5 December 2022 | The Chair of the Parliamentary Budget Office (PBO), Lilia Cavallari, spoke today before a joint session of the Budget Committees of the Chamber of Deputies and the Senate. The hearing concerned the preliminary examination of the 2023 Budget Bill and the multi-year budget for 2023-2025. The main elements of the brief delivered to the Committees are outlined below.

Macroeconomic scenario

Gas: prices fall and risk shifts to winter 2023-2024

To address the surge in energy prices, the countries of the European Union have increased their gas stocks, with the filling rate in mid-November reaching 94 per cent, 10 points above the average registered in recent years. This performance, which was facilitated in part by favourable weather conditions, fostered a decline in gas prices from the peaks reached at the end of August. However, any difficulties in replenishing stocks between the spring and summer of next year could create risks for the winter of 2023-2024 in the absence of Russian supplies.

Global economy heads towards stagnation

The outlook for the global economy has deteriorated compared with last summer. According to leading forecasters, the global economy is shifting towards stagnation or contraction between the end of 2022 and the beginning of 2023. This prospect is consistent with the surveys of purchasing managers, which have been signaling a contraction in global output since last August. Overall, since the end of the summer developments in international conditions have been mixed: energy commodity prices have declined, but the slowdown in world trade is holding back economic activity.

Italy slows

In Italy, GDP continued to grow in the summer, thanks to private domestic consumption on the demand side and services on the supply side. However, according to the index developed by the PBO, between July and September the uncertainty of households and firms increased further, returning close to the levels recorded during the sovereign debt crisis of 2012-2013. A number of indicators, including business confidence, are currently pointing to a slowdown in economic activity between the end of this year and the beginning of 2023, mainly because of the war in Ukraine. The carry over GDP growth for 2022 is 3.9 per cent, but the final figure (in the annual national accounts) should be slightly lower because there are three fewer working days this year than in 2021.

According to PBO estimates, in the fourth quarter GDP growth will slow compared with the previous quarter but the overall growth in 2022 will be close to or slightly greater than the Government’s target. Compared with the expectations of institutions and private analysts, the Government’s policy scenario for GDP is acceptable for 2022 but falls at the higher side of forecasts for subsequent years. At the same time, various risks shadow these forecasts, such as developments in the war in Ukraine and a possible resurgence of the pandemic, compounded by the danger that energy inflation and shortages of materials could compromise the implementation of the NRRP.

Inflation approaches peak

Inflation – which Istat preliminary estimates at 11.8 per cent in November – had a heavy impact on the lower-income classes, prompting the previous Government to implement measures to support less well-off households. The 2023 Budget Bill continues this approach through the first quarter of next year, focusing more closely on the neediest households. According to the forecasts of the PBO and other analysts, Italian inflation should peak in the current quarter, while the pace of price increases should slow down next year. However, these are very uncertain projections as geopolitical tensions are driving considerable volatility in commodity prices, which have an impact on the entire supply chain.

GDP: macroeconomic forecasts for 2022-2023 endorsed, but risks remain

The macroeconomic forecast of the recent Draft Budgetary Plan (DBP) has not been changed from that indicated in the revised version of the Update to the Economic and Financial Document (Update), which the PBO endorsed for the 2022-2023 period, albeit underscoring the presence of significant risks.

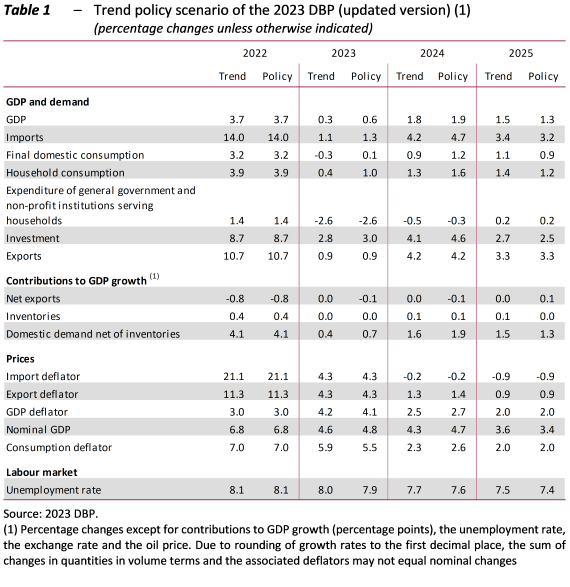

The 2023 DBP scenario incorporates the effects of the budget package, which was assessed by the PBO in early November on the basis of very preliminary information. The budget measures should bring GDP growth in 2023 to 0.6 per cent, three-tenths of a point above the trend scenario. The impact the following year should be just one-tenth of a point of GDP, before becoming slightly negative in 2025 (Table 1). The effect of the budget package on next year’s growth should be concentrated on household consumption, which will benefit from the measures aimed to counter the impact of inflation.

Public finances

The budget package and its financial impact

According to the Technical Reports accompanying the two measures, the public finance package, made up of Decree Law 176/2022 and the 2023 Budget Bill, causes general government net borrowing to increase compared with the trend under current legislation: by 0.5 percentage points of GDP in 2022 (€9.1 billion), 1 percentage point in 2023 (€20.8 billion) and €0.1 points in 2024 (€2.3 billion); in 2025, however, the measures will improve the deficit by 0.2 percentage points of GDP (€4.7 billion).

Compared with the trend scenario, the budget package provides for expansionary measures (i.e. “uses”) equal to 0.5 per cent of GDP this year, 2.3 per cent in 2023, 1.3 per cent in 2024 and 1.1 per cent in 2025. Over the three-year planning period and excluding the measures planned for 2023 to counter high energy prices, uses amount to an annual average of around €26 billion. Resources covering these outlays, equal to 0.1 per cent of GDP in 2022, average 1.3 per cent of GDP in the following three years, being substantially similar (around 26 billion) to uses in 2023 (net of measures to counter high energy costs) and 2024. In 2025, resources (at over €29 billion) exceed uses (equal to about €25 billion), enabling the deficit reduction from the trend forecast programmed for that year.

The budget package entails a reduction in net revenue in each of the four years and an increase in net expenditure in the first two years and a reduction in the second two, above all in 2025. The deficit correction in 2025 relies solely on a reduction in expenditure, especially current spending.

General considerations and possible critical issues

As already noted on the occasion of the recent hearing on the Revised Update, the PBO welcomes the commitment, reaffirmed with the budget package, to reduce the debt/GDP ratio, thanks in part to a planned reduction of the deficit to 3 per cent of GDP in 2025.

The budget package combines measures to counter high energy prices with preliminary economic policy measures, with a view to broader reform measures to be adopted as from 2024. In the case of the revision of the Citizenship Income (CI), an ad hoc fund has been established to finance a comprehensive reform of anti-poverty and active inclusion measures, although funding has been cut by €1 billion. Considering the issues that have characterised the CI instrument since its inception, these measures are to be welcomed. However, partly because the CI constitutes an essential service level (ESL), the abolition of the CI in conjunction with the introduction of a new instrument would have been more appropriate.

For other more structural measures and reforms – which the DBP puts off until the EFD to be published next April –effects will have to be assessed on the equity and efficiency of the tax system, on the fight against tax evasion, on the costs associated with an aging population and, therefore, on the medium-long term sustainability of public finances.

As regards the measures to counter the impact of high energy prices, to which the deterioration in the trend deficit for 2023 is almost entirely attributable, the PBO has already highlighted the risk of having to deploy additional measures, since those included in the budget package only regard the first few months of 2023. The prudent approach adopted so far appears to be acceptable in view of the continuing uncertainty that characterises macroeconomic forecasts and the possibility of European-level agreements to contain the prices of energy products. Looking ahead, given their impact on the public finances and in line with EU guidance, any new measures should be more selective, with a greater focus of aid on the neediest households and firms whose competitiveness has been eroded most severely.

Among measures not intended to counter high energy prices, it is recognised the beginning of a process in which room for manoeuvre will shrink, requiring ever more accurate and prudential quantification of both uses and the resources needed to cover those uses, to avoid greater-than-expected deficit increases, such as those seen recently. This is the case of the “superbonus” building renovation incentive programme, which has been amended with Decree Law 176/2022 to enable more prudent quantification of costs, with the incorporation of more recent information.

The quantification of several measures in the budget package is rather uncertain. This applies both to resources, such as the estimates of the revenue that will be generated by the facilitated settlement of tax disputes, and uses, as in the case of the incremental flat tax for the self-employed. Furthermore, the estimates in the Technical Reports do not quantify the effects that the measures regarding the mechanisms for monitoring, assessing and collecting taxes may have on the level of compliance and thus the level of future revenue. Additional areas of uncertainty concern the revenue effects of the provisions regarding the windfall tax for companies in the energy sector.

Furthermore, Italy’s three-year planning horizon as provided for by Italian legislation makes it impossible to fully consider the effect on the public finances of a series of measures that bring forward tax revenue. Their immediate positive effects are registered but future losses beyond the three-year planning period are only partially recognised.

As regards the measures envisaged in Section II of the Budget Bill, which will produce a reduction in capital expenditure, it is necessary to ensure that the planned rescheduling of the projects – and their concomitant definancing – is consistent with the time schedules for the projects.

From 2024, the need to take account of new appropriations to avoid real reductions in public services delivered by regions and local authorities has been left to subsequent measures to ensure their continuity. Such reductions would not be appropriate, especially in major sectors such as healthcare.

The budget package does not provide resources for the renewal of public employment contracts. It should be recalled that the entire 2022-2024 contractual period and the first year of the subsequent period fall within the three-year planning period covered by the budget package. Such renewals involve significant amounts that will affect the public finances in the short term. It should be considered the opportunity to modify the recent practice of signing all contract renewals in the same year, with the consequent concentration of additional expenditure in a single year.

To ensure that the debt ratio continues to decline, recourse to deficit financing will necessarily have to be limited. Greater attention will therefore have to be paid to the effects of policy measures on economic growth, with particular regard to the implementation of the NRRP and raising resources through the implementation of an appropriate spending review, the fight against tax evasion and the expansion of the tax base.

Finally, the considerable risk factors characterising the macroeconomic scenario must be borne in mind. These represent unknowns that, together with the change in the ECB’s policy stance, which will lead to higher interest rates with a significant impact on servicing the public debt in a situation in which greater recourse is being made to the market, generate significant uncertainties about the evolution of the public finances.

As regards the assessment of the policy scenario in the context of EU recommendations, on 12 July the EU Council adopted its Country Specific Recommendations. For Italy, the EU recommends ensuring a prudent fiscal policy in 2023, in particular by limiting the growth of nationally financed current expenditure below medium-term potential output growth, taking into account temporary and targeted support to counter the impact of energy price hikes and support for Ukraine. The recommendations for 2022 adopted last year also indicated limiting the increase in nationally financed current expenditure.

Preliminary estimates indicate that net nationally financed primary current expenditure grew significantly in 2022, while the EU recommendations called for it to be limited. However, a significant portion of this additional net current expenditure was associated with measures intended to shield users from energy price increases, which the EU has declared it intends to take into account (albeit with regard to 2023). Conversely, developments in the same expenditure aggregate in 2023 would appear to make the stance of fiscal policy more restrictive, conforming with EU recommendations. However, the estimate is influenced by the partial lapse of measures to counter high energy prices.

The main measures in the budget package

Anti-inflation measures for households and firms

The Budget Bill extends and in some cases expands the measures to mitigate the effects of inflation (especially energy). Overall, the measures adopted heretofore for this purpose covering the 2021-2025 period are worth €116.1 billion, of which €28.2 billion in the Budget Bill for 2023. Of the latter, €7.4 billion are directly targeted at households. The measures include an increase in social energy allowances, contribution relief, an increase in minimum pensions and an allowance for the purchase of basic necessities for persons with an ISEE (equivalent economic status indicator) of less than €15,000. A total of €11 billion have been appropriated for firms, of which about 90 per cent is reserved for an extension and increase of tax credits for energy costs. Other measures are directed at supporting the agricultural and sports sectors and to refinance the SME Fund. Some €7.3 billion benefit both categories (households and firms).

Effects of support measures for households

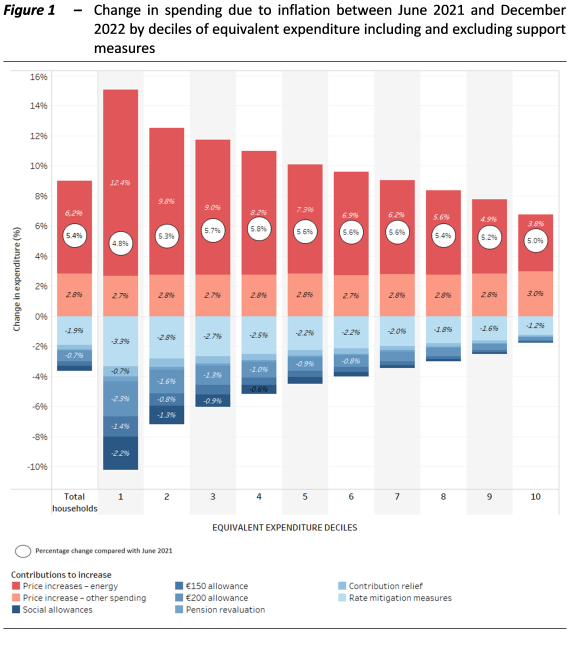

According to a simulation conducted by the PBO (Figure 1), between June 2021 and December 2022 inflation drove up average household spending by 5.4 per cent. In the absence of support policies, however, the impact would have been as great as 9 per cent. Compared with the period June 2021 – September 2022, analysed in PBO Flash no. 2/2022, the effect of inflation increased by around 2.1 percentage points and that of support policies by around 0.4 points, for a net increase of around 1.7 points in the costs of households.

The impact of inflation on the spending of the poorest households (first decile) is around 15 per cent, while it amounts to 6.8 per cent for the richest households (tenth decile). The increase in the focus of support policies on the poorest households helps offset this imbalance, giving a net impact on the first decile of +4.8 per cent in December, which is lower than the average (+5.4 per cent), but still considerably higher than last September (+1.3 per cent).

Given the high degree of uncertainty about price developments, even in the short term, it is a difficult task to assess the effectiveness of the measures deployed to safeguard the purchasing power of households in the coming year. The key variable is energy prices: if they do not cool down in the early months of the new year, new measures could be needed in addition to those financed in the budget package for the first quarter of 2023. Among the main anti-inflation measures, only social allowances and contribution relief for employees are funded for all of 2023. If inflation subsides, it may be necessary to consider a gradual reduction of support measures to avoid causing a sudden deterioration of the financial condition of households and businesses. In both cases, any new interventions by the Government during the year should be more closely targeted at the neediest households and firms and funded adequately in order to avoid unexpected increases in the deficit.

Tax credit for energy costs

The Budget Bill extends and increases the tax credit for companies introduced in 2022 to offset the higher costs of electricity and natural gas until the end of the first quarter of 2023. The Technical Report estimates that these credits will cost the State €9.8 billion, equal to nearly half of the resources already used for the same purpose in 2022 as a whole (about €20.3 billion).

Tax credits can be used to offset tax liabilities or transferred in full to other entities. However, based on the information available as of 22 November, companies used only €2.7 billion of the €4.3 billion expected in the Technical Reports for the first half of 2022 (about 63 per cent) to offset tax liabilities, but this figure could increase with payments expected by the end of the year. Looking forward, the use of tax credits could still be lower than expected because firms could find it difficult to offset the credits (due to insufficient taxable income) or, above all, to transfer them to banks, which are already under pressure from the credits generated by the building renovation incentive programme.

Changes to the flat rate tax mechanism

The budget package raises the revenue ceiling for sole proprietorships and self-employed workers to qualify for the flat-rate tax mechanism (regime forfettario) from €65,000 to €85,000. The Technical Report estimates that, once fully implemented, this change will reduce tax revenue by €404 million per year.

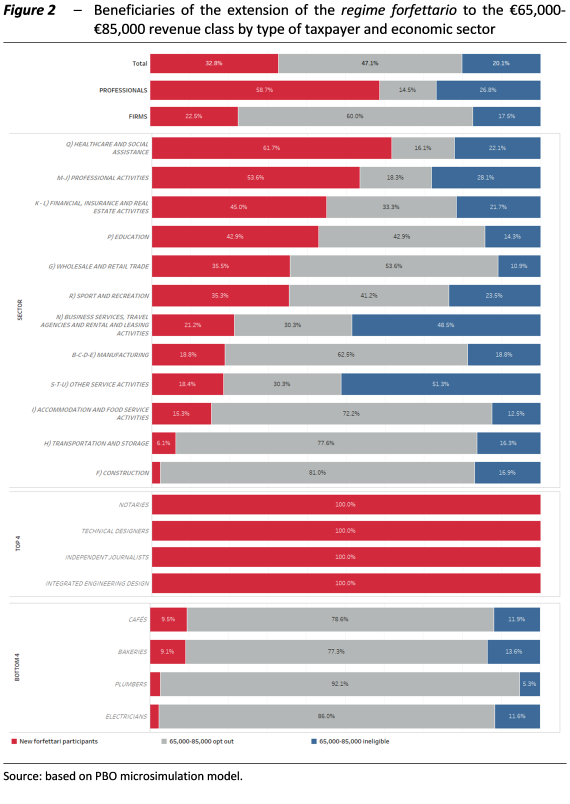

According to PBO simulations, out of approximately 170,000 individuals with revenues of between €65,000 and €85,000 (5 per cent of professionals and sole proprietorships), those who meet all eligibility requirements and would benefit from participating in the flat-rate mechanism number around 60,000. Of the taxpayers in this revenue class, 33 per cent would benefit from participation, 47 per cent will elect to not participate and the remaining 20 per cent do not meet the other eligibility requirements (Figure 2). The participation rate, however, is not at all uniform, being substantially higher among professionals (58.7 per cent) than among firms (22.5 per cent).

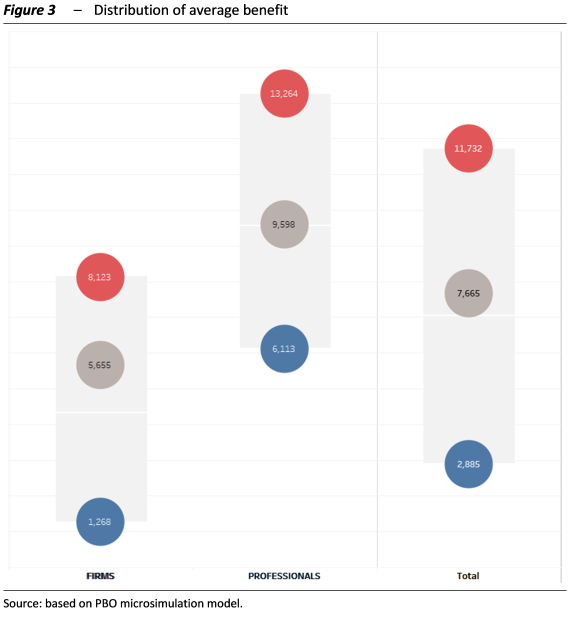

The overall average benefit for new participants in the regime forfettario is about €7,700, of which approximately €5,900 from the transition from ordinary personal income tax (IRPEF) to the flat tax, about €1,050 from the reduction of contributions and about 750 from the exemption from VAT. However, there are significant differences between the categories: professionals gain an average of around €9,600 (and 25 per cent of them obtain a benefit of more than €13,264), while the benefit to firms is just €5,600.

Overall, the extension of the flat-rate mechanism involves a rather limited number of taxpayers, but still raises equity issues within the category of self-employed workers, who are treated differently with no justification based on ability to pay. When income is determined on a flat-rate basis, negligible distortions emerge if the taxpayers involved are small, but these become significant as turnover increases.

Furthermore, the coexistence of the regime forfettario and the ordinary personal income tax system, which continues to apply to employees and pensioners, creates distortions of the principles of horizontal equity.

It should be borne in mind that the implicit criteria involved in the application of the system create a situation in which more than 77 per cent of the participants belong to the 10 per cent of taxpayers with the highest earned income. This means that the additional extension of the regime mainly involves the wealthiest taxpayers. For them, the gain compared with the progressive taxation system is generally very large: half will save more than €7,500 in personal income tax and a quarter more than €9,500.

Finally, raising the ceiling creates a limited incentive to increase revenues, but creates a strong disincentive to growth, since all income becomes subject to ordinary taxation when the threshold is exceeded.

Incremental flat tax

Quantifying the impact of the optional incremental flat tax for recipients of entrepreneurial income and self-employed workers is challenging: on the one hand, it is difficult to predict the increases in self-employment and entrepreneurial income in 2023, considering that previous years were impacted by both the pandemic and the energy crisis; on the other hand, the limitation of the preferential treatment to a single tax period could prompt taxpayers to engage in opportunistic conduct, such as postponing invoices regarding the last few months of 2022 to 2023 or bringing forward invoices for 2024 to 2023.

The application of the mechanism raises the issue of horizontal equity: two taxpayers who earn the same income in 2023 – one increasing the previous year’s income, the other maintaining an unchanged level of income – are taxed differently with no justification based on ability to pay. Furthermore, if we consider two individuals with different incomes that have increased by the same amount, the gain generated by the application of the incremental tax mechanism depends on two factors: on the one hand, the gain of the taxpayer with the higher income tends to be greater when the difference between the personal income tax rate and the rate in lieu of 15 per cent is greater; on the other hand, for an identical increase, the taxpayer with the higher income will have a larger deductible and therefore the difference in rates will be applied to a smaller base, reducing the gain. The redistributive effects are therefore difficult to assess a priori.

In efficiency terms, the measure is limited to only one tax year and is therefore unlikely to provide a structural incentive for economic activity or the reporting of income hidden from the tax authorities.

Windfall profits tax for the energy industry

The budget package also introduces two new temporary taxes on the energy industry, both in implementation of Regulation (EU) 2022/1854, with the goal of redistributing the surplus profits that the sector has earned as a result of the significant increase in prices:

- a tax of the revenues of electricity generators that exceed a certain ceiling (from 1 December 2022 to 30 June 2023);

- a solidarity contribution for 2023, similar to a surtax on the share of profits that exceeds the average of the previous four years.

The first tax extends the ceiling introduced with Decree Law 4/2022 as amended by the third Aid Decree (Decree Law 144/2022) for companies producing electricity from renewable sources to all electricity generators.

The second tax is paid in addition to and partially overlaps the tax base of the windfall tax introduced with Decree Law 21/2022 and then amended with the Aid Decree (50/2022).

The new taxation of energy companies is justified by revenue needs and redistributive purposes (explicitly referred to in the EU Regulation), but appears highly complex and unclear in certain respects, which makes it difficult to assess its actual impact. In 2022 and 2023, most energy companies could be subject to three extraordinary levies (the tax based on revenues, that based on value added and that on surplus profits) that differ considerably in terms of time periods, tax bases and effective rates.

Citizenship Income

The Budget Bill also amends the Citizenship Income (CI) programme, restrictively modifying the rules that govern eligibility for 2023 and repealing the scheme from 1 January 2024, in view of a comprehensive reform of anti-poverty and active inclusion measures, whose salient features are currently unknown.

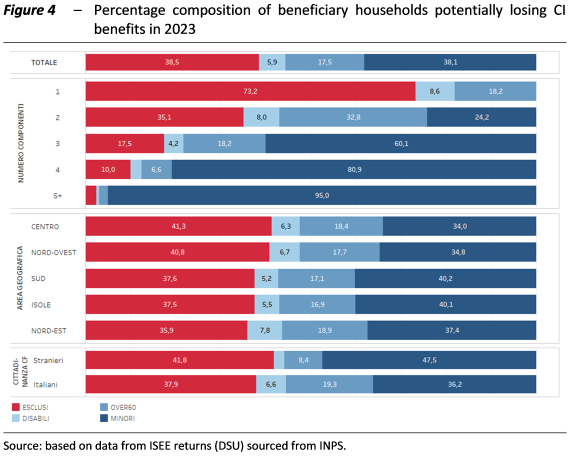

More specifically, in 2023 the current benefit will be paid for the entire year to all households with disabled persons, minors or people aged 60 or over and for eight months to all others. The population of households in poverty to be supported is therefore implicitly redefined, with eligibility being linked not only to income level but also to the presence of disabled beneficiaries or specific age conditions (under 18 and over 60). According to the Technical Report, the measure generates cost savings of €785 million in 2023 (which become €776 million following the automatic increase in the universal allowance for dependent children).

From 2024, the abolition of the CI will produce savings of just over €8 billion a year (again net of the increase in the single allowance), of which around €7 billion will go into the new Fund to support anti-poverty and labor inclusion programmes established in the budget of the Ministry of Labour and Social Policies, pending a comprehensive reform of the programme.

A number of critical issues have arisen since the introduction of the CI, particularly with regard to support for those who are unable to find a place in the labour market. The plans for a comprehensive reform are consistent with the broad debate on the need for corrective measures to render the programme more effective in both countering poverty and supporting those who cannot find a job. However, partly in light of the fact that the CI constitutes an essential service level (ESL), the abolition of the CI in conjunction with the introduction of a new programme would have been more appropriate.

A PBO simulation based on INPS data shows that under the new rules introduced with the budget package, 38.5 per cent of households that today receive the CI could lose it from August 2023 (Figure 4).

Those who will no longer receive CI benefits after August include three-quarters of single-person households, while the share of those excluded decreases as the number of household members increases (essentially due to the presence of minors).

The share of persons no longer eligible is substantially constant within geographical areas, with slightly higher percentages in the Centre and the North-west (41.3 and 40.8 per cent respectively). Given that most beneficiaries of the CI live in the South, it follows that most of those excluded will reside in that area.

With regard to nationality, foreigners are more affected by the amendment (41.8 per cent no longer eligible) than Italians (37.9 per cent), reflecting a smaller presence of disabled people within their households.

Considering individual beneficiaries instead of households, the analysis shows that only 22.9 per cent of individuals will lose the CI, with a slight prevalence of men (25.2 per cent) over women (20.7 per cent), who are more protected, primarily due to the presence of children.

With regard to employment status, 36.1 per cent of the unemployed and less than a third of the employed will be excluded. The latter are individuals with very low incomes (the working poor), who should be taken into account when redesigning anti-poverty and active inclusion programmes.

Pensions – Quota 103

According to PBO estimates, if all those eligible to participate in the Quota 103 early retirement mechanism do so, the increase in the number of pensions being paid at the end of the year will be over 56,400 in 2023, around 40,800 in 2024 and just under 6,400 in 2025. Quota 103 participants would be primarily men (about 85 per cent) and just over 13 per cent would come from the public sector. In the private sector, about 65 per cent would be payroll employees, just under 24 per cent would be self employed and the remainder would be para-employees, enrolled in separate pension funds and show business workers (formerly the ENPALS pension fund). In 2023 and 2024, Quota 103 pensions would average around €27,400 and €28,800 gross per year for men and about €22,400 and €24,100 for women. Using these figures, the Quota 103 programme would cost, gross of taxes, about €0.6 billion in 2023, just under €1.4 billion in 2024 and about €0.5 billion in 2025, before producing a decrease in expenditure of just over €0.1 billion in 2026.

If participation were instead similar to that for the Quota 100 programme in the 2019-2021 period, the number of additional pensions would be equal to just over 29,700 in 2023, just over 26,000 in 2024 and around 2,900 in 2025. Quota 103 would cost around €0.3 billion in 2023, just over €0.8 billion in 2024 and around €0.4 billion in 2025, with a decline of around €0.05 billion in expenditure in 2026.

The cost estimates contained in the Technical Report accompanying the budget package (€0.451 billion in 2023, €1.219 billion in 2024, €0.476 billion in 2025) can therefore be considered conservative.

Pensions –An incentive to continue working

Anyone who meets the Quota 103 requirements by 2023 but chooses not to retire early will be able to request that their share of contributions (just over 9 per cent of their gross remuneration) not be paid by their employer to INPS but rather paid directly to them in their paycheque. The measure, providing an incentive not to leave retire before meeting the ordinary seniority or old age pension requirements, is modelled on the so-called “Maroni bonus” of 2004, which, however, was more beneficial for three reasons:

- at that time, pension requirements were much lower, so the measure was aimed at younger workers, for whom it was less burdensome to continue working;

- both the contributions paid by workers and those paid by employers were paid directly to workers in their paycheque;

- the pensions of the workers involved were calculated in full on a defined benefit basis, which made early retirement an attractive option.

The new early retirement incentive programme might therefore not be particularly attractive, except for those who have an immediate need for liquidity. The Technical Report estimates that the preferential programme will be taken up by just 6,500 individuals, i.e. less than 10 per cent those who, according to PBO estimates based on INPS data, will still be working next year despite having met the requirements to retire under one of three Quota programmes (Quota 100, Quota 102 and Quota 103).

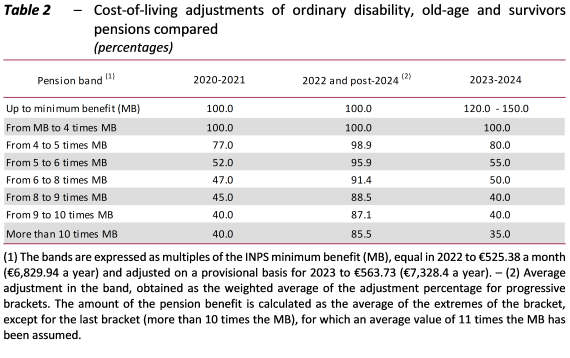

Pensions – Changes to the cost-of-living adjustment mechanism in 2023-2024

The budget package amends the rules governing the cost-of-living adjustment of pensions for the 2023-2024 period and uses the resulting savings to fund other measures. The new rules provide for a “band-based” mechanism similar to that adopted in 2020-2021 in place of the “bracket-based” mechanism that was reintroduced in 2022. In the former, the entire pension is revalued using a single percentage, which varies depending on the amount of the pension. In the latter case, different percentages are applied to the different amount brackets within the same pension, using a mechanism similar to that envisaged for personal income tax (IRPEF).

With regard to the cost of the measure, the Technical Report estimates have been confirmed: in 2023, with inflation at 7.3 per cent, the change will reduce expenditure, net of tax effects, by over €2.1 billion, while in 2024, with inflation at 5.9 per cent, savings amount to just under €4.1 billion.

Furthermore, for the next two years, pensions (ordinary disability, old-age and survivors pensions, social allowances and civil disability allowances) smaller than the minimum pension will also be granted a one-off supplement to the indexation adjustment which will cost €210 million in 2023 and €379 million in 2024.

In general, the mechanism for 2023-2024 is much less favourable than that in place in 2022, especially for pensions exceeding five times the minimum (Table 2).

Compared with people of working age, pensioners are much more vulnerable to inflation, and therefore maintaining their purchasing power is entrusted almost exclusively to the cost-of-living adjustment mechanism. For the portion of pensions calculated using defined-contribution rules (which will grow over time), any slowdown or freeze (even temporary) of the adjustment must be considered as a tax. If the regular annual cost-of-living adjustment is weakened, pensioners will eventually receive less than they are entitled. The revaluation rules should therefore remain as stable as possible.

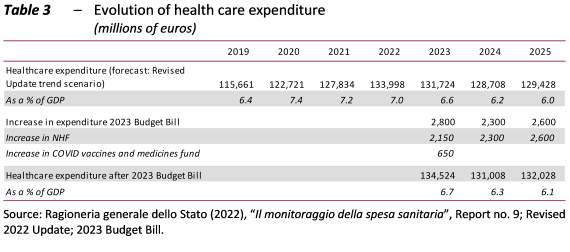

Healthcare

Despite the increase in funding for the National Health Service (NHS) (€2.15 billion for 2023, €2.3 billion for 2024 and €2.6 billion from 2025), an expansion of the healthcare system does not seem to be envisaged over the financial planning horizon. Planned healthcare expenditure, which has been estimated by supplementing the trend forecasts contained in the Revised Update 4 November 2022, with increases equal to the greater funding granted (assuming that it is fully used), declines to 6.1 per cent of GDP in 2025, which is even lower than in the pre-pandemic period (6.4 per cent in 2019, compared with an EU average of 7.9 per cent).

As already noted by the PBO in the past, the pandemic has helped aggravate certain problems faced by the NHS, in particular a shortage of personnel, which today is becoming a national emergency (the problem mainly involves nurses and certain categories of physician, including anesthesiologists and emergency-care specialists). The condition of emergency services is barely sustainable. In the case of physicians, remuneration has not been adjusted over time and the specific allowance for emergency services has still not been paid, while forms of employment other than payroll employment are spreading, mediated by cooperatives, with an increase in costs and an adverse impact on the organisation of services. The extension of the regime forfettario for self-employed workers envisaged in the budget package could encourage medical professionals to opt for self-employment in the private sector.

Faced with this situation, the lack of guidance on public employment contracts and the fact that the increase in the emergency services allowance will only be granted from 2024 do not enhance the attractiveness of the NHS, while COVID-19 is still under way and efforts are being made to reduce waiting lists for other procedures created as a result of the health emergency, the implementation of the new essential care standards determined in 2017 is not yet complete and NRRP investments will require an increase, albeit progressive, in spending to manage the new services. New interventions may be necessary, even during 2023.

Essential Service Levels (ESLs)

Primarily for the purposes of the full implementation of Article 116 of the Constitution, which provides for the possible attribution of additional forms and conditions of local autonomy, the Budget Bill outlines a procedure for the rapid determination of the essential levels of services concerning civil and social rights that must be guaranteed throughout the national territory (ESLs) as a mandatory element of the implementation of differentiated or asymmetrical autonomy.

As part of the long process of implementation of the Title V reform, the symmetrical fiscal federalism envisaged by Legislative Decree 68/2011 has not yet been implemented, while the application of the municipal equalisation mechanism has been hampered by the lack of ESLs. The Budget Bill appears to give priority to the implementation of asymmetric federalism, and it is not clear how this, given such priority, should be reconciled with the symmetrical federalism envisaged under Article 119 of the Constitution.

The provisions set out in the budget package accelerate the determination of the ESLs, but priority is ensured only for the areas that fall within the reform project for differentiated autonomy. Civil and social rights therefore appear to play an ancillary role with respect to the objective of granting further autonomy to the regions.

The proposed legislation seems to echo the provisions of Legislative Decree 68/2011 regarding the methods for defining ESLs and Legislative Decree 216/2010 for the determination of costs and standard needs, but differs radically for the absence of a provision aimed to define a path of convergence of the service objectives to the ESLs, to be determined by law. So the whole operation seems to be limited to systematising the existing situation, assuming as ESLs the services that are already envisaged by the legislation or in any case are offered on the territory and re-evaluating the expenditure in terms of cost and standard needs. There is no clear distinction between the technical sphere, which concerns the recognition of the existing, and the eminently political choice of fixing the ESLs.

Furthermore, it does not appear that any mechanism is envisaged to overcome territorial gaps, as the ESLs relating to services that have not already been provided cannot be determined – let alone financed. The evaluation of the resources to be transferred to the Regions that will ask for new spaces of autonomy would therefore take place on the basis of a snapshot of the current situation.

Among other things, it is not clarified how the ESLs regulation introduced can be harmonized with other provisions which envisage a path of convergence, in particular with the rebalancing process in the offer of services for children envisaged by the budget law of the last year and by the NRRP.

Tax collection

The maneuver introduces highly facilitative measures with reference to both the moment of control and litigation, and that of enforced collection. The first measures include the regularisation, definition, adhesion and conciliation of tax assessments and disputes. In the matter of enforced collection, novelties are introduced in terms of loads entrusted to the collection agent and in the matter of uncollectable notices. On the one hand, it allows taxpayers to better deal with any liquidity crises connected with the continuation of the inflationary period triggered by the increase in energy prices. On the other hand, it allows the collection agent to better manage bad debts. According to estimates, these measures will reduce tax revenues by 1.1 billion in 2023 and increase them by 0.9 and 0.7 billion in 2024 and 2025.

Provisions of this nature have already been approved in past years and introduce elements, even temporary ones, which should be better placed within an organic reform of the tax assessment procedures, the penalty regime, the collection and management of the residual debts. Their repetition – in the absence of an overall plan aimed at providing for, among other things, the introduction of mechanisms for the automatic cancellation of uncollectable debts, with the aim of reducing the stock of folders – in fact risks damaging both the efficiency of the collection system and the relationship with taxpayers, who could be induced not to pay taxes pending future amnesties.

Furthermore, non-strict policies in the fight against evasion risk jeopardizing the achievement of some objectives set by the NRRP. On the basis of the commitments undertaken with the Plan, in fact, in 2023 and 2024 the propensity to evade must be lower, respectively, by 5 and 15 per cent compared to 2019.

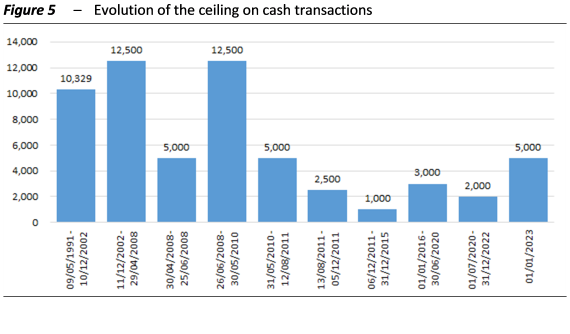

Cash ceiling

In contrast to the trend in recent years, the maneuver raises the ceiling on cash transactions from 1,000 to 5,000 euros (fig. 5) and introduces a limit under which merchants can refuse to accept POS payments without incurring penalties (60 euros). Therefore, mechanisms that generally support and provide assistance to the tools to combat tax evasion (split payment, electronic invoicing, electronic sending of receipts) and money laundering are modified, in a less restrictive sense.

Limits on the use of cash are present in 14 out of 27 countries of the European Union, with thresholds ranging from a minimum of 500 euros in Greece to a maximum of 15,000 euros in Slovakia.

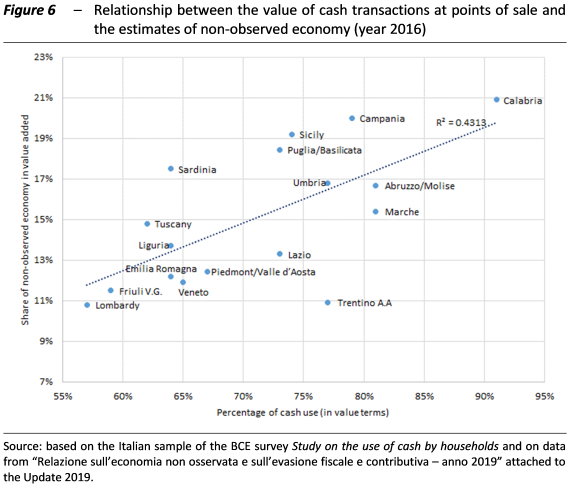

The economic literature is almost unanimous in maintaining that the increase in cash payments can lead to an increase in tax evasion. Figure 6 shows that the Italian regions where the use of cash is more widespread are also those where the highest levels of VAT evasion are estimated.

Measures to limit the use of cash could play a positive role in the fight against evasion and money laundering. A study by Giammatteo et al. (2022) shows that the increase in the cash ceiling introduced with the 2016 maneuver (from 1,000 to 3,000 euros) had the side effect of making the underground economy grow. An analysis by Russo (2022) concludes instead that the reduction adopted at the end of 2011 (from 5,000 to 1,000 euros) helped to bring down evasion, especially in sectors where the propensity to evade is higher.