percentage points of GDP in the case of “normal cyclical conditions” approximated by an output gap of between -1.5 per cent and 1.5 per cent of potential GDP.

With such adjustment, the MTO would be achieved in 2034, both under the assumption of potential growth in line with pre-pandemic levels (“historical trend” scenario, with potential growth equal to about 1.1 per cent), and in the case of potential GDP growth gradually converging to the Consensus (the “Consensus trend” scenario, where potential growth gradually shrinks from 1.1 per cent to 0.7). On the other hand, in the scenario compatible with the new EU governance under the assumption of potential growth in line with the “historical trend”, an annual adjustment of the primary structural balance of 0.5 percentage points of GDP over seven years (2025-2031) and 0.25 percentage points over the three-year period 2032-34 to allow the structural deficit to remain below 1.5 per cent of GDP could represent the minimum consolidation required. In the “Consensus trend” scenario, due to lower potential growth, the annual adjustment of the structural primary balance compatible with the new rules should instead be more ambitious and equal to 0.6 percentage points of GDP over the period 2025-2031.

The analysis shows that, in the MTO convergence scenario with an “historical trend”, both the overall balance and the primary balance are progressively higher than the trajectories consistent with the new EU legislation (Figure 1, left-hand panel). By contrast, under the “Consensus trend” scenario, in the period 2026-2031 the overall balance and the primary balance of the MTO convergence scenario would be on trajectories similar to those resulting in the scenario consistent with the new EU legislation with an adjustment path over seven years (fig.1, right-hand panel). However, under both growth assumptions, net borrowing in the MTO convergence scenario would continue to improve in the following years until reaching a fiscal surplus of 0.25 per cent of GDP in 2040-41, while, in the same years, the net borrowing compatible with the new rules would be around 1 per cent of GDP. Due to the higher adjustment, in the scenarios consistent with the convergence to the MTO the debt ratio in relation to GDP is always around the same or lower than the one resulting from the scenarios consistent with the new EU fiscal framework.

The current-legislation evolution of the net borrowing to GDP ratio reported in the 2024 Economic and financial document (DEF) for the 2025-2027 period appears consistent with the indications of the final agreement on the EU framework in both scenarios.

The new European Semester and the implications for public finance policy documents in Italy

One of the main innovations of the new governance framework is the shift from uniform numerical fiscal rules for all Member States to rules that take into account the country-specific macro-financial characteristics in a context of reinforced medium-term programming. Within this framework, the new economic governance is based on obligations and procedures that allow, on the one hand, Member States to retain discretion over the actions to be taken and, on the other hand, EU institutions to guide and monitor compliance with commitments within the European Semester.

In the context of the European Semester, the new governance framework partly revises Member States’ procedural obligations. As described above, the new regulations require Member States to submit to the EU, normally at the beginning of the parliamentary term, or when a new Government is formed, a Structural Fiscal Plan showing the multiannual policy path of net primary expenditure for the next four or five years. Furthermore, in the context of the European Semester, the monitoring of the MTP’s policy targets shall remain annual with the submission by Member States of an implementation Report on the Structural Fiscal Plan by 30 April each year.

National legislation (in particular L. 196/2009) already recognises the European Semester as one of the bases on which to structure the national budgetary cycle. However, the national budgetary cycle will have to be adjusted to align it with the new EU rule framework. First, it is considered that the MTP should be introduced into the national budgetary cycle as a new policy document to be presented by the end of April every five years in line with the length of the legislature. Moreover, a consideration is needed on whether the content and structure of the DEF (presented in April) and NADEF (i.e. the September update of the DEF) should be changed in order to make these policy documents functional to the requirements of the new EU governance.

The annual presentation of the DEF to Parliament could be maintained but changing its contents. The first part of the DEF may include the information for the previous year required by the annual MTP implementation Report. The second part of the DEF could include the estimation of macroeconomic and public finance developments for the current year and the updating of the trend forecasts for the following years, which would be compared with the corresponding policy objectives foreseen in the MTP. In view of any trend in net primary expenditure exceeding the targets set in the MTP, this part of the DEF should provide a preliminary description and quantification of the main expenditure and revenue measures that the Government intends to implement to bridge the gap for the remaining years. Moreover, the presentation of current-legislation forecasts should also be accompanied by no-policy-change forecasts with a broader informative content than has been published so far. In part three, the new DEF should keep, with additions, the current Section II of the DEF which contains detailed information on public finance trends.

In a context of unchanged net primary expenditure targets with respect to the MTP, the NADEF could also be maintained with the aim of updating the DEF forecasts and presenting the measures to be introduced by the budgetary manoeuvre; this document would then be an anticipation of the Draft Budgetary Plan (DBP) that the Government would subsequently send to the EU by mid-October.

Finally, it would still be possible for the Government to submit to Parliament, pursuant to Article 6 of Law No 243/2012, a report where, in the case of exceptional events, a deviation from the policy objectives would be requested, even if it should be adjusted to the new EU rule framework of rules. Indeed, under the new governance, any deviation due to the occurrence of exceptional events from the initially-agreed expenditure path must be approved by the Council of the EU. Therefore, the above-mentioned Government report to the Parliament should not include a request for authorisation of deviation, but a request allowing the executive to submit to the Council of the EU the authorisation for the deviation from the net primary expenditure path indicated in the MTP.

Considerations on the implications of the new EU framework of fiscal rules on certain aspects of L. 243/2012

The principles of fiscal balance and debt sustainability introduced in the Italian Constitution by the Constitutional Law No 1/2012 have a broad and general value that is in line with the new European economic governance framework.

Instead, the new framework of European rules will require amendments to Law No 243/2012 so to update the principles of fiscal balance and debt sustainability for general governments. In general, a ‘mobile’ referral of the rules to the European law should be strengthened.

Currently, L. 243/2012 stipulates that the fiscal balance is represented by the MTO, or the adjustment path toward the MTO, whose value in based on the criteria established by EU law. The new framework of European rules removes references both to the MTO and to the convergence path of the structural fiscal balance toward the MTO, and this should be reflected in the internal legislation. In the light of the reform, the concept of general government’s balanced budget could refer to the Plan’s public finance objectives which are defined through the trajectory of net primary expenditure funded through national resources. Law No 243/2012 also makes explicit the content of the constitutional principle of debt sustainability through a general reference to EU law, being therefore already in line with the new legislation.

The public finance targets of the Plan will be defined over a five years term horizon legislature and will be binding throughout the period, while the current national economic programming documents cover only a three-year period with the multiannual objectives revised annually. The programming horizon should therefore be extended from three to at least five years.

Finally, the existing legislation concerning the role of the Parliamentary Budget Office already appears to be consistent with the new European fiscal rules framework. Italy has adopted the Two Pack’s requests with Law No 243/2012, which established the PBO and defined its functions. The PBO contributes to the transparency and credibility of the macroeconomic forecasts underlying budgetary planning by assessing and endorsing them, as defined in the Memorandum of Understanding between the MEF and the PBO. In addition to what is already provided for in the existing EU legislation, the new Regulation on the preventive arm calls for a role of IFIs in evaluating public finances during the monitoring phase of the Plan. In the light of the reform, it is possible that the information set allowing PBO to carry out properly ex ante and ex post evaluation and monitoring activities will need to be updated.

Considerations on other aspects of the Italian law

Some procedures are already covered by the regulations in force but, in the light of the new European governance, they should be strengthened or made more transparent. They concern, in particular, the control and monitoring of public accounts and the preparation of forecasts under unchanged policy. As far as budgetary planning is concerned, in some cases the rules already in place should actually be applied.

Multiannual budgetary planning. − In practice, the provisions of Law No 196/2009 concerning the programming of public finance targets have so far been largely disregarded. Law No 196/2009 specifies that the first section of the DEF should include both the multiannual net borrowing targets for the sub-sectors of the general government account related to central government, local governments and social security funds and the manoeuvre needed to achieve the targets by sub-sector, for at least a three-year period. This obligation has always been disregarded. Especially with the new European governance, the planning sequence should include, first, the setting of budget balances and the growth of the general government net primary expenditure indicator under the MTP, together with revenues and expenses; secondly, the allocation of expenditure by sub-sectors and by ministries.

Enriching the information content of the policy documents would increase transparency on priorities of governments’ fiscal policy and strengthen Parliament’s role. The lack of information concerning the current procedures causes many problems; the most important of them is that Parliament, when examining policy documents, has to debate and approve public finance targets with partial information. In particular, this lack of information refers to the sub-sector articulation of fiscal objectives in the DEF and the breakdown of the manoeuvre in revenues and expenses in the NADEF. This makes it difficult to understand the framework of fiscal policy strategic priorities and the overall realism of the proposed strategy in terms of macroeconomic and financial sustainability. For programming purposes, public policy evaluation and expenditure review activities should also be strengthened.

Control and monitoring of public finances. − Annual monitoring of public finances will need to be significantly strengthened; outcomes, data used and assumptions underlying calculations should be made public. In the new context, with net primary expenditure targets set over a multiannual horizon, only exceptionally modifiable and with modest margins of tolerance for possible deviations, the ability to effectively monitor public finance developments during the year is even more important. The data and information contained in the currently published reports should also be reviewed and directed to the need to monitor the net primary expenditure indicator.

Forecast trends. − The new European governance confirms the relevance of the unchanged policy assumption as a criterion for the development of trend forecasts. The role of unchanged policy forecasts, alongside with the current legislation ones, should be strengthened in order to make a more realistic assessment of the size of any corrective action, as well as to make it more comparable with the European Commission’s projections.

The current fiscal rules for local governments and the prospect of European governance reform.

The application of the new European rules to the complex of local authorities is a complicated operation. According to the current regulations, each authority has the obligation to achieve a balanced budget, while compliance with the balance provided for in L. 243/2012, a balance similar to net borrowing relevant for the purposes of the EU fiscal rules, must be established not at the level of individual authority but rather at the level of the whole sub-sector. As a consequence, coordination between the new rules and the accounting rules on budgetary balance should be ensured. On a more substantial level, it will be necessary to ensure that constraints on expenditure dynamics are compatible with the financial needs for carrying out the core functions of local authorities and for providing the essential service performance levels.

In theory, two possible alternative scenarios can be seen for the control of expenditure by local authorities.

The first scenario foresees the maintenance of the current rules based on the borrowing limits of the local authorities as part of the introduction of the monitoring of the spending rule for general government as a whole. This would be feasible if there was no risk that local authorities could increase expenditure significantly by using increases in revenue not attributable to discretionary measures, a risk related to the variability of revenues.

The impact on the expenditure of the cyclical component of local revenues could be sterilised through the periodic review of tax shares and transfers. However, the financing of the core functions and the essential service performance levels will have to be ensured. To this end, it appears appropriate that the Structural Fiscal Plan should define, together with the overall growth rate of net expenditure, also those of the expenditure for key functions and for those where essential service performance levels have been defined. In defining the objectives by sector, the involvement of local authorities must be ensured by recovering the role of the Permanent Conference for the coordination of public finances.

The effectiveness of this approach will depend on the existence of an orderly transfer system and on the ability to correctly predict non-discretionary changes in revenues, in particular non-tax revenue not directly linked to economic activities. As for the first aspect, the implementation of fiscal federalism must be completed by reforming the financing of the Ordinary Statute Regions (OSRs) and rationalising the transfers that still flow to local authorities out of the equalisation funds. If the annual review of the transfers proves to be too complex, an extraordinary fund could be set up, supported by a contribution from local authorities during the positive stages of the economic cycle and distributed to them during the negative stages, by analogy with Article 11 of L. 243/2012 for State participation in adverse phases of the cycle or in case of exceptional events.

The second scenario would foresee the modification of the concept of balanced budget for local authorities in L. 243/2012 by introducing a direct constraint on the growth rate of their expenditure. Monitoring could still be based on the current approach: the State General Accounting would verify ex ante and ex post compliance with the growth rate of the sub-sector expenditure and in case of overruns it could require the necessary adjustments before authorising borrowing. Reliable indicators based on data obtained in a timely manner and not requiring excessive collection and reporting burdens should be identified for this purpose. Consequently, there would be an urgent need to equip local authorities with a single financial and economic accounting system in line with the accounting standards of the international and European general governments (IPSAS/EPSAS) and in implementation of Council Directive 2011/85/EU, as provided for in the reform 1.15 of the NRRP.

Given the high complexity of the budgets and the anticipated evolution of regulations, the possible amendment of L. 243/2012 could be limited to generally defining the indicator to be used for the monitoring of the net expenditure of local authorities, leaving to the ordinary law the task to define any details of its implementation. For municipalities, simplified procedures for smaller institutions should also be considered.

The control of net expenditure would require defining the procedures for the assessment of discretionary changes in local authorities’ revenues and for the collection of related information by the Ministry of Economy and Finance. It would be necessary to clarify whether changes in non-tax revenue, such as, for example, those from tariffs – not linked to changes in rates – and changes in the activity of repression of illegal acts, can be considered discretionary.

Separate attention should be paid to the stock of resources set aside in the Fund for doubtful receivables (Fondo crediti di dubbia esigibilità). Any action aimed at permanently recovering tax evasion or improving the collection capacity of local authorities would free up resources from this Fund, making them, at this stage, usable for new financial commitments.

In both scenarios, the application of monitoring and control mechanisms will have to be ensured to the Special Statute Regions (SSRs), as it already happens today with the balanced budget and, in the future, to the Regions that will access differentiated autonomy. With regard to the latter, the periodic review of the tax shares, provided for in the Government Budget Bill on differentiated autonomy currently being examined by the Chamber of Deputies, must be consistent with the limits on net expenditure growth. As noted in previous hearings, a management of tax-sharing entrusted exclusively to bilateral negotiations within the Joint Committees might not guarantee uniformity of assessments and adequate coordination with the budget planning. Therefore, there is still a need to provide for a single institutional body for coordinated and comprehensive evaluations and decisions, including also the determination of the tax share that, according to Legislative Decree 68/2011, should finance the regional equalisation fund under symmetric federalism.